|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Bruce Alderman, M.A., .is adjunct faculty in the John F Kennedy School of Psychology at National University. He received his master's degree in Integral Psychology, with an emphasis on Transpersonal Counseling Psychology, from JFKU in 2005. He has published essays in the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice and Consciousness journal, as well as in several anthologies on Integral philosophy and spirituality. Recently, he contributed to and co-edited the January 2019 special issue of Integral Review journal on Integral Postmetaphysical Spirituality. Faculty Profile. Email: [email protected]

Bruce Alderman, M.A., .is adjunct faculty in the John F Kennedy School of Psychology at National University. He received his master's degree in Integral Psychology, with an emphasis on Transpersonal Counseling Psychology, from JFKU in 2005. He has published essays in the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice and Consciousness journal, as well as in several anthologies on Integral philosophy and spirituality. Recently, he contributed to and co-edited the January 2019 special issue of Integral Review journal on Integral Postmetaphysical Spirituality. Faculty Profile. Email: [email protected]

Integral Religious PluralismA metaRealist InflectionBruce AldermanI wrote this paper on integral religious pluralism over five years ago, and have not shared it publicly because I expected it to be published in an anthology, but I think that project may be indefinitely on the back-burner so I've decided to share it here. In it, I attempt an interface between Wilber's integral postmetaphysics, Bhaskar's critical realism, and Ferrer's participatory metaphysics.

The issue between Integral Theory and Critical Realism, then, is not so much that Integral Theory lacks grounding in ontology, but whether its ontology is an adequate or coherent one.

A central aim of Ken Wilber's (2006) Integral Spirituality, and more generally of the postmetaphysical turn in Integral Theory, is to re-legitimize religion—religious experiences and worlds—in contemporary intellectual culture. As Wallace (2000) and Wilber (1998, 2006), among others, have pointed out, religious traditions have not fared very well under the exacting gazes of science and the humanities; they have lost credibility as generative sources of knowledge or emancipation in their own right. However, contrary to Wallace's (2000) contention that religion, particularly in its contemplative dimensions, has been sidelined in modern culture due to the materialist taboo on subjectivity, Wilber (2006) maintains that the greatest challenge to religion in our time is posed by the postmodern, intersubjectivist critique of empiricism and phenomenology (as monological and perpetuating the myth of the subject). The various attempts in transpersonal psychology, Western Buddhism, and the New Age to re-legitimize religion as 'contemplative science'—in effect, by casting spirituality as a form of inner or mystical empiricism—have thus fallen short of the mark and have failed to gain traction in the academic world, largely because they have missed this broader postmodern critique. In Integral Spirituality, Wilber (2006) demonstrates how a postmetaphysical, meta-theoretical approach to these issues allows us to include both the strengths of a 'broad empiricism'—which includes inner as well as outer methods of trained observation—and the critical insights of postmodernity into the contextuality and constructedness of the subject and its experiences. With this move, Wilber aims to offer an integrative metatheory of religion and spirituality which redeems the empirical reality (and transformative potential) of mystical states and experiences, while also acknowledging the situated, enactive nature of spiritual phenomena. I do not intend to review the details of Wilber's model in this chapter; I mention these points here only to highlight one of the central questions I plan to address in the coming pages: whether Wilber's articulation of a postmetaphysical, enactive approach succeeds in its attempts to preserve the dignity and ontological weight of spiritual phenomena, and to account for their plurality, without sliding either into naïve metaphysics or inert, postmodern relativism. As I discuss below, while I believe Wilber's model does go a long way towards achieving these aims, and to demonstrating the continuing relevance and emancipatory potential of religion in our time, an underdeveloped ontology prevents it from fully doing so. I will turn to Roy Bhaskar's work for help in clarifying and dealing with these issues.  Roy Bhaskar (1944-2014) In two previous papers (Alderman 2011, 2012), I attempted to develop an integral, post-metaphysical model of religious pluralism and trans-lineage spiritual practice by situating Wilber's Integral model alongside, and bringing it into generative dialogue with, several other contemporary approaches, including Jorge Ferrer's participatory metaphysics, Raimon Panikkar's cosmotheandric theology, and the work of several Polydox theologians. In this chapter, I will continue this project by bringing Wilber's approach into conversation with Roy Bhaskar's Critical Realism and metaReality. My intention for doing so is three-fold:

To facilitate the first part of this exploration, after a brief review of the ground covered in previous papers, I will attempt a response to Wilber's (2012a) "Response to Critical Realism in Defense of Integral Theory," particularly to identify and address several points of terminological and conceptual confusion—which, if left unaddressed, are likely to impede further fruitful contact and communication between these two approaches. More specifically, I am interested in looking at how certain key insights from Critical Realism and metaReality can be used to amend, deepen, and re-contextualize, rather than supplant, Wilber's model of integral participatory enaction. With these points established, I would then like to do a comparative review of Integral postmetaphysical, participatory, and metaRealist models of interreligious relationship and dialogue, and to consider in particular how Critical Realist and metaRealist perspectives might inform or contribute to the development of a more ontologically robust model of Integral religious pluralism. In "Kingdom Come" (Alderman, 2011), my first paper on this topic, I drew on David Ray Griffin's (2005) distinctions between identist and differential forms of religious pluralism to argue for an Integral version of the latter—an Integral differential pluralism—on enactive or participatory grounds. Identist pluralism, most commonly associated with the neo-Kantian theology of John Hick, contends that all authentic religious traditions are in touch with the same, ultimately unknowable Reality, and that all involve and variously enable the same essential spiritual transformation: moving from self-centeredness to Reality-centeredness. The source of religious differences across (and within) traditions, according to this view, is found in various mediating cultural and linguistic factors. Convention may lead believers to describe the absolute in personal or impersonal terms, for instance, but all such descriptions equally fail: the noumenal Reality which grounds all religious traditions is in itself utterly unknowable and inconceivable. While clearly advocating for the ultimate unity of the world's religions, the identist approach is considered pluralist because it grants equal validity to multiple religious traditions, as opposed to religious exclusivism, which considers only one tradition authentic; or religious inclusivism, which allows for the validity of other traditions only to the extent that they (imperfectly) participate in and reflect the primary tradition's truths. By contrast, differential pluralism holds that ultimate reality itself is ontologically differentiated, allowing for real rather than merely interpretive differences among religions: theistic and nontheistic traditions, for instance, are in this view each encountering and exploring distinct dimensions or aspects of the Real. In granting the ontological differentiation of the absolute, differential pluralism also opens the way for a plurality of "salvations" (Heim, 1995) or soteriological ends, as the realization mediated by communion with one particular aspect or dimension of the sacred is potentially quite different in flavor or expression from realization mediated by a different aspect. Thus, from a differential pluralist perspective, identist pluralism is not really pluralistic enough. The differences it allows are merely human conventions or projections. They are surface distortions on the face of an inscrutable darkness—an absolute Other, which, in its utter inaccessibility, renders each tradition that orients towards it and attempts to describe it, not partially right, but equally wrong (Griffin, 2005). Differential pluralism resists this essentially Kantian move and advocates instead for a more robust spiritual ontology. Integral postmetaphysical and participatory models follow differential pluralism in embracing multiple, ontologically differentiated spiritual objects or realms, but they conceive of these objects as participatorily enacted or co-created spiritual realities, not self-existing elements of a pre-formatted metaphysical whole. In this way, integral postmetaphysical and participatory approaches aim to avoid the myth of the given, which is the belief that the world we experience as given to us in consciousness is the world as it is in itself, rather than as uniquely mediated and enacted by embodied, historically, intersubjectively, and developmentally situated individuals. To focus for now on the integral postmetaphysical approach (I will return to a discussion of Ferrer's participatory model in a subsequent section): In Integral Spirituality, Wilber (2006) attempts to sidestep the myth of the given by asserting the fundamental priority of person-perspectives, arguing that "each thing is a perspective before it is anything else" (p. 253). By this, he means that, whatever else we might say that something metaphysically is—whether a feeling, a perception, a spiritual or material object or process, etc.—it is first, or already, a first-, second-, or third-person perspective. Every object is an object-for, an appearance for some perceiver. This entails that there is no pregiven, self-existing world independent of all perspective or perception; there are only enactively emergent perspectival occasions or sentient beings.

