|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel.

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD

Fall of the Damned, 1470 (Oil on Canvas), by Dirk Bouts

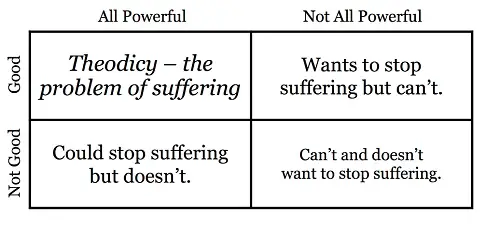

Why Do We Suffer?Theodicy and Integral AQALJoseph DillardWhy is there pain, suffering, and misery in the world? Mike McElroy has written a very thoughtful and wide-ranging exploration on the meaning of suffering from historical, religious, existential, and integral perspectives. His essay is called “Theodicy - A Missing Piece,” and is posted at IntegralWorld.Net. This essay represents an integration of his broad-based insights with my own interest in clarifying the role of morality in the context of an integral world view. What is theodicy?The problem of the existence of suffering largely arises out of man's search for meaning, since so much suffering is experienced as meaningless. What is it about humans that needs suffering to have meaning and purpose? Theodicy is essentially a religious concern, because religions involve deities, and some conception of the divine, the idea of God, divinity, or spirit stipulates something or someone who is responsible for goodness and for protecting us. When there is evil instead of good, suffering instead of happiness, and when we are left vulnerable and abused, what does that say about the idea of God? Here are the classical options:

Following Epictetus, Hume's famously asked, Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Why indeed? Hume, who was an atheist, was pointing out that the issue of theodicy strikes at the very heart of religion, if not spirituality. What does it say about humanity and human existence if suffering has neither meaning or purpose? It is a closely related issue, the nature of the moral, rather than the ontological implications of suffering inherent in the notion of deity, that challenges the transpersonal, the home ground of the spiritual. Theodicies start with an all-powerful (omnipotent) definition of spirit and then proceed to render it less than all-powerful. These are justified by Augustinianism and process theodicies following Whitehead, as not interfering with man's free will, or by Irenaeusism, so as to provide self-discovery of broader meaning and purpose. One of the fascinating things about the Augustinian variety of theodicy is that it justifies punishment as necessary to teach humans not to be evil and to learn to be moral. Therefore, an advantage of the question of suffering for society is that it can be used to legitimize punishment by the representatives of God. At its extreme it leads to extraordinarily bizarre and cruel justifications: “As God's servant, I am torturing you to death to teach you how not to be evil and how to be moral.” If this seems far fetched, read Christian rationalizations for the Spanish Inquisition. McElroy believes that ultimately it can be argued that all theodicies are a type of Irenaean theodicy. “Even the Augustinian theodicy is a form of soul-making in that we define ourselves in relation to how we choose to freely respond to either be for or against God's wishes and either grow as an individually responsible (and responsive) being in that regard or fail to grow individually thusly. Another classical Christian answer to theodicy is that offered by the early Church father, Irenaeus, echoing the Indian avidya-prajna formula. Evil exists to learn and grow. We need suffering in order to become better people, and in time we will reflect on our pain and realize it had a purpose in our lives. This “solution” is also representative of the impressive human capacity to rationalize. We don't need God or spirit to figure out how to learn from our mistakes or ignorance. In fact, the insertion of divinity into the equation only muddies the clarity and shifts focus from the task at hand: to learn from our errors. There is good reason why theodicy is widely considered among theologians to be the most difficult issue for religion to address. It is quite embarrassing, if not laughable, to see the pretzel logic, worthy of world-class contortionists, that these dedicated believers tie themselves up in as they attempt to square this circle. While the anthropomorphisms of Western monisms turn theodicy into Theo-idiocy, those approaches that embrace a formless, transpersonal, Universal consciousness or universal dharma, run into the same problems. One of the cruelest answers to the question of theodicy comes from both Hinduism and Buddhism: If you are suffering, it's your karma. You created it and deserve it. In fact, you need to suffer, because it is only through experiencing that suffering that you will learn how to meet it with humble acceptance and thereby be born into a future life of less suffering. This is the patently unfair “logic” that has supported both the Indian caste system and the general order of both Indian society and the economy of Buddhist monasteries for over two thousand years, and the inability to continue to deny and accept the discriminatory nature of this answer to the question of theodicy is what led to the abolition of the caste system in India in 1949. Among world religions, Buddhism does by far the best job of answering the question of the existence of suffering and evil. It does so by eliminating a divine power responsible for suffering as well as a real self that can and does suffer. If there is no cause, because there is no God, and there is no real effect, since there is no real self to suffer, then PRESTO! Problem solved! The suffering you experience is a delusion caused by your identification with a false identity. As we shall see, Wilber's integral echoes this “answer.” In practice, Buddhists hold to various conceptions of deity, of self, and do indeed experience suffering. However, all one needs to do is overcome one's ignorance of these truths in order to eliminate suffering, and we can do that by taking up the Eightfold Noble Path. For most people, this is a big “ask,” that the reason we experience suffering is 1) because of what we did in a past life, and 2) because we are ignorant. Also in practice, Buddhism teaches tools to support meeting the reality of suffering with equanimity, which is an approach it holds in common with Western stoics like Marcus Aurelius, and an approach I support. The Cosmological contribution to the question of meaningThe approach I will take here is fundamentally phenomenological, meaning it attempts to table as many of our assumptions as possible about the meaning of suffering and the nature of evil in the world and, in the tradition of Aristotle and Descartes, begin from the grounding of our perceptual experience. The result is a largely naturalistic approach, not a religious or even spiritual one, although the sacred dimension embraces all three - nature, religion, and spirituality. We start with nature because we can build on those “facts” “given” by our senses, but with the advantage that we