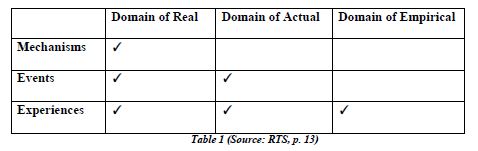

For readers who have followed the initial discussions between Critical Realists and Integral Theorists[1], you might expect the Critical Realist at this point to raise her hand in objection, cautioning against the epistemic fallacy (which is the error of reducing the being of things to our knowledge of or access to beings; or, more generally, reducing ontological questions to epistemological ones). I have addressed this question in a previous paper (Alderman, 2012), prior to Wilber's (2012a) published response to Critical Realism; but given a number of the arguments that Wilber makes in that response—which, to me, suggest a clear misapprehension of key Critical Realist and metaRealist perspectives, including the concept of the epistemic fallacy—I believe a careful review of Wilber's contribution to that discussion is merited. At the heart of the current disagreements between Integral Theory (IT) and Critical Realism (CR) is the question of the nature of ontology and its relationship to epistemology. Does Critical Realism enshrine, at its base, a fundamentally fragmented model of being, as Wilber contends? Does Wilber, in his postmetaphysical effort to avoid the myth of the given, fall prey to the epistemic fallacy? Other authors besides me have explored some of these questions elsewhere (Hedlund, 2015; Marshall, 2015), and I do not intend to rehearse all of the arguments here, but I do believe it will be instructive to use Wilber's recent response to Critical Realism to highlight, and critically reflect upon, the fundamental points of contention that currently divide these two approaches. In particular, I would like to look at Wilber's (2012a) framing of the issues and his major criticisms of Critical Realism, most of which suffer, in my view, from an incomplete or incorrect understanding of Critical and metaRealist principles. I will offer an alternative framing of the issues and will attempt to demonstrate the relevance of important Critical and metaRealist concepts even within a panpsychic, Integral reality frame. With that work done, we can then turn to the more constructive effort of exploring possible metaRealist contributions to an Integral theory of religious pluralism. On Wilber's Response to Critical RealismAt the time of this writing, Wilber's (2012a, 2012b) most in-depth reflections on Critical Realism (CR) come in the form of several pre-released endnotes from his forthcoming book, Sex, Karma, and Creativity, published as a single essay in the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, and in a brief follow-up essay available as a resource paper on the MetaIntegral website[2]. In these articles, Wilber outlines four or five significant differences between Integral Theory (IT) and CR that he perceives, and offers a defense of IT against the charge that it commits the epistemic fallacy. These writings contain few citations or references, however, so it is difficult to tell whether Wilber has read any of Bhaskar's major works, or if he is possibly relying on written summaries of his work by others[3]. One of Wilber's (2012a) main criticisms of CR, which he mentions multiple times, is that it splits epistemology off from ontology and designates ontology alone as the province of the real. What Wilber means by this is clarified by several additional, dramatically worded claims that CR "sucks" or "rips" consciousness out of the Kosmos and leaves only a dead, insentient beingness or ontology as the foundational element of its worldview. To open my dialogical engagement with Wilber's essay, I will first respond directly to this charge itself, and then will take a step back to look at the particular terms Wilber uses to frame this debate. Briefly, and most simply, it is a mistake to interpret CR's notion of the real through the modernist lens of eliminative materialism. In CR's stratified ontology, the terms empirical, actual, and real refer to three increasingly encompassing domains (Bhaskar, 1975/2008). This is best illustrated through the table below.  As this illustration should make clear, the domain of the real is the most inclusive of the three, transcending and including the actual and empirical domains. As such, it encompasses not only generative mechanisms or causal laws, but also actual events or processes, and conscious experiences or perceptions. Mechanisms are shown as exclusive to the domain of the real because, while real, they are frequently unactualized or out of phase with manifest events, and are withdrawn from empirical access (and thus typically excluded from empiricist accounts of reality, which restrict their focus only to what is given in experience). Because mechanisms are exclusive to the domain of the real, the "real" is sometimes used as a shorthand term for mechanisms alone (which is a possible source of Wilber's misapprehension of this issue). But, again, it would be a mistake to interpret mechanisms through an eliminative materialist lens, since mechanisms are also stratified and structure or inform not only the physical, but the biological, psychological, and social levels of existence as well (Collier, 1994). More on this topic will be said as we proceed, but this simple illustration should be enough to dispatch with the notion that Bhaskar's concept of ontology or "the real" is limited to a consciousness-free, "denuded" stratum of being. It aims rather for a richly stratified, maximally inclusive ontology, granting equal reality to unmanifest causal laws or structures, manifest actual processes or events, and conscious/experiential dimensions of being (which Bhaskar (2002a) divides minimally into unconscious, subconscious, vital/emotional, mental, and supramental layers). In speculating on Wilber's source material above, I was suggesting that Wilber's limited interpretation of CR's concept of the real might be due to lack of familiarity with Bhaskar's fuller corpus; but it might also be attributable to Wilber's seemingly idiosyncratic interpretation and use of the terms ontology and epistemology, so I would like to take a moment to examine this usage below, and to offer some hopefully clarifying distinctions. To begin, let's look at a few illustrative quotes from Wilber's (2012a) essay:

While Wilber occasionally uses epistemology and ontology in their more formal senses to refer to distinctive philosophical disciplines, the quotes above make it clear that he frequently uses them synonymously with consciousness and being (with the latter referring, evidently, to strictly non-conscious thingness, is-ness, or matter). With this looser or more colloquial definition of the terms in force, it is clear why Wilber might read CR's association of ontology with the domain of the real as a variation on the materialist reduction of reality itself to "insentient stuff." But this is a highly misleading use of these concepts, unfortunately, particularly for coming to terms with CR's revaluation of ontology as a philosophical discipline and its related critique of the epistemic fallacy. Ontology is the branch of metaphysics[4] concerned with the study of the nature of being or reality. As such, it is not limited to one metaphysical view (such as materialism), but rather encompasses multiple metaphysical orientations, including idealist, materialist, dualist, and nondual-panpsychic worldviews. Consciousness and matter, considered as real aspects or components of being, are equally valid ontological domains of concern. Therefore, Wilber's (2012a) insistence that epistemology and ontology, here defined as consciousness and being, cannot be separated from each other—because they are equally real and "go all the way down"—is fundamentally an ontological argument. Epistemology, by contrast, is concerned with questions of how we know; it is the philosophical investigation into the nature, scope, and limits of knowledge. As such, it constitutes its own distinct domain of inquiry, even if we hold (ontologically or metaphysically) that consciousness and being/matter are co-arising and inseparable. Thus, to argue that ontology and epistemology—as philosophical disciplines which investigate, respectively, what beings are and how we know—should not be problematically conflated and should be granted their own dignity as distinct, if related, domains of inquiry, is not to insist that being is "more real" than consciousness. That would be an ontological argument; whereas, CR's setting of philosophical disciplinary boundaries is more akin to Wilber's epistemological heuristic principle of non-exclusion: freeing disciplines by limiting them (even if we hold, as IT does, that they also co-arise). To unpack this, and to better explore CR's concepts of the real and the epistemic fallacy, I believe it will be useful to bring in some distinctions that Joel Morrison (2007), an integrally informed philosopher and metatheorist, introduces in SpinbitZ, his major philosophical work to date. Specifically, Morrison offers a way to think about, and visualize, twin (intersecting and co-implicating) polarities: the horizontal (x-axis) polarity of ontology and epistemology, and the vertical (y-axis) polarity of the ontic and epistemic.

Figure 1. Ontic-epistemic polarity. From Morrison (2007); used with permission.

As the figure above illustrates, these terms can be applied self-referentially to each other—using the classic Taoist yin/yang symbol—to illuminate both the epistemic nature of ontology (and epistemology) (they are both knowledge disciplines), and the ontic nature of ontology (and epistemology) (they are both real modes of knowing). The relation of these terms to each other can be most easily understood, as Morrison (2007) points out, by recalling "that 'ology' itself refers to a field of study, or knowledge, the real world of the epistemic, and that the 'ic' points out a real aspect or feature of reality [i.e., ontic]" (p. 552). In other words, ontology and epistemology are relative forms of knowledge, or polar distinctions drawn within the real domain of the epistemic, while the epistemic and ontic domains are polar aspects of the real, the former transcending and including the latter (since knowing is both hermeneutic and real, regardless of its domain of focus or its representational clarity or acumen). How might these distinctions be understood in a Critical Realist context? As I discussed at the beginning of this section, CR includes knowing/experience within its domain of the real (similar to Morrison above). Morrison's (2007) vertical arrangement of the ontic and epistemic can be read as illustrating the CR claim that the real, while it includes experience, cannot be reduced to experience or to what is presently known: the real always exceeds what is given in awareness (although experience itself is real and is a constitutive aspect of the real). This does not amount to the (materialist) claim, in other words, that "real being" consists of wholly non-conscious or interiorless stuff. Rather, it is the assertion that our experience of a being does not exhaust or wholly determine the reality or being of that being. Whatever a being is, at any level of existence, it simultaneously makes itself available for and mysteriously eludes epistemic access. This is the simple (and ethical, Levinasian) claim that the reality of a being should not be confused with or reduced to its immediate givenness to consciousness or presence. In CR terms, this is because beings are understood as complex, open systems, with multiple overlapping and mutually reinforcing or interfering "levels," and therefore the phenomenal appearance of a being to inspecting consciousness may be, and often is, out of phase with both its full actuality at any given moment, as well as its unactualized but nevertheless real generative power or potential.

Similarly, Morrison's (2007) horizontal arrangement of epistemology and ontology suggests, in a CR reading, that they are equally real, valid, and even correlative or co-arising, but nevertheless irreducible, domains of knowledge or inquiry. This point has bearing on the CR critique of the epistemic fallacy. As Bhaskar (2002a) writes, "Once you situate ontology as an independent subject then it is always possible that not only will some claims to knowledge be incorrect, but there will be far more to being than current knowledge ever imagines" (p. 286). The epistemic fallacy arises when epistemology is over-privileged (i.e., when ontology is either subordinated to epistemology, or rejected altogether as a valid field of philosophical reflection), as you sometimes find in post-Kantian, postmodern contexts; or when the being of things is regarded as identical to, or somehow dependent upon, our mode of access to them. Critical Realism accepts the idea that, at the transitive domain, we partly construct and translate the objects of our perception, as Kantians and post-modern philosophers maintain. But it rejects the frequently accompanying correlationist claims that 1) objects are nothing more than, or at least cannot be meaningfully discussed as anything but, human constructions; 2) that serious ontological reflection is therefore fundamentally naïve; and 3) that the locus of discussion should thus be shifted to the fields of linguistics, sociology, psychology, or other non-philosophical (non-ontological) domains (Bryant, 2008). Wilber (2012a) appears to interpret CR's association of ontology with the real, and its criticism of the epistemic fallacy, as identical with a particular metaphysical stance: the ontological privileging of non-conscious stuff and a violent (first-tier, materialist) fragmentation of being from knowing. I hope the discussion above clarifies that this is not the case, but there is still an important point to be made. Throughout the essay, Wilber (2012a) highlights IT's panpsychism or pan-interiorism as a distinguishing feature which sets it apart from CR's (supposed) split or siloed ontology, and which immunizes it from any criticisms related to the epistemic fallacy. Unfortunately (or fortunately, for the collaborative possibilities that still await IT and CR in the future), I believe Wilber is wrong on both counts. I will address the second point first, since it is most relevant to the discussion above. While CR's critique of the epistemic fallacy entails an implicit critique of certain metaphysical models (namely, empiricist and actualist ones), and while it is committed to realism, it does not require adherence to a specific ontological model, particularly not of the reductive materialist sort. This means, I will argue, that CR's advocacy for a stratified ontology is relevant even within a panpsychic context, as are its concerns about the epistemic fallacy. In two previous papers (Alderman, 2012; Alderman, in press), I suggested that IT can evade the full brunt of the critique of the epistemic fallacy only to the extent that it posits a Kosmos populated, not just by perspectives, but by real holons or sentient beings. I still believe this is the case, and I will argue for a version of this below. But this possibility hinges on how holons or sentient beings are presented and conceived; if they are conceptualized in a purely empiricist or actualist fashion, as Wilber (2012a) appears to do in his recent essay, Bhaskar's critique still applies. To facilitate this next step in our inquiry, I will again isolate a couple relevant quotes from the essay:

The first two quotes reveal the strong Whiteheadian influence on Wilber's ontology. I will return to this point in a moment. All three statements emphasize the idea that being is, to a large extent, dependent upon, and is essentially definable as presence to or for, consciousness, the third quote most strongly: different epistemologies call forth different ontologies, and different ontologies correlate with different epistemologies. It is not difficult to ascertain that epistemology is subtly privileged here: it is enactive or generative of ontology, whereas ontology is merely correlative with specific modes or forms of consciousness. This applies to Wilber's Whiteheadian account of sentient holons as well: their ontic reality is identified with their prehension by, i.e. their appearance to or for, other sentient beings (whether an external other or a future self). As should be clear, this is a variant on the empiricist and actualist ontologies that CR critiques. Ontology or being is defined purely positively here as appearance-for in present awareness; there is no allowance for withdrawal or ontic excess. A simple definition of the real in CR terms is as the irreducibility of a being to knowledge or experience of that being. As noted above, the real includes experience but is not reducible to it; objects or beings also include an intransitive dimension. Wilber (2012a) attempts to draw a correlation between his notion of subsistence and CR's intransitive level—pointing out that, while atoms (for example) can be said to ex-ist, or "stand out," only for beings at a given level of cognitive development, they nevertheless subsist prior to that. But as Wilber's subsequent remarks make clear (i.e., that the level of what subsists also depends on and changes with each level of consciousness), Wilber's concept of subsistence still trades on the (epistemologically fallacious) concept of being as appearance-for, here simply extended diachronically instead of synchronically. Hedlund (2015) observes, on similar grounds, that Wilber's postmetaphysical enactivism might be more aptly named (en)actualism. I appreciate this remark, and believe it names just the sort of issue I've been discussing above, but I would like to stress that this does not entail that an enactive model of cognition must necessarily be identified with metaphysical actualism. Varela's (1991) enactive model of cognition, like IT and CR (see below), attempts to steer a path between metaphysical realism and idealism, but it does not do so in a way that commits it to the Whiteheadian form of actualist correlationism that informs Wilber's particular interpretation of enaction. In making these remarks, I want to be clear that I do not think Wilber's (2003, 2006, 2012a) incorporation of Whitehead's work into his model is a mistake. I share Wilber's admiration for the depth and profundity of Whitehead's philosophy, and I am grateful that it is, in fact, currently flourishing in modern speculative realist and process-oriented, Polydox theological circles (e.g., Shaviro, 2009; Harman, 2011; Faber, 2011). However, regarding Whitehead's account of the co-creation of entities through prehensive unification, which Wilber (2003) follows and extends with his four-quadrant model, CR (and Levi Bryant's CR-informed Object Oriented Ontology; see below) would recommend a subtle modification of the account that would deliver it from the problem of actualism that CR has so carefully critiqued. In a blog entry on the affinities and differences between Whitehead's process ontology and OOO, Levi Bryant (2010) comments that he finds Whitehead's three-fold model of prehension—namely, that prehension involves a prehending subject, a prehended datum, and a subjective form of prehension (the way an actual entity prehends another entity)—closely consonant with an object-oriented understanding of "inter-object relations," including the related concepts of withdrawal and translation. Bryant (2010) interprets the third point, the subjective form of prehension, in terms of the second-order cybernetics of Bateson and Luhmann: information is always internal to autopoietic (or allopoietic) systems, intimately related to their distinctive structures, rather than a "message" that is transmitted, intact, between systems. But since information here is understood in terms of difference—a "difference that makes a difference," selecting unique system states within prehending entities—then the prehending entity cannot be identical with its prehensions; it must withdraw from or exceed its relations to other entities. This is where OOO differs with Whitehead's process ontology, Bryant argues, and why OOO would suggest, instead, a four-fold model of prehension (discussed below). Whitehead defines an actual entity as nothing other than the concrescence of its prehensions, in effect identifying the subject with its perceptions or experiences. But if an object is nothing other than its perceptions, then it is nothing in itself. It has nothing it can bring to its perceptions—no structure—and thus no "how" or subjective form of prehension. Bryant (2010) therefore argues that further differentiation is needed to make for a coherent model of inter-entity relations: "the subject/substance that does the prehending (the real object), the datum prehended (another real object), the subjective-form under which the datum is prehended (the organization or endo-structure of the real object), and the sensuous object (Harman) or system-state (me) produced in the prehending" (para. 8). When the prehending entity is defined as consisting only of its previous prehensions, Bryant maintains, this misses the withdrawn, mediating endo-structure of the entity (Bhaskar's generative mechanisms or intransitive level) which translates and gives subjective form to its emergent prehensions. In one section of his response to Critical Realism, Wilber (2012a) discusses at length the enactive trinity at the heart of Esbjörn-Hargens' (2010) Integral Pluralism: the Who, the How, and the What (or Epistemology x Methodology x Ontology). He accepts this formulation, but argues that Esbjörn-Hargens should be even more forceful in his claims about the roles that Epistemology and Methodology play in the actual co-creation of multiple objects. However, if Bryant's (2010) analysis above is correct, then Wilber's (1995, 2003) integral or tetra-enactive reframing of Whiteheadian prehension, while expanding it to better account for intersubjectivity, will nevertheless remain prone to conflating the Who and the What (or to subordinating the latter to the former) as long as it lacks adequate means of accounting for withdrawal. It will be insufficient, in itself, to address the issues of actualism or the epistemic fallacy discussed above. To put this another way (and to recapitulate the ground we have covered above): A Critical Realist definition of the "real," as the irreducibility of things to our knowledge of, or access to, them, does not require or presuppose a particular kind of metaphysics (whether materialist, participatory, or panpsychic); it simply suggests that whatever "is," exceeds or withdraws from, or cannot simply be reduced without remainder to, our knowledge of it. The reasoning behind such an argument has been spelled out above. Without acknowledgement of such an ontic excess, of withdrawal or absence, we can hardly make sense of our experimental, inquiry-centered, exploratory, and injunctive knowledge disciplines; or, as both Harman (2011) and Bhaskar (2002b) argue, we could not make sense of process or change. Thus, I am suggesting that the 'ontic' aspect of Morrison's 'ontic-epistemic' vertical (or Immanent/Transcendent) axis be read, at minimum, as an acknowledgement of this withdrawn depth, this 'excess' which escapes reduction to any present act of knowing. This kind of distinction can still be made within a nondual, pan-semiotic worldview (Bhaskar's metaReality is nondualist), so it is not an advocacy for the kind of 'fractured' or flatland metaphysics that Wilber (2012a, 2012b) is concerned about. And the epistemic domain, which lies along Morrison's (2007) Transitive axis, is the real domain of our modes of knowledge, both our models of "how we know" (epistemology) and our models of "what we know" or "what exists" (ontology). Here, epistemology and ontology are rightly seen as inseparable aspects of a whole; they co-arise, dance together, and mutually influence each other in semiotic and energetic interplay. Such a view is compatible with Varela's enactive orientation, which argues that "what ex-ists" for us (or any sentient being) as a real and causally effective domain of distinctions is inseparable from the (embodied) Who and How of knowing. But the epistemic/ontic distinction which transects and supports this (but which does not limit us to one kind of ontology) allows us also to avoid reducing or conflating "what (phenomenally) ex-ists" (or even subsists) with the full being of that with which we interact. About the latter, the most this model says is, "Do not reduce what beings are entirely to how they are known or enacted, whether synchronically (ex-istents) or diachronically (subsistents); there is a hidden ontic depth or excess which must be acknowledged as well." Regarding Wilber's (2012a) claim, mentioned above, that IT's panpsychism—its nondual integration of materialism and idealism—is what sets it apart from CR/mR and most other philosophies, this notion is fairly easily (and happily, for those of us interested in