have greatly extended senses today, which give us much improved “facts” upon which to build. Labeling suffering as evil, as in calling theodicy “the problem of evil,” is one of those assumptions to be tabled, because it immediately imposes upon and projects onto nature a state of relative morality or immorality. Mike McElroy: For example, the theologian John Hick, in Evil and the God of Love differentiates “natural evil,” and provides earthquakes, hurricanes, disease, and death as examples. He differentiates this from “moral evil,” as if the appellation “evil” was not itself a moral reference, and includes the evil actions people commit. A third type of evil is “metaphysical evil - evils that occur due to limitations on the part of God or the universe or logic in regards to what is possible and what is not, for example, (allegedly) not even an all-powerful God or Spirit can make the past not to have been. In this framing evil becomes not only an issue of morality, as in good and bad, due, at least in part, to supernatural forces, God, whether we want to define Him/Her/It as transcendent, immanent, both, or neither, but the cause of suffering. We now have created a dualism of good and evil in addition to the issue of suffering, where neither necessarily exist outside of the doctrine of theodicy. For example, non-human life suffers, but it does not contemplate the nature of suffering, which only adds another dimension of suffering to physical pain. Nor does nature turn suffering into a moral issue. Why not? Let us back off and look at the roots of existence and see what light they might be able to throw on this issue. We know the universe is almost completely dark matter and dark energy, with matter making up only a very small percentage of what exists. Dark matter is a form of matter thought to account for approximately 85% of the matter in the universe and about a quarter of its total mass-energy density, which contains 5% ordinary matter and energy, 27% dark matter and 68% of a form of energy known as dark energy. Dark energy plus dark matter constitute 95% of total mass-energy content. Of that small percentage of the universe that is “ordinary” matter, a much, much smaller percentage is what we call “life.” This means that almost all of reality, much more than 95%, is entropic, following the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics: winding down and moving toward a state of absolute equilibrium. The reaction of some idealists to the reality of the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics implies a deep rooted fear that the evidence points to a meaningless universe: Biologically, life is not maintenance or restoration of equilibrium but is essentially maintenance of disequilibria, as the doctrine of the organism as open system reveals. Reaching equilibrium means death and consequent decay. Psychologically, behaviour not only tends to release tensions but also builds up tensions; if this stops, the patient is a decaying mental corpse in the same way a living organism becomes a body in decay when tensions and forces keeping it from equilibrium have stopped.[1] This idea has been fought by many people, because they hear it as a statement of the ultimate, absolute, final meaninglessness of existence: Many recent creationists believe that the second law of thermodynamics came into being as a result of the Fall or the curse. I argue that this is not supported by Scripture, nor is it a defensible position from a scientific viewpoint. Instituting the second law of thermodynamics at the Fall needlessly causes problems for theology and science. Rather, I propose that the second law of thermodynamics came into the picture during the Creation Week as part of the created order (Nehemiah 9:6; Colossians 1:16).[2] That explanation makes it all better, doesn't it? We can be rather certain that life itself, which is such a small percentage of reality, doesn't care about the issue of suffering and evil at all. Yes, life does experience loss, death, and in its higher forms, pain. Life wants to live, to expand, or, to put it in exterior individual evolutionary and exterior collective system terminology, it wants to self-organize. In the exterior individual evolutionary sense, Varela and Maturana have called it “autopoiesis,” after the Greek “auto,” self, and poiesis,” or creation, production. Consider the sun. Does it care if Earth lives or dies? Such a belief would mean that the sun is not impartial, meaning consistent within itself, and instead it is affected by and dependent upon the welfare of that outside itself. One new age example of this I have run across is the belief that human activities, such as wars, cause sun spots. The logical conclusion is that, if this were true, the sun would be much less stable and dependable, because it is influenced by behaviors and “energies” beyond the laws of celestial mechanics. This turns the sun into something of a whimsical demigod, like something out of Urantia, rather than the largely unvarying source of energy that propels and sustains life. The implication is that the sun has to lack compassion, caring, and meaning in order to do what it does. Similarly, and by analogy, the vast majority of the universe has to lack not only these things but must remain formless in order to serve as a plenum of creativity, a womb out of which all these things can arise. Therefore, the universe has to be amoral, impartial, and oblivious to both suffering and evil in order to evolve to a place it can support the human biosphere. The highly influential systems theorist Ludwig von Bertalanffy brilliantly noted that evolution creates an increasing number of ways to experience life and therefore stress and suffering. The evolution of speech, thought, and the biosphere are examples, in that they are necessary prerequisites for the formation of the concept of theodicy and the subsequent paradoxes it generates. Without higher order evolution these dilemmas of good and evil, meaning, and the purpose of suffering, would not and could not exist. This introduces a profound element of realism into the narrative of idealist ascenders who believe that if we just get to “second tier” or experience this or that commodification of enlightenment, that we will enter the Age of Asparagus, or something warm and fuzzy. The reality is that the quest for enlightenment and ascent into the transpersonal levels inevitably brings with it greater sensory acuity and therefore more sensitivity to pain, for a greater spectrum of emotional awarenesses and responses, and therefore more forms of affective suffering, greater complexity of thought, a greater variety of skills, dispositions, and perspectives to balance, and therefore a greater risk of imbalance and failure, more essential elements to overlook, and the evolution of individual lines above and beyond our general competency to handle the challenges that are intrinsically associated with advancement. It is a lot like the sexual and emotional sizzle of romantic attraction; in our rush to make our dreams come true we blind ourselves to the downside risks. Bertalanffy makes this same point regarding stress, as a form of suffering necessary for evolution: Also the principle of stress, so often invoked in psychology, psychiatry, and psychosomatics, needs some reevaluation. As everything in the world, stress too is an ambivalent thing. Stress is not only a danger to life to be controlled and neutralized by adaptive mechanisms; it also creates higher life.