future collaboration) dispatched, at least in the case of mR, with a quote from Bhaskar's (2002a) The Philosophy of metaReality: Before I come on to dialectics of action, it is important to dwell a bit more on the question of embodiment, particularly in relation to the old dispute between 'materialism' and 'idealism'. Because everything is implicit in matter, enfolded in or diachronically emergent out of it, and because it can be transcendentally identified in consciousness, including higher (including supramental) levels of consciousness, matter must be regarded as a synchronic emergent power of consciousness as well as consciousness being regarded as a diachronically emergent power of matter and, at any one time, a synchronic emergent power of matter. Considering now matter as a synchronic emergent power of consciousness, this is to say that consciousness is implicit, enfolded, involved in it. Insofar as this enfolding happened, we would have to say it involved a process in time, or at least a diachronic process of creation, so we have also matter as a diachronically emergent power of consciousness, the product of a logically prior moment of involution, prior to its being enfolded, and far prior to its being unfolded in the natural process of evolution we are all familiar with... Can we therefore say that matter and consciousness are on a par? No. We have no grounds for supposing that all consciousness must presuppose matter, whereas we have grounds for supposing that all matter is implicitly or explicitly conscious. (p. 21) This passage is lengthy, but I have quoted it in full because it so neatly encapsulates mR's similar integration of idealist and materialist metaphysics, including an involutionary account of creation which appears quite similar to Wilber's (1995, 2006). The involutionary element may not be a welcome one with all Integralists—some of whom, like myself, would prefer to avoid positing an absolute beginning to the universe[5]—but it nevertheless indicates that there is greater common ground between these approaches than Wilber apparently suspects. There are several other important comments and criticisms of CR that Wilber offers in his essay that I have not yet addressed, but given their relevance to the integral and participatory models of interreligious relationship that we will be discussing, I will take them up in the next section—to which I now turn. Integral Religious PluralismWe have taken a long detour to get to this point, but I believe it was a necessary one. In "Kingdom Come," my initial recommendation for an Integral pluralist approach to religion was wedded quite closely to Wilber's postmetaphysical theory of enaction (and to Ferrer's participatory metaphysics). In order to avoid the well-known theological and ethical problems associated with religious exclusivism and inclusivism, and to avoid as well the subtler issues with identist pluralism outlined at the beginning of this paper, I proposed (initially without knowledge of Sean Esbjörn-Hargens' (2010) related work in the area of climate studies) an integral ontological pluralist model of spiritual realities to account for, and attempt to do justice to, the incredible diversity of the world's religious landscape and the plurality of often-incommensurate spiritual worldspaces and 'ultimates.' Following Wilber's (2003, 2006) postmetaphysical model of integral tetra-enaction—in which, famously, there is "no single dog," only plurality of dogs enacted by different sentient beings or even the same sentient being at different stages of development—as well as Ferrer's (2002, 2008) model of participatory enaction[6], I argued that spiritual realities should no longer be seen as eternally self-existing metaphysical dimensions of being, but rather as ontologically rich, co-created or -enacted phenomena. In "Opening Space for Translineage Practice," I was interested in further exploring the ontological implications of the integral postmetaphysical framework, using these insights to outline a non-reductive approach to trans-lineage spiritual practice capable of concurrently holding, and preserving, the concrete particularity and unique potential of the world's wisdom traditions. How does one simultaneously practice Buddhism and Christianity, for instance, in a way that is coherent and maximally inclusive, without violating the integrity or undermining the potential of either? The topics covered in the latter paper are too complex to review in the short space we have here, but one element of that exploration is particularly relevant to our present discussion. Without knowing Bhaskar's (2002b) term for it yet, I began to recognize the problem of ontological monovalence—of a purely positive, (en)actualist account of being—that was implicit in the current formulation of integral postmetaphysics. I saw that it was difficult to maintain the integrity of beings and objects without also including some category for the un-enacted, for ontic excess or withdrawal. To address this, I introduced Bhaskar's concept of the epistemic fallacy and an OOO-influenced framing of withdrawal (discussed above), as well as a modified version of Latour's principle of irreduction (which is the principle of the irreducible particularity of beings). Regarding the latter, Latour (1988) contends that 1) no object, actor, event, or actuality is ultimately reducible to any other; and concurrently, that 2) it is nevertheless always possible to perform, or enact, such reductive analyses, with the knowledge that such reductions come at a cost and will always, by definition, entail a loss in the form of distortion or oversimplification. In my reframing of his concept, I argued that the irreducibility of beings is found precisely in (and as) their potentially infinite reducibility (i.e., relationality). Holding these concepts together within the context of the integral postmetaphysical framework, I argued for seeing individuals and their temples, practice traditions, and institutions as (sacred) objects in the OOO sense: as generative (en)closures, each evolutionarily emergent; each irreducibly particular in its emergence, both entangled in relation and ontically withdrawn; and each capable of the generation or enactment of real, unique differences in the world. My recent engagement with CR and mR, however, has made me aware of opportunities for the deepening and refinement, as well as possible revision, of the model for interreligious relations that I have developed to date. As I believe the foregoing discussion of Wilber's (2012a) essay makes clear, CR presents IT with some immediate (but not indigestible) challenges. I had already begun attempting to address some of the issues CR identifies, primarily by drawing on OOO and Speculative Realist sources, but CR (or, really, mR) is closer to IT in animating spirit and integrative scope, so it may ultimately prove to be the better interlocutor. One immediately identifiable refinement to my suggestion that IT include a category for the withdrawn is to go ahead and adopt CR's full, three-tiered stratification of being, to include the actual as well as the empirical and the intransitive/withdrawn. With its panpsychic ontology, IT might insist that the level of the actual should never be regarded as wholly unobserved (by any sentient being whatsoever), since there will always be some implicit form of consciousness, element of prehension, or semiotic exchange involved in any material or energetic process. I do not think this poses any problem, since the actual (as a potentially unobserved event) can nevertheless always be thematized as a constitutive element of being independent of any particular perceptual experience or empirical observation[7]. Similarly, the concept of the irreducible particularity and uniqueness of holons or sentient beings—what Wilber (2006) calls Unique Self—finds a loose analogue in Bhaskar's notion of concrete singularity. Bhaskar (2002a) claims that all beings are concretely singular, with irreducibly unique ground-states. However, since ground-states are all connected at and with the nondual cosmic envelope, he frequently pairs this concept with the principle of dialectical universality, which is the notion that all beings are not only concretely singular, but also intimately enfolded within and co-present to one another. I will say more about this concept in a moment, when I am discussing Bhaskar's metaRealism in more detail, but first I will just register that Bhaskar's paired notions of concrete singularity and dialectical universality complement and potentially complete the account of "irreduction" or particularity that I mentioned above. The concept that the irreducibility of beings is related to their potentially infinite reducibility or relatability suggests the (logically necessary) pole of universality that Bhaskar highlights, but it had not been fully unpacked or thematized in my own writings. In much of my discussion throughout this chapter, I have focused on Critical Realism, which is a philosophy of non-identity or duality, rather than on the newer approach of metaReality, which is a philosophy of identity or nonduality.[8] This is in part because Wilber's (2012a) essay was primarily directed at CR; and, in part, because elements of the integral postmetaphysical model involve certain theoretical gaps or conflations which I believe are best addressed by concepts unique to CR (which mR also includes). With the flowering of the spiritual turn marked by the development of metaReality, Bhaskar (2002a, 2002b) thinks being (or, more formally, the interplay of ontology and axiology) in seven dimensions or stadia: Being per se; as process or becoming (including negativity and determinative absence); as a totality or whole; as incorporating transformative praxis and reflexivity; as spiritual; as (re)enchanted; and as nondual. In light of the latter, most fundamental dimension, nonduality, Bhaskar (2002a) (re)conceives of the philosophical and spiritual themes of unity and identity as involving, and as fully consistent with, an understanding of reality as ontologically differentiated, complexly layered or stratified, and dynamically developing or processual—rejecting, for instance, the concept of spiritual identity as a vast, non-differentiated, all-encompassing whole (p. 29). Further, Bhaskar (2002a) posits three modalities and three mechanisms of nonduality. The three modes through which nonduality functions are 1) as the ground-state of all other states of being and forms of consciousness, linking all inseparably together through the cosmic envelope; 2) as the 'ordinary moment of transcendence' which makes all perception, communication, and action possible (e.g., the non-conceptual identification of perceiver and perceived in the act of watching a ball game, or communicating to a loved one, etc.); and 3) as the fine structure or 'deep interior' of any moment of consciousness or state of being (involving qualities such as bliss, emptiness, suchness, love, identity, and so on). The three mechanisms of nonduality consist of transcendental identification (again, which is ingredient in any moment of perception or activity); reciprocity (which is the mutual or sympathetic resonance of beings in their ground states, or the commonality which allows beings to connect and relate); and co-presence (which is the enfolding or implicit participation of all beings in one another, without negating the particularity or uniqueness of each being). In terms of both spiritual and social emancipation or flourishing, Bhaskar (2002a) believes that the ultimate good for a sentient being is to live consistently or in harmony with its ground state. But because all beings are related, explicitly in society and implicitly at the level of the cosmic envelope, the freedom and flourishing of each being is necessarily both the condition for, and the consequence of, the freedom and flourishing of all (p. 10). Further, in light of the notion of co-presence—according to which all beings are implicit in each being—self-development or self-realization is necessarily open-ended, since co-presence opens up a wealth of evolutionary potentials or pathways. "In any event," Bhaskar (2002a) writes, echoing Wilber's (2006) own distinctions between vertical and horizontal enlightenment, "we have the conclusion that since evolution is an open-ended process, awakening, realization, or enlightenment need to be relativized and conceived as in principle subject to evolution, so that they cannot be identified for any one being or species in an absolute manner" (p. 80). The collapse or over-coming of subject-object duality—not only in peak spiritual experience, but philosophically as well—is related to the sixth stadium of being, (re-)enchantment. Here, as the semiotic distance maintained by the detached, separate observing ego is overcome, being is experienced as immediately and intrinsically valuable, meaningful, creative, communicative, and spiritual (Bhaskar, 2002a, p. 46). The (re-)enchanted world is participatory in at least two powerful senses: 1) the ordinary objects of the world are experienced as semiotically charged, open to and bearing a multiplicity of meanings (the referents become signifiers); and 2) when the self is no longer detotalized (detached and held aloof from the complex totality of a situation), perception and communication become real, causally effective events in the world. This is similar to a point that Jorge Ferrer (2008) also makes: if semiosis goes all the way down, as Peirce (1991) maintains, as a feature of reality at all levels, then language becomes not simply a representational mapping of the real world without any ontological depth of its own, but a living performance of, and thus also a means of transformative, participatory engagement with, that world in its ontic fullness. In Bhaskar's (2002a) terms, (re-)enchantment entails a trialectic of being, agency, and perception, where a change in any one—and (re-)enchantment involves changes in all three—effects a reciprocal change in the others[9]. Although there is a great deal more to the philosophy of metaReality than I have identified above, these points will be sufficient to contextualize Bhaskar's (2002a) proposal for a metaRealist theory of comparative religion, which is immediately relevant to our project here. Bhaskar (2002a; Bhaskar & Hartwig, 2012a) maintains simultaneously that the world's religions all entail a single path with a single general end, and many paths with many unique ends. Regarding the former, Bhaskar (2002a) writes, Every religion entails a single path, involving a commitment to individual and universal self-realization, and involving the equivalence of the principles of the primacy of self-referentiality (whether this be given in a Vedic, Egyptian, or Platonic declension) and commitment to a eudaimonistic society more generally, to universal self-realization or the project of theosis. The importance of the principle of self-referentiality is that I can only ever act myself, that is all my action is action on or by myself. But the effects of my action are in principle infinite and I always act so as to maximize the self-realization of all beings everywhere. Thus we find within Mahayana Buddhism the ideal of the Bodhisattva, a beautiful rendition of the equivalence of these principles. (p. 327) Additionally, religion in this very general sense is participant in an even more general "path" which Bhaskar (2002a) believes obtains across multiple (political, religious, cultural, personal) contexts: the path of self-clearing (through shedding elements of heteronomy within the psyche, diminishing egocentricity, clearing the mind and heart, and refining the physical/energetic body), thereby allowing individuals to better align with their ground states in the accomplishment of personal and social goals, and in the service of individual and collective flourishing (p. 332). Regarding Bhaskar's (2002a; Bhaskar & Hartwig, 2012a) concurrent claim that there are also many paths and ends, we touched on an aspect of his reasoning for this above: In a nondual, open, evolutionary context, there are many possible forms of realization, and realization or enlightenment itself is evolving. But he approaches this otherwise as well. Applying the "holy trinity" of critical realism—ontological realism, epistemological relativism, and judgmental rationality—to the religious context, Bhaskar argues that, while ontological realism about God or the divine (whether considered as the totality of ground-states, which is Bhaskar's formulation, or otherwise) can be consistently maintained, epistemological