[3] Suffering, in the form of stress, is necessary for the evolution of life and the development of humans. While psychology as well as physiology differentiate between distress, or catabolic processes, and distress, or anabolic ones, like exercise, both forms of “suffering” are pre-requisites for life and growth. One is not evil and the other good. Together, they generate a developmental dialectic. The implication is that suffering is not inherently bad, much less evil, and that this perception is largely a human projection based on our emotional preferences and our noospheric expectations. Therefore, what we might conclude is that suffering is not the problem but rather our preferences and expectations. Focus on suffering generates theoditic paradoxes while attending to our preferences and expectations generates clarity and objectivity. Meaning as a human valueMeaning is something that humans impose on nature from the interior collective quadrant of value, culture and hermeneutics. Meaning is not a value or quality that exists apart from human psychology. This statement sounds radical because it goes against our sense of value itself; we want our lives to have value and we want life to have value. I do not disagree; we can and should have both. However, we need to look for the source of meaning as our own value system and therefore as something within our own control. Externalizing the causes of suffering not only leads to insolvable conundrums but takes our power away as well. If the causes of suffering are external to us, so are the solutions. Therefore we have to change life, God, or others in order to reduce suffering. If we cannot, the implication is, that like Sisyphus, we are destined to suffer. If we don't think life is meaningful enough, we can change that; we are not compelled one way or another on that issue by life itself. And yet there is something fundamental about human psychology that wants or even needs an exterior source of meaning, in a theme echoed by figures as diverse as Freud and his parentally-derived superego, on the one hand, and Lakoff's view of conservative and liberal political persuasions as derived from authoritarian and nurturing styles of parenting, on the other. Meaning and theodicy are examples of issues created by our culture. We think we are thinking our own thoughts when we are merely echoing the thoughts of our scripting. The purpose of suffering is generated by our perception of it, by our world view, our history, our culture, and our sense of self. It is not generated by life, spirit, God, nature, or “reality.” We know this because of the variety of responses to suffering that are possible and what extremely different consequences they produce. For instance, if someone kicks us we can cry, get angry, attack, withdraw, be puzzled, ask questions, or laugh. Which of these we choose creates a completely different degree and experience of experience, that may or may not include suffering. Meaning is a personal choice and misery is optional, even if pain and injustice are relatively less so. That, of course, does not keep life from being sacred, a source of awe, majesty, ennoblement, and inspiration to be a better person in every way. The purpose, telos, or teleology of suffering is up to us. It is not written in the stars, to be found in scripture, or in the words of wise men and women. Consequently, suffering can indeed be dysteleological, meaning that it serves no purpose whatsoever. Confucianism and theodicyWhile all religions offer a theodicy, and the Western ones tend to frame it as “the problem of evil,” it is curious that Chinese traditions, and in particular, Confucianism, which is often considered a form of humanism rather than religion, does not. If one does not support the three basic propositions of the nature of spirit, as omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenificent, then there is no contradictory evil. This partially explains the success of Chinese Confucianism - it successfully avoids this trap. Suffering is diagnosed by both Taoism and Confucianism as disharmony or chaos, not due to evil, ignorance, immorality, or sin. The solution to disharmony for the Chinese is the establishment of order. When one lives in alignment with the Tao there is harmony and no chaos. The experience of suffering is met with the question, “What do I need to do to get my life back in balance?” In Chinese folk traditions, which are a mixture of shamanism and Buddhism, the answer is to placate the spirits of ancestors. In Confucianism, it is the re-establishing of harmonious social relationships. There is no idea that Heaven creates suffering, but rather that chaos is built into nature, as is order. Chaos is simply a sign that things are out of balance. Notice that this formulation is not one of blame or guilt; instead it is entirely pragmatic. It asks, “What do I need to do to restore balance?” One could argue that Chinese humanism is a monistic response to the problem of human suffering by viewing chaos as the yang balancing the yin of harmony, and that when these are combined one arrives at a monistic answer to the problem of suffering. I suppose this could apply as long as this solution were viewed as a sacred and naturalistic monism instead of a metaphysical, spiritual, or religious one, without implications of deity, morality, or evil. Like Chinese Tao, cosmology reveals a universe that is both monistic and profoundly dualistic, depending on how you want to look at it. We can view entropy and negentropy as two polarities of one overarching whole. However, this would seem to be something of a long stretch, as negentropy in the cosmos makes up only a very tiny fraction of any proposed monistic whole. At the other extreme, we can view entropy and negentropy in eternal opposition and generate some sort of cosmic metaphysical dualism worthy of Zoroaster, Mithra, or the Manichaeists. The theologian John Hick notes that Dualism as a theodicy, on the other hand, rejects this final harmony, insisting that good and evil are utterly and irreconcilably opposed to one another and that their duality can be overcome only by one destroying the other. But there exists no necessity to generate a polarity between theodicy and nihilism. To not ask, “Why is there suffering?” Does not imply the giving up on meaning or on life. Humanism, whether of a Chinese, Western, or amalgamation of the two, does not have to be thought of as a late personal outgrowth of rationalism. Indeed, in China human was a manifestation of an early personal level of societal development. Therefore, it makes more sense to look at the values of humanism as intrinsically moral ones that apply equally to all levels of development rather than identified with one or another. Theodicy and the Drama TriangleMcElroy thinks that no one says what the meaning of suffering is. It seems to me that the opposite is true, that everyone has their own answer. The most common answers, psychologically speaking, are the three positions within the Drama Triangle. Individuals and entire ethnic groups and nations, like Jews and Israel, create an identity around the safest, most stable and secure of the three positions, the role of Victim. “Victim” is capitalized to differentiate it from victimization, which is what happens when we are rear-ended or get coronavirus. But even in such cases, legal systems mete out proportionate accountability. Victims, as differentiated from “victims,” define themselves as persecuted, abused, helpless, and powerless, and manage to maintain this delusion even when they have more than two hundred nuclear warheads and largely control both Houses of Congress and the Presidency of the most powerful country on Earth regarding issues that are material to it. The reason the position of Victim is so powerful is because there are advantages to defining oneself as a chronic sufferer. For example, you get God's attention; he chooses you and then is both your Rescuer and Persecutor of your enemies. Also, as a chronic Victim, or sufferer, you can back off many legitimate as well as illegitimate attackers by labeling them “Persecutors,” the second position in the Drama Triangle. Whenever we play the blame game, that is, shifting responsibility from ourselves to the Deep State, rioters, Antifa, the Alt-Right, Trump, Arabs, Jews, Terrorists, Russia, China, the Fed, the “economy,” bad luck, our parents, or the dog that ate our homework, we are defining the meaning of suffering as success in playing the role of Victim in the Drama Triangle. This is the simplest and most common meaning of suffering, and we can almost say it is a pathology embedded in human nature itself. The second prosaic meaning of suffering is as a tool to teach and maintain justice. This meaning has the benefit of justifying violence and the role of Persecutor in the Drama Triangle. God makes you suffer because you need pain in order to grow. In this formulation, we easily see how Persecutors rarely define themselves as such. The vengeful God of the Old Testament wasn't a Persecutor when he was killing all those Caananites, he was rescuing his Chosen People. Bush wasn't torturing Arabs and Iraqis and Afghanis in particular; he was bringing democracy to the Middle East. The meaning of suffering is freedom, democracy, and justice, even when it is wrapped in barbarity. If you see rational contradictions here or your tender sense of morality is offended, it is only because you do not see the noble intentions of all Rescuers everywhere. Rescuers are “only following orders” (see Nuremberg) or making the world “safe for Democracy,” (Wilson). Persecutors only make you suffer for your own good and under their authority as parent, boss, president, vicar of Christ, or guru. Psychologically, the meaning of suffering is life within the tender jaws of the Drama Triangle. If you play one role, you play them all. To pick on Judaism again, to define oneself as a Victim means to refuse to acknowledge or take responsibility for the abuse and Persecution you do, because you see yourself as Rescuing your tribe and following God's commandments. A similar formulation exists for Arabs, terrorists, Lloyd Blankfein, who, as presiding over one of the most predatory of all financial institutions, Goldman Sachs, sees himself as “doing God's work,” as do most US Presidents, historical monarchs, and world leaders. The meaning of suffering for these people is the realization of the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth through their acts as instruments of the divine. If you and I experience it as suffering it is because we do not understand the sacred and divine plan that is being implemented. For example, Arjuna, in the Bhagavad Gita is coached by God (Krishna) to be a Persecutor, in this case, an actual murderer, by convincing him that he is actually a Rescuer in God's sacred Drama Triangle. Problems arise with the awareness that nature does not do drama. Nature is amoral, not immoral. Life itself does not have a moral sensibility. Nature does not experience itself in the roles of Victim, Persecutor, or Rescuer, although persecution and victimization exist everywhere in the natural realm. Suffering as a natural act is amoral and has an entirely different meaning from suffering that occurs as the result of human agency, within the context of social norms. And even then, those have to be subdivided between acts that occur within the Drama Triangle and those that do not. A way to further understand this psychological distinction in the meaning of suffering comes from Transactional Analysis, the form of therapy that originated the concept of the Drama Triangle. 'Games” are defined by Eric Berne as manipulative psychological transactions that contain crooked, hidden motives, involve a “switch,” and a “payoff,” in which one side is rewarded and another generally, but not always, punished or disadvantaged. Berne described a game as an ongoing series of ulterior transactions that lead to a predictable outcome. Ulterior transactions are complex interactions that involve more than two ego states and send a disguised message.The essential feature of a game is its culmination, or payoff, and the principal function of the preliminary moves is to set up the situation for this payoff, which is generally a validation of our world view and sense of self. If we are anchored in the role of Victim, then games will validate that world view as abused sufferer. If we are invested in the role of Persecutor, then games will prove that we are right and everyone else is wrong and the meaning of suffering will be triumph over evil and ignorance. If we need to see ourselves as Rescuers, games will validate our self-sacrifice and noble intentions and the meaning of suffering will be to prove our moral rectitude. While Berne believed games are played as substitutes for intimacy, which everyone wants but few know how to attain, it seems to me that it is more likely games, including those validating suffering as meaningful, are played in order to justify our life script, identity, and world view. He notes, “It is not difficult to deduce from an individual's position the kind of childhood he must have had. Unless something or somebody intervenes, he spends the rest of his life stabilizing his position and dealing with situations that threaten it: by avoiding them, warding off certain elements or manipulating them provocatively so that they are transformed from threats into justifications.” In this model, following Buddhism, Gnosticism, and most wisdom traditions, you are a Victim of your own ignorance and therefore needlessly Persecute yourself and perceive others as Persecutors when they are convinced they are themselves relatively enlightened Rescuers. Or, you view your ego ideals, those who you put on a pedestal, as Rescuers, thereby setting yourself up for betrayal when they fail to live up to your unrealistic expectations. They then become Persecutors in your mind and you are a Victim. You may respond by using your perceived Victimization as justification for Persecuting them. This is a dance Wilber does with both his fans and his detractors. The meaning of suffering, in this case, is ignorance of how we remain lost in the Drama Triangle and our inability or unwillingness to get out. This state exists independent of level of development, enlightenment, or advancement on the cognitive or line of spiritual intelligence. The solution is to learn to continuously ask, “If I were in the Drama Triangle right now, what role would I most likely be in?” For example, my answer for myself at this moment would be “Rescuer, both of myself and my readers.” Once we become aware of this possibility, the next step is to ask ourselves, “What could I do right now that would be most likely to shift me from the role of Rescuer to that of a neutral party or a helper?” In my case it is to be clear on my intention (to state my perspective as clearly as possible) and realistic in my expectations (I am unlikely to change your mind or win your approval). Also, I have to remind myself not to take it personally when others respond to me from this or that role in the Drama Triangle. That is their decision to suffer, either in or out of awareness, and I do not have to join them by taking a complementary role in their game. Both theodicy and nihilism are generally games played within the Drama Triangle, whether in relationships, organizations, or between nations.[4] From a psychological point of view, the best thing we can do to reduce unacceptable suffering and give what suffering that does exist in the world positive meaning and value is to not contribute to it, which means to stay out of the Drama Triangle ourselves. This via negativa, telling us what not to do instead of providing a positive formulation, like “love everyone, including yourself,” “seek inner peace;” “become enlightened,” etc. is more realistic, because positive formulations easily feed into the role of Rescuer and denial of the harm we inflict. Questioning our own motives and intentions and aspiring to some variety of honest, not postured humility, is at least an honest attempt to not contribute to suffering while neither denying its reality nor avoiding it and its consequences. Social justice games are played from within the Victim/Rescuer roles within the Drama Triangle. When we rationalize or justify the suffering of others we are in the Rescuer or Persecutor roles of the Drama Triangle. When we rationalize or justify our own suffering we are likely to be in the role of Victim because we are defending our intentions. We need to recognize them as such, call them out, and refuse to play, which we do when we take a complementary role. This is the role that law is supposed to play. I use “supposed,” because it is evident that law is very commonly and easily co-opted to be a tool for persecution by Persecutors who identify themselves as either Rescuers or Victims, or both, be they police, military, courts, lawyers, wardens, guards, or anyone associated with the criminal justice system. McElroy notes, To use Spiral Dynamics, traditionalism (blue) feels the need to replace the power view (red) because it causes too much violent suffering; modernism (orange) critiques traditionalism because its lack of freedom causes suffering for too many; postmodernism (green) loathes modernism because of the awareness of the suffering it still causes (class, race, sex, gender, ableism, etc.) Reframing the above in terms of the Drama Triangle, red power, traditionalism, and post-modernism need to be critiqued in terms of immersion in the Drama Triangle or freedom from it. The default assumption should be that we and all others are in the Drama Triangle, regardless of our level of development, until proven otherwise, and it is not to be assumed that someone at late personal or vision-logic is less likely to be in the Drama Triangle than someone at mid-prepersonal. What level of development was Obama at while President? Was he out of the Drama Triangle? Did he play it less or simply more skillfully due to his high level of development on multiple lines? Are gurus free of drama or are they simply more skillful players of the game? Idealized others are likely to be more powerful conduits of suffering than their less enlightened brethren. Integral and theodicyThe question of suffering, so central to humanity, has largely been sidelined by Integral. My own answer to why this is so is that for Integral, the cognitive line leads, which means that questions of epistemology and ontology take precedence over issues of morality. These priorities are implied by McElroy: the problem of suffering makes us to understand that the ultimate question, contra Leibniz and Heidegger et al, is not “why is there something rather than nothing?” nor even the penultimate question “why is there this something rather than something else?” but instead the question “why does this something hurt so much? This creates uneasiness for both knowing and being because epistemology doesn't know the answer to evil and ontology experiences it as a direct threat to its very existence. Another problem is that evil is a moral question, and morality creates great problems for our self-image, our identity, and our conceptions of human development. To take theodicy seriously risks upsetting the Integral apple cart. (Actually, it is more of a bodhi cart that gets upset.) Theodicy, which deals with the existence and reasons for evil, places morality front and center for both collective and personal development. Wilber's response to the problem of suffering appears to be closer to that of Whitehead and his process philosophy: “the world is not a collection of thing-like (ontological) essences but of existential processes,”... “the One and the Many and the creative advance into novelty”...”working themselves out through interactions of parts and wholes...” Wilber also shares the assumption of process theodicy that the universe is panentheistic, that is, both believe that God/Spirit contains the universe/existence but exists beyond them as well. How does Integral semiotics, that is, looking at ourselves and life from first, second, and third “I,” “We,” and “It” perspectives, reduce suffering? We can and do function within the Drama Triangle equally well from all three perspectives, however, it can help us clarify the meaning of suffering. While Persecution of “Its” may be the most obvious example of suffering and Rescuing of “I” and “We” most likely responses to suffering, we are all self-persecutors to the extent we stay in drama and we conspire through cultural groupthink scripting to maintain our roles in the Drama Triangle. Victimization imposed by necessity from the “It” realm does not require a conclusion of meaningless suffering. It's up to us what value or meaning we are going to project onto suffering from the interior collective quadrant of hermeneutics and culture. That is a core human responsibility, perhaps THE core human responsibility. Nobility and honor in the face of suffering is not an easy ask, but it is not an impossible one. The three roles of the Socratic Triune, the Beautiful, Good, and True can be associated, as Wilber has done, not only with the “I,” “We,” and “It” realms, but with the roles of Victim, Rescuer, and Persecutor. The Persecutor believes he represents truth because he means well; he is certain that when he attacks it is in the name of justice. The Rescuer is convinced that he or she represents the good, love, compassion, and enlightenment, because “I am only trying to help.” Never mind that I did not ask if help was needed, did not check to see if the “help” I was giving really was helpful, and I did not stop “helping” when the job was done. The Victim is convinced that they are innocent and simply want peace and harmony and to be left alone. That position can be summed up as follows: Way down yonder where the tall grass grows Who is the victim and who is the persecutor is a matter of perception; when perception happens within the Drama Triangle, suffering, even when created naturally or accidentally, becomes Suffering, or avoidable, manipulative, and exploitative. McElroy shares excerpts from an interesting and insightful dialogue between Wilber and Marc Gafni on Theodicy and the nature of good and evil that clarifies how Integral approaches suffering. Here is one of Wilber's comments: Now, as God in particular is also evolving and starting to be understood, versions of Spirit from all three perspectives, first person and second person and third person, then activity that keeps me away from Spirit in first person is activity that keeps me away from my own highest and truest Self. So it's activity where I am, in a sense, not being true to my deepest Self which is also the deepest self of the Kosmos at large. And so the basic activity that does that is the self-contraction or the Separate Self sense, or the breaking apart of awareness into subject or object or a seer and a seen, knower and a known. That throws me into the world of the pairs [dualism], throws me into good and evil, and in a certain sense opens me to an experience of unpleasant evilness, as it's also opening me to an experience of relative goodness. Both of these are only relatively real. Neither of them have any ultimate reality, but what's generating the whole thing is the activity of self-contraction, of the Separate Self. So what both Job and Nagarjuna have in common is the discovery of that deeper being, and that discovery is what is known with a certainty.[5] To get the full flavor of the interview and the perspectives on good and evil of both participants, I recommend you read McElroy's account in his essay. However, just this brief excerpt serves to highlight several problems. The first is that their answer, finding your true, unique self that transcends suffering, is a spectacular non-answer, a major shifting of subject from that of suffering to “suffering is not real if you simply adopt our enlightened perspective.” If you find that audacious and grandiose, you are not alone. The second problem is that it is dismissive, in that it fails to take the reality of suffering seriously. Instead, your suffering is mere delusion. The third problem is that this analysis is cruel, because it offers an unattainable absolute as a solution to a very real day-to-day issue we all experience. The conveyance of cruelty is generally done from the position of Persecutor in the Drama Triangle even when it is wrapped in the sanctimony of an enlightened Rescuer. The fourth problem is that the implication is that these two very bright individuals, who have undoubtedly had multiple amazing mystical experiences, have transcended suffering, which is, of course, a deception if not an outright lie. The fifth problem is that they both have track records that diminish their authority as dispensers of enlightenment regarding what is evil and what is not. But we are asked to overlook or better, simply ignore, perhaps out of ignorance, such problems and have faith that the Holy Grail of freedom from suffering is within our reach, if we will only take their teaching to heart. As I read that dialogue between Wilber and Gafni on theodicy for the second time, the image came to mind of them wildly veering downward in Griphook's cart, plummeting into the depths of Gringott's (A scene out of Harry Potter): Griphook whistled and a small cart came hurtling up the tracks toward them. They climbed in -- Hagrid with some difficulty -- and were off. You can decide who exactly Griphook represents, but in any case, their destination, the Vault of the Heir of Salazar Slytherin, is probably not exactly what we signed up for when we got on board the Integral Express. In other words, Griphook is not taking us to enlightenment, salvation, beyond good and evil, or to the extinction of suffering. He's taking us deeper and deeper into the Drama Triangle. Why? These guys are basically saying, “If you just become enlightened, like we are, then you will resolve the paradox of evil.” If goes without saying that until you do, you will remain victimized by suffering, but of course that is your choice. You can either listen to us and transcend and include or you can remain a goat, in outer darkness, where there be dragons...” McElroy also draws our attention to Wilber's distinction between evolutionary and involutionary givens and their relationship to theodicy. Here is how Wilber formulates the distinction: Still, these blindingly brilliant, philosophical avatars of Eros saw one, overwhelming, awe-inducing fact: Spirit is your own Original Face. It is not something that is socially constructed, or that is created for the first time when you happen to stumble upon it, or that pops out at the end of a temporal sequence, or that is nothing but some sort of Omega that can only be realized at the end of the universe. Spirit is your own ever-present, radically all-inclusive, always-already-the-case-reality, which is why some notion of involution, or return to a Spirit that was never lost, is an inescapable part of the theoria of every great philosopher-sage, bar none. There is one, staggering, screamingly undeniable involutionary given: the ever-present Ground of all grounds, Nature of all natures, Condition of all conditions… I am not a fan of this distinction between involutionary and evolutionary givens because I don't see how it helps resolve the issue of suffering. In fact, this distinction complicates that discussion. When Wilber says, “...the notion of involutionary givens is a necessary framework with which the human mind, itself a product of evolution, must use in order to construe evolution in a noncontradictory way,” what comes to my mind is that no scientist of evolution that I know of agrees with Wilber on this point. The EES, extended evolutionary synthesis, the current model of how evolution occurs, is extremely broad and encompasses multiple variables that contribute to the evolutionary process, but a priori “givens,” that stand apart from evolutionary processes themselves, is not one of them. Wilber's distinction harkens back to the realist and nominalist debate in the Middle Ages, which is a direct descendant of Plato and Aristotle's difference of opinion regarding eternal, pre-existing Forms or Ideas and individual elements that have no independent, pre-existing essence. The nominalists, represented by people like John Scotus and William of Occam, won the debate for the same reason that science continues to circumscribe idealism: observation and data that can be confirmed by consensus is on the side of particulars. It should also be pointed out that the entire idea of philosophical rationalism, based as it is on a priori existing axioms, has been pretty well put to bed or, to be less kind, had final unction muttered over it, by George Lakoff and others, who show that a priori axioms are arbitrary assumptions which, once assumed, can create a wide variety of internally consistent world views. A belief in this or that set of a priori axioms has been called “the power law religion,” after the belief that pre-existing patterns repeat in nature according to mathematical powers, as fractals and scale-free networks.[8] Edward Berge explains: So what is the root of this religion? Holme nailed it when he said the power law universally applies “in the Platonic realm.” This is a long-held, guiding myth that has remained strong in math. Lakoff and Nunez (2001) dispel this myth, noting that there is no proof of an a priori mathematics; it is purely a premised axiom with no empirical foundation. Just like the conception of God it is religious faith. We can only understand math with the mind and brain, so it requires us to understand how that brain and mind perceives and conceives. Hence there is no one correct or universal math. There are equally valid but mutually inconsistent maths depending on one's premised axioms. This is because math is also founded on embodied, basic categories and metaphors, from which particular axioms are unconsciously based (and biased), and can go in a multitude of valid inferential directions depending on which metaphor (or blend) is used in a particular contextual preference. They dispel this myth of a transcendent, Platonic math while validating a plurality of useful and accurate maths.[9] “Givens,” whether involutionary or evolutionary, are a priori axiomatic premises that have to be identified and confirmed with data. A phenomenalistic approach to the question of theodicy tables such premises and assumptions in order to clearly what exists without such human projections onto experience. It is for similar reasons that I have difficulty with Wilber's analysis of relative and absolute purpose. Clearly, the entire issue of theodicy, “Why is there evil?” Implies a purpose, which is a desire to get rid of suffering. Wilber's solution is to become one with a state that transcends the seeking after a solution, which is what relative purpose amounts to: Purpose means that you want to get from now which is lacking something to a future which has found that missing something. And the drive to get that missing something is purpose. But the ultimate, the absolute has nothing lacking, nothing missing…There is nothing that is outside you and therefore desire as such simply ceases to exist as any sort of agitated drive or need. And purpose likewise tends to evaporate because at this deepest level of reality you are already one with absolutely everything that arises or that will arise… So in this state of oneness where I do not feel the earth I am the earth, and I do not watch the clouds I am the clouds. And in that state I do indeed love the mountain, and I love the earth, and I love those clouds. But in the same awareness I love global warming, I love toxic pollution, and I love terrorist attacks, I love murder and I love crime, and I love deadly accidents, and I love my own faults and I love the evil in you and I love hatred wherever I see it. All-inclusive means all-inclusive… The only way you can get the infinite with its radical and ultimate great perfection to manifest in this relative limited finite world is to have each finite thing agitate to become infinite, to become more unified and more whole, to be one with spirit itself, to return to its own source and ground.[10] The question that immediately and obviously arises is, do you and I want to love terrorist attacks, murder, crime, and deadly accidents? What exactly is that sort of love? I would suggest that it is a love that is exclusive of the lower left quadrant, of exterior collective relationship, because it is impartial, completely without preferences, and no longer in the moral realm. While Wilber might argue that it is “trans-moral,” functionally, how is that different from amoral? Might we be looking at an elevationistic version of the Pre/Trans Fallacy, in that what is prepersonal, morally pre-pre conventional, and amoral is declared to be transpersonal, post-post conventional, even while plenty of evidence exists that Wilber and other idealists are acting within the boundaries of relationships that are governed by social norms? As long as this is the case, on what grounds can we profess that we have accessed or live in a state that transcends suffering? This is quite the ask, like getting people to not only adopt, but enjoy eating meal worm and ground grasshopper burgers. Yes, it is theoretically possible, but then, so is Gringott's bank. When we approach Integral from the perspectives of both theodicy and the Drama Triangle, the basic game structure appears to be, “I will Rescue you by giving you a multi-perspectival, vision-logic, integral aperspectival world view and level of cognitive development, with which you will identify, making you second tier. When enough of you are Rescued, say 10%, society will reach a tipping point and we will all hold hands around the campfire and sing “Kum-ba-ya.” Further, if you will only meditate, you will reach non-dual Turiya, or perhaps even better, Turititya, and become enlightened, in which state you will Rescue yourself by transcending theodicy and the problem of suffering.” The Drama Triangle does indeed give purpose to suffering. The problem is, that purpose itself generates more suffering. Moral implications of theodicyI mentioned earlier that there are moral as well as ontological implications of suffering that undermine the transpersonal, the home ground of the spiritual. This is because it is difficult to generate a legitimate definition of “spiritual” that doesn't include and imply morality. Because spirituality claims to exist in all four quadrants and not simply in the interior individual quadrant of consciousness, where mystical experiences of oneness and the sacred occur, we are inevitably confronted with what spirituality means in the exterior collective quadrant of relationships and, in particular, how our spirituality is perceived by others. For example, if your intention is to do good but your actions are experienced as causing suffering or evil, who is right? An integral approach would be to come up with a conclusion similar to that regarding the Blind Men and the Elephant: each is partially correct and each is partially wrong. However, because individual holons are embedded in collective, social holons, individual behavior must yield to the determinations of the social norms of the collectives in which they are embedded. Wilber acknowledges this reality in Integral Spirituality when he notes that the breadth and depth of enlightenment is conditioned by the width and breadth of the collective of the age into which we are born. Therefore, for example, the width and breadth of our potential for enlightenment is greater than that of Bronze Age masters, such as Buddha, Jesus, and Shankara. This subordination of our moral intent to collective moral norms exists apart from questions of justice or fairness; yielding personal moral certitude to the conclusions of collectives can be both highly unfair and unjust. There are, in addition, also occasions where the will of the collective is egocentric or sociocentric and where adherence to personal worldcentric ethical behavior is the moral choice, regardless of what the collective says. The great lights of non-violence, including Thoreau, Gandhi, King, and Mandela provide powerful examples of suffering transcended by worldcentric moral cause. Fortunately, there are guidelines to navigate through this thicket. We can ask, “Is my behavior respectful of the expressed wishes of those it affects?” “Is it reciprocative, meaning, am I not doing to others what I wouldn't want them doing to me?” “Is there an equivalence in value exchange?” “Am I being trustworthy in terms of the social norms I have agreed to live by?” Am I being empathetic, that is, do those affected by my actions agree that I understand their perspective whether or not I agree with it?” These are worldcentric standards of moral behavior, in that they represent social norms likely to be held by all groups and individuals, regardless of their level of development. Even highly narcissistic individuals want these conditions to apply to them. They are super-ordinate in relationship to the license bequeathed by the radical freedom of transpersonal states, because those are interior individual quadrant freedoms, meaning they are not accountable to any collective and therefore do not have to meet the criteria of the exterior collective quadrant, required for moral tetra-mesh. They may extend into the interior collective and exterior individual quadrants, but no holonic morality exists if it does not also satisfy conditions of interpersonal exchange in the exterior collective. This is where most leaders and gurus fail the test of morality, create suffering, and disqualify themselves from some universal characterization of spirituality. Mike McElroy addresses this issue when he writes, Integral in its desire to include all valid paths of experience (“everybody's right”) can sometimes be in danger of justifying suffering that should not be justified. Integral can fall into a kind of Hegelian compromise justifying the general/universal trends and losing sight of the horrendous suffering of individuals and smaller groups. That is when theodicy can actually be an evil in itself. Gurus and integralists, even under such conditions, can still be considered spiritual on this or that particular line, such as in their grasp of spiritual concepts or access to meditative states of oneness, but again, just what exactly is spirituality without morality? In terms of theodicy, it would be power, omnipotence, and wisdom, omniscience, without goodness, omnibenevolence. Along with religionists and New Agers , the burden of proof is upon Integralists to show how and why both theisms and the concept of spirituality do not contribute to the problem of theodicy rather than simplify, reduce, or resolve it. While a deity-free notion of spirituality reduces the blatancy of the dilemma, we have seen how it remains with concepts of consciousness, the divine, and spirituality. They offer no solution to the problem of suffering. In addition, due to the intrinsic association of spirituality with morality, spirituality sets up expectations that are unrealistic and easily lead to disillusionment, its own variety of suffering. Due to these factors, a sacred humanism provides a much more satisfactory answer to the question of the meaning of suffering. One can still worship nature, have all sorts of mystical experiences, indulge in whatever sacred rituals are attractive, while emphasizing both responsible relationships and personal enlightenment. The higher we fly, the farther we transcend the norms of our collective, the farther we have to fall and the harder the landing is likely to be. Therefore, it seems wise council to strive for excellence, but above all to strive for excellence in the ability to achieve and maintain balance, particularly on the core moral line. Working at recognizing and staying out of the Drama Triangle is a useful, practical daily yoga to that end. NOTES[1] Bertalanffy, Lv., General System Theory (1968) - 8. The System Concept in the Sciences of man, p. 191. [2] Faulkner, R. The Second Law of Thermodynamics and the Curse. Answersingenesis.org. [3] Bertalanffy, Lv. General System Theory (1968) - 8. The System Concept in the Sciences of man, p. 192. [4] The Drama Triangle is found in other dimensions as well. See Dillard, J., (2017) Escaping the Drama Triangle in the Three Realms: Relationships, Thinking, Dreaming. Berlin: Deep Listening Press. [5] Wilber, K., Ken Wilber and Marc Gafni on Evil. https://centerforintegralwisdom.org/ [6] Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone Chapter 5, Diagon Alley [7] From footnote 26, "Excerpt A: An Integral Age at the Leading Edge" from Wilber's eternally forthcoming volume 2 of the Kosmos trilogy [8]Berge, E. (2019) The Root of the Power Law Religion, IntegralWorld.Net. [9] Berge, E. (2019) The Root of the Power Law Religion, IntegralWorld.Net. [10] Wilber, K. “Integral Purpose.” YouTube. Cited in McElroy.

|