relativism entails there will inevitably be multiple means of approaching, accessing, interpreting, and experiencing this reality; and judgmental rationalism ensures that interpretations and practices relative to the divine or a tradition's ideals are always open to rational inquiry and evaluation (for theory-practice inconsistencies, etc) (Bhaskar & Hartwig, 2012a). While Bhaskar's model would appear to endorse a single ontological ultimate which is the same across all traditions, he allows for it to be richly differentiated (say, when conceived as the totality of ground-states) and also open or non-determined and creatively responsive or generative (meaning, following Shankara, that the divine actively manifests itself differently in different contexts or times[10]). This distinguishes Bhaskar's model from Hick's neo-Kantian formulation—in which the divine or Real-an-sich is ultimately unknowable and inaccessible—, and places it in the neighborhood of Griffin's (2005) or Heim's (2001) differential pluralism, or possibly even Ferrer's (2008) participatory model. Regarding the latter, there are several commonalities and differences to be noted. Like Hick, Ferrer (2008) defines his unifying spiritual power as unknowable or a Mystery, but he does so for a different reason: it isn't inaccessible, it is open and undetermined (p. 150). In the participatory account, this divine Mystery or spiritual power is also co-creative and responsive, playing an active part in the participatory enaction of spiritual realities. Bhaskar's description of the differential manifestation of the divine isn't as dynamic or co-creatively interactive as Ferrer's (Bhaskar & Hartwig, 2012a), but there may be common ground here for meeting nevertheless. Ferrer, I expect, would be uncomfortable with Bhaskar's more positive depiction of the divine or ultimate reality, but Ferrer (2008) himself may have a clearer picture of it than he acknowledges. For instance, combing Ferrer's (2009) essay, "The Plurality of Religions and the Spirit of Pluralism," for the descriptors he employs to refer to the metaphysical ultimate necessary to his participatory account (which may be understood as the metaphysical principles necessary for a participatory conception of reality itself), I was able to isolate the following thick description: A power, force, mystery, or reality, considerable alternately as life, spirit, or cosmos, which is undetermined, dynamic, generative, creatively unfolding, ultimately unified, ontologically rich, radically open, interrelated, and responsive to participatory engagement. This is not very distant from Bhaskar's own descriptions. Bhaskar's (2002a) articulation of both the singularity and multiplicity of religious paths is also reminiscent of Ferrer's (2008) "ocean with many shores." In this understanding, the ocean that all or most religious traditions share is the ocean of emancipation—the shared value, process, and outcome of overcoming egocentricity in and for the fulfillment of self and other—whereas the different shores are the different, ontologically real spiritual worlds, beings, and phenomena unique to each tradition (here, understood as co-creatively enacted, not pre-existing and "discovered"). Both accounts locate the greatest commonality among traditions, and possibly the greatest potential for mutual accord, in the pragmatic sphere, while acknowledging and allowing for a diversity of theological or metaphysical interpretations or enactments. In general form, this strategy is akin to Hick's approach as well: he argues that spiritual traditions, while often quite divergent in their metaphysical worldviews and practices, nevertheless typically involve and encourage movement away from self-centeredness towards greater Reality-centeredness. Bhaskar's approach appears to fall somewhere between Hick's and Ferrer's models, in this regard. Like Hick, he locates many of the metaphysical differences among traditions to the empirical or transitive domain, and accepts also the notion that the general trajectory of spiritual growth is from self-centeredness to reality-centeredness (understood here as harmony with the individual's unique ground-state), while rejecting Hick's neo-Kantian conception of the divine as an utterly inaccessible noumenon. Like Ferrer, he accepts that many diverse spiritual phenomena are real (rather than merely cultural conventions), and that the divine is responsive (in that it may manifest differently in different contexts), but he holds that an ontologically coherent account of spiritual reality must also posit an intransitive dimension in relation to the plurality of phenomenal manifestations. This puts Bhaskar's model in some tension with both Ferrer's (2002, 2008) and Wilber's (2006, 2012a) "many worlds" approach. As discussed previously, locating "reality" in the empirical alone, without acknowledging an intransitive domain, courts incoherence. Ontological pluralists who aim to avoid positing a single phenomenal world common to all beings nevertheless often end up presupposing certain common intransitive metaphysical factors which make such worlds possible. Arguably, we find this in the necessary qualities Ferrer (2008) assigns to the Mystery or creative spiritual power that unifies his account[11]. Similarly, Wilber's (2006, 2012a) postmetaphysical, "many worlds" narrative includes an implicit master ontology, which we might summarize as follows: The Kosmos consists of sentient beings which enact unique worlds (including each other) through their (real) stage-, structure-, and state-dependent perspective-taking, and this entails that reality is therefore fundamentally panpsychic or pan-interiorist: we must regard consciousness and being/matter as equally real and inseparable at all levels of existence and stages of development. Wilber asserts that there are multiple ontologies, each unique to the types (and levels) of sentient beings that enact them, but in order to tell this story of ontological pluralism, he must also commit minimally to the above universally applicable metaphysical principles. There may be many cosmoi, but in this telling, they are participant in one Kosmos: a Kosmos composed of co-creative, tetra-enactive holons or sentient beings. Wilber (2012b) remarks in his follow-up response to CR that, while he does not wish to ground his model in ontology in the fragmented way he (incorrectly) supposes CR does, the AQAL map is nevertheless "drenched" in ontology. But to the extent that Wilber attempts to limit "ontology" to the phenomenal realm of the enacted, thus denying an intransitive domain, his system will self-contradict and flounder in incoherence. For instance, Wilber argues for the equal, if concurrent or inseparable, reality of epistemology and ontology for all beings at all levels—all the way up, all the way down. But this requires that this distinction be taken as real, not merely empirical. For, as Bhaskar (2012a) points out, it is only when the distinction between epistemology and ontology "is regarded as real, and so as falling within ontology, [that it can] be sustained. (If it falls at the same time within epistemology, then we are back to the epistemic fallacy)" (p. 40). The issue between IT and CR, then, is not so much that IT lacks grounding in ontology, but whether its ontology is an adequate or coherent one. I believe CR offers IT a powerful explanatory critique, which reveals certain gaps or points of incoherence in its account. In my view, most of the distinctive elements of both integral postmetaphysical and participatory approaches (such as their mutual assertions about the real, rich plurality of worldspaces available through enaction, so important to the pluralist models of spirituality reviewed here) can be retained, and even reinforced, if they adopt something akin to CR's stratified realist ontology, which distinguishes between empirical/phenomenal and intransitive domains[12]. Co-Presence and the Circumincession of Religious TraditionsIn his initial reflections on interreligious relationship and dialogue, particularly in From East to West, Bhaskar (2000) explored the possibility of a synthesis of Eastern and Western forms of spirituality. But with the transition to the metaRealist phase of his philosophy, he has abandoned this approach and instead considers religions alongside each other and in light of each other, each as a unique whole, without needing to force reconciliation. I am speculating a bit when I venture this, but I believe this change in orientation might be traceable, in part, to his adoption of the (non-dualist) view of co-presence. The principle of co-presence is akin to a generalized form of the Catholic Trinitarian doctrine of circumincession, which is the doctrine of the reciprocal indwelling within one another of each of the Three Persons of the Godhead. But in Bhaskar's (2012a) formulation, circumincession or co-presence is not a truth pertaining only to God; it is a truth about all things, that all things indwell each thing. On this view, each religious practitioner, and each tradition, can be seen to enfold the totality, or the potential for the realization of any aspect of the totality. There is thus no need for an external synthesis, since each has implicit within it the potential available to all beings in the Kosmos. Does such a view vitiate interreligious relationships? Does it undermine the need for dialogue across traditions—rendering each tradition a self-sufficient whole, with no need to interact with or learn from others? The possibility for such an interpretation is present, of course; but in my opinion, the principle of co-presence or universal circumincession has great potential to effect the opposite result: that is, to enrich and reinforce the entire field interreligious (and even intercultural and interspecies) relationship. For, while each being or form is indwelt by the totality of all forms, and therefore has the potential to realize some aspect of each, in reality we only ever actualize a limited amount of that potential—developing richly along certain evolutionary pathways, perhaps, while leaving many others relatively unrealized. In interfacing closely with other traditions, we are afforded the opportunity to learn something about our own implicit capacities and potential forms being, which we may then unfold in our own unique ways. Interreligiously, such a model might inspire modes of encounter similar to Deleuze's becoming-animal: Not a process of imitation, not a conscious choice to adopt a costume or to mimic another being's ways, but the invitation to draw close to the other until, imperceptibly, in that zone of maximal proximity and indeterminacy, becoming eventuates. We awaken what is always already, but in so doing, it becomes what it never was. To my knowledge, co-presence has not been applied by Bhaskar to the field of interreligious relations in precisely the way I am suggesting here. But of the many gifts to be discovered in the philosophy of metaReality, I find this one to be especially rich in its implications for this field. As a term denoting the radical relationality, interpenetration, and/or mutual indwelling of beings in the cosmos, generalized co-presence finds analogues in the holographic principle of Edgar Morin's Complex Thought, in Ken Wilber's nondual inflection of holarchy, as well as in multiple religious archetypes of divine inter-independence (such as Indra's Net in Hinduism and Buddhism, in addition to the Trinitarian circumincession or perichoresis discussed above). This suggests that it will be especially valuable as a metatheoretic lynchpin, facilitating collaborative work among several prominent metatheories and religious systems. But it also has the potential to deliver, in a rather elegant way, many of the metatheoretic fruits that the Integral and participatory approaches seek: a non-reductionist, ontologically realist model of spirituality which allows for the acknowledgement of both the implicit unity of traditions, and of their richly differentiated modes of being, forms of realization, and evolving visionary worldspaces and horizons[13]. Throughout this chapter, I have focused primarily on the contributions CR and mR can make to Integral and related approaches—from its critique of the epistemic fallacy; to its stratified ontology; its "holy trinity" of ontological realism, epistemological relativism, and judgmental rationalism; its three modes and mechanisms of nonduality; its concepts of concrete singularity and dialectical universality; and in this last section, the interreligious and metatheoretic potential of its model of co-presence. If the arguments I have made here are sound, a Critical or metaRealist inflection of Integral Theory will enable IT to better deliver on its aim to provide a philosophically robust, meta-theoretical framework for religious or spiritual realities, and to legitimize religious contemplative traditions, postmetaphysically conceived, as viable and vital emancipatory vehicles for our time. It goes without saying, I believe, that both the integral and participatory models, in particular, have much to offer CR/mR in return—especially in the areas of mystical phenomenology and religious studies. Both possess sophisticated mystical and religious cartographies which can contribute to, and considerably expand, metaReality's soteriology and its theory of religion. For instance, in A Sociable God, Wilber (1983) offers five definitions of spirituality and at least nine different definitions of religion, the adoption of which could add considerable nuance to Bhaskar's rather monolithic treatment of these terms. Similarly, Integral Theory's insights into psychological and spiritual development, and the related concept of the pre-trans fallacy, may help to flesh out mR's more general and abstract account of religious development, and perhaps also provide a corrective to its latent Romanticism (where spiritual realization is conceived primarily as the removal of heteronomous obstructions to our original completeness and perfection). As of yet, neither Integral Theory nor Critical Realism has made significant academic in-roads into the field of religious studies. Both have been used recently to inform various experimental Christian and other religious theologies[14]—and this, in itself, is notable and worthy of critical examination by religious studies scholars—but neither has made substantial theoretical impact on the discipline itself. This can perhaps shift if IT and CR/mR scholars make more of an attempt to engage and dialogue with current thinking in the field. Such engagement might entail critical reflection on and response to current post-colonial, feminist, and neo-pragmatic developments in (and criticisms of) religious studies, as well as constructive dialogue with prominent thinkers and movements who share some affinity with IT, mR, and participatory studies in working towards a post-secular re-legitimization of religion and spiritual phenomena beyond dominant postmodern or "exclusive humanist" (Taylor, 2007) interpretations[15]. Given their broadly meta-theoretic and trans-disciplinary scope, neither IT nor mR need restrict its contributions to contemporary religious thought to work within the academic field of religious studies itself; rather, I believe they will operate most constructively at the interfaces of theology and religious studies, as at other related boundaries as well: intra-religious, interreligious, and extra-religious (i.e., between religion and science, or religion and secular-atheist culture). For instance, in Integral Consciousness, Steve McIntosh (2007) argues that the ideal role for IT in contemporary culture is not as a new religious system in itself, but as a philosophical intermediary between religion, science, and other important cultural domains. Similarly, in Critical Realism and Spirituality, Roy Bhaskar suggests that in a religious context CR/mR might best serve as philosophical underlaborer or "handmaiden to a range of theologies" (Bhaskar and Hartwig, 2012b)—its stratified ontology providing potential (post)metaphysical resources for multiple religious systems, and its holy trinity (of ontological realism, epistemological relativism, and judgmental rationality) both allowing for a robust soteriological pluralism, and providing practical grounds for intra-, inter-, and extra-religious dialogue. If future collaboration between IT and CR/mR is to be possible despite their philosophical differences—and my hope is that this chapter shows a way forward in this regard—I would like to see further work done in the following areas: