|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992). David Christopher Lane, Ph.D.

Professor of Philosophy, Mt. San Antonio College Lecturer in Religious Studies, California State University, Long Beach Author of Exposing Cults: When the Skeptical Mind Confronts the Mystical (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1994) and The Radhasoami Tradition: A Critical History of Guru Succession (New York and London: Garland Publishers, 1992).SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY DAVID LANE It's a Matter of FocusConfusing Practicality with FaithDavid Lane

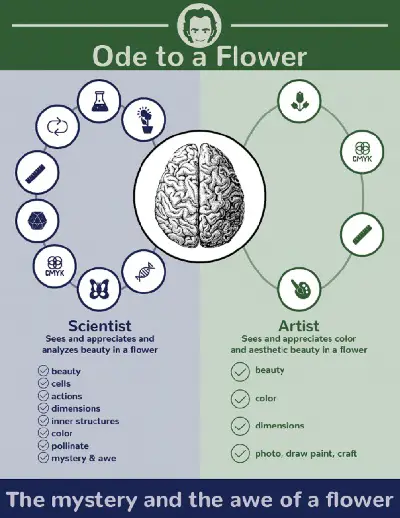

INFOGRAPHIC BY RACHEL STELZER

This isn't scientism and it isn't anti spirituality. It is called being practical.

I appreciate that Steve Taylor has taken the time to respond to my recent essay entitled "Understanding Matter" [see "Misplaced Faith"]. As this will be my 150th article for Integral World, I find it appropriate that it will concentrate on why I have long championed being skeptical when it comes to paranormal claims. This is not because I have an a priori belief that the supernatural is non-existent, but only that the surest pathway to discover that which is lies beyond physics and the other sciences is to let those disciplines fully and patiently attempt to explain such phenomena first. If we don't do such, we run the very real risk of accepting sleight of hand magician tricks as miracles, as was the case with the infamous Sathya Sai Baba who deceived thousands with his amateurish conjuring. 1First, Steve Taylor makes a fundamental error when he writes, “He [Lane] suggests that this makes science superior to spirituality.” I have never argued that science is superior to spirituality precisely because I view them as two distinct processes. I hold that a meditating physicist is not a contradiction in terms. 2

The reason science has been so successful is precisely because it has “real” explanatory ability.

Second, Taylor argues that he “revere[s] science, and [I] am an enthusiastic advocate of the scientific approach.” Yet he betrays that very sentiment just a line or two later when he writes, “in order to have any real explanatory ability, science has to unmoor itself from a materialist perspective and adopt a spiritual one—specifically, the idea that the essential reality of the universe is not matter, but consciousness.” This is a confusing juxtaposition, since science is a practical endeavor, as I have stated repeatedly in a number of articles (including my original critique of Taylor), and it is because of this (and not some absolute metaphysic) that the focus has been on material causes and correlations. The reason science has been so successful is precisely because it has “real” explanatory ability. If it didn't nobody would use it nor would we see anyone advocate its use. Even non-scientists understand how successful science has been because they can literally see and interact with its magnificent technological by-products. We can provide innumerable examples of why science's method of looking at the empirical world works—from heart and kidney transplants to space rockets to the moon and beyond to the development of electricity and solar power. None of these endeavors needed a “spiritual” perspective to work. Therefore, I find Taylor's lament in this regard short-sighted since to acknowledge the greatness of science is to realize that it has made such tremendous progress by not getting bogged down with antiquated and unnecessary religious mythologies. 3Third, Taylor fundamentally misunderstands the very intention of my earlier article when he writes, “The fact that Lane continuously assumes that I am criticising science as a practice—when in fact I'm just criticising materialism—shows that, in his mind, science is synonymous with materialism. This is a serious philosophical error.” No, I have not made that mistake of believing that “science is synonymous with materialism.” Quite the opposite, since I have argued that it is a practical process and doesn't have to forever tie itself with an overarching metaphysic. I am not the one arguing that science lacks explanatory power because it has “to unmoor itself from materialism.” Taylor, not me, is the one who has a problem with science's focus on matter and what it portends. Yes, science is a method and therefore it doesn't need an agenda of “spirit” to make it more powerful. Science doesn't “explain away” psi but rather attempts to better understand all the possible ways it could happen without resorting to supernatural explanations. This is how it should be because otherwise we end up accepting the silliest of parlor tricks (like “bending spoons” with our minds) as being beyond rational explanation. We are not skeptical enough. For example, if Uri Geller or others really do have the ability to bend spoons merely by thought (and not by purchasing easily bendable metals beforehand) then the more we doubt and test them the greater their respective abilities will shine forth. The same hold true for any so-called paranormal phenomena. No need at this stage to usher in spirit when simple physics can upend bad magic tricks. 4Fourth, Steve Taylor indulges in a completely inaccurate exaggeration when he categorically claims, “Scientists have made no progress in understanding 'rogue' phenomena like near-death experiences, psi phenomena like telepathy or precognition, or even consciousness itself.” To the contrary, science has made tremendous progress on each of those fronts, even if many mysteries still persist. Take psi as a good example. Is the field worse or better off because some scientists have been hyper critical of how many previous tests were conducted without proper double-blind protocols in place or that faulty statistics were employed? Does this mean, by extension, that such scientists are caught in web of blind materialism? No, quite the opposite, since by demonstrating where and when a particular study is insufficient they help future researchers avoid unnecessary data traps. As Persi Diaconis, Mary V. Sunseri Professor of Statistics and Mathematics at Stanford University, wisely summarizes in his Statistical Problems in ESP Research: In search of repeatable ESP experiments, modern investigators are using more complex targets, richer and freer responses, feedback, and more naturalistic conditions. This makes tractable statistical models less applicable. Moreover, controls often are so loose that no valid statistical analysis is possible. Some common problems are multiple end points, subject cheating, and unconscious sensory cueing. Unfortunately, such problems are hard to recognize from published records of the experiments in which they occur; rather, these problems are often uncovered by reports of independent skilled observers who were present during the experiment. This suggests that magicians and psychologists be regularly used as observers. New statistical ideas have been developed for some of the new experiments. For example, many modern ESP studies provide subjects with feedback-partial information about previous guesses-to reward the subjects for correct guesses in hope of inducing ESP learning. Some feedback experiments can be analyzed with the use of skill-scoring, a statistical procedure that depends on the information available and the way the guessing subject uses this information. Yet despite Persi Diaconis's cautionary notes, he believes the field of parapsychology is an important one and shouldn't be neglected. In his concluding paragraph he writes, “To answer the question I started out with, modern parapsychological research is important. If any of its claims are substantiated, it will radically change the way we look at the world. Even if none of the claims is correct, an understanding of what went wrong provides lessons for less exotic experiments. Poorly designed, badly run, and inappropriately analyzed experiments seem to be an even greater obstacle to progress in this field than subject cheating. This is not due to a lack of creative investigators who work hard but rather to the difficulty of finding an appropriate balance between study designs which both permit analysis and experimental results. There always seem to be many loopholes and loose ends.” So, has the field of parapsychology improved because of such skepticism? The answer is a clear yes and underlines the very point I have been making all along. By focusing on a more rational and physicalist explanations for a given psi occurrence, it provides a portal for positive experimental results that, if viable, can robustly resist falsification. A good example of this can been seen in how various ganzfeld experiments have been conducted after critical scrutiny by such skeptics as Ray Hyman. Even, a pro-psi advocate, such as Dean Radin, admits “Most of the [auto]ganzfeld experiments took advantage of lessons learned in past psi research, thereby avoiding many of the design problems discovered by early experimenters.” Hence, it is not a question of science's alignment or non-alignment with an overarching philosophical purview, but rather that by focusing on the empirical arena as a starting point it can better differentiate that which is materially generated (or contextualized) from that which is supernatural. Otherwise, we can be caught in an intractable web of mistaking that which is pre with that which is trans. 5

Fifth, contrary to popular misunderstandings, even critical tomes on the paranormal will popularize where and when certain psi results suggest something extraordinary is transpiring. For instance, in my Critical Thinking courses we have used a textbook entitled How to Think About Weird Things which speaks positively about current research in ganzeld experiments, going so far as to argue that, “The ganzfeld procedure remains the most promising way to demonstrate the existence of psi. Bern and other well-respected psychologists remain convinced that these studies identify an anomaly that has not yet been adequately explained. A well-controlled ganzfeld experiment may well turn out to be replicable. If it does, we may have to begin changing our worldview.” This is commendable and shows that despite Taylor's protestations to the contrary science is not amiss to discovering features to the universe which betray physicalism as we presently understand it. Indeed, I would argue as I have in the “Remainder Conjecture” that by fully exploring the physicality of any given event will by that very procedure show us the limits (if there are any) of that line of inquiry. The history of science, of course, is replete with such examples, ranging from Werner Heisenberg's 1927 principle of uncertainty in quantum mechanics to Kurt Gödel's 1931 incompleteness theorem to Alan Turing's 1936 proof that an all-purpose algorithm cannot solve the “halting problem” for all “possible program input-pairs,” to the Cubitt, Perez-Garcia, Wolf 2015 mathematical proof that shows the spectral gap problem for “families of quantum spin systems on a two-dimensional lattice with translationally invariant, nearest-neighbour interactions” are fundamentally undecidable. 6

The very reason scientists have tended to look for physical causes and correlations is because it produces practical and usable results.

Sixth, Taylor tends to use straw person (or what I previously called bogey man) arguments when he misleadingly claims “Materialism does not, and should not, have a monopoly over science as a practice.” Science is a free enterprise and no one is restricting anyone from doing the method. Taylor apparently keeps forgetting my central thesis is that the very reason scientists have tended to look for physical causes and correlations is because it produces practical and usable results. Taylor and other of like mind are free to do consciousness first research. Who exactly is holding them back? In this regard, there are a number of eminent thinkers who have taken a consciousness-first approach, such as Donald Hoffman at the University of California, Irvine. My wife Andrea Diem, who also did pioneering brain research with V.S. Ramachandran at the University of California, San Diego, even wrote a brief article ["The Hoffman Conjecture"] outlining his approach. Dr. Diem wrote, Although significant progress has been made in the past thirty years the sticky problem of “qualia”—what Chalmers calls the hard problem—is still a Gordian knot that has yet to be unraveled. While many neuroscientists are attempting to reverse engineer the brain and develop simulation models of how a set of 86 billion neurons could be responsible for generating self-reflective awareness, other maverick scientists have taken a much more radical approach by arguing for a consciousness-first principle, similar in some ways to the argument posed by Ramana Maharshi and Advaita Vedanta. Yet, the key here again is one of practicality not propping up a metaphysical agenda. Hoffman wants his theory to be falsifiable which means that he could simply be wrong. That is the way of scientific progress, whether or not one has a spiritual or atheist agenda. 7

I like to see if I can possibly understand a bit more about myself and the universe given the short duration we have on this planet.

Seventh, Taylor seems to forget his own word usage and rhetoric when he lambasts me for employing the word “rogue” when he writes, “Even Lane's use of term 'rogue' is telling. These phenomena are only rogue from the standpoint of materialism. They are only rogue because they contravene the assumptions of materialism. Lane's use of this term shows that he has already adopted materialism as his default metaphysical position and classifies phenomena according to whether they are acceptable in terms of its assumptions.” Taylor neglects to remember that he, not me, was the one who first used such a descriptive term in his previous essay when he wrote, “On the one hand, there are a wide range of 'anomalous' phenomena that it cannot account for, from psychic phenomena to near-death experiences and spiritual experiences. These are 'rogue' phenomena that have to be denied or explained away, simply because they don't fit into the paradigm of materialism, in the same way that the existence of fossils doesn't fit into the paradigm of fundamentalist religion.” I therefore used the term “rogue” in my follow-up essay exactly because it was a term that Taylor himself employed. Now, ironically, I am being called on the carpet for the term as if I were somehow intimately agreeing with it and thereby siding with a materialism only stance. This is not only a bit ridiculous, it is disingenuous on Taylor's part. Let me state it very simply once again since it bears repeating. My default position, in contradistinction with Taylor's misreading, is not one of metaphysical materialism. I don't hold such a view since that assumes far too much. No, rather I have a practical bent which argues that we should fully explore and exhaust physical explanations first when attempting to explain the world at large. Does this by extension mean that only physical things and physical explanations exist? Not in the least, but it does show a pathway where we can better understand how certain phenomena (like waves and like stars) behave the way they do. I have already confessed my deepest metaphysic in a series of books and articles and it is one, I suspect, I share with many others. What is that? I don't know much and in that unknowingness I like to see if I can possibly understand a bit more about myself and the universe given the short duration we have on this planet. In this regard, I feel a kinship with Socrates, Lao Tzu, and Nicholas of Cusa, who each professed to a radical unknowingness and how this in turn led them to a free and open inquiry of reality. Hence, it is for this very reason that I think we are better served by letting science look to physics and chemistry and biology first. Not because they are the only worthy disciplines, but because they can by their very scrutiny clear away the unnecessary shrubs of magical thinking by closely scrutinizing what can and cannot be known about the cosmos that surrounds us. 8 Christof Koch: “No brain, never mind.”[2] Eighth, I find it rich with irony that Steve Taylor will cite Christof Koch's work on consciousness because he has [claims Taylor] moved away “from reductionist physicalist explanations.” Actually, Koch confesses that he is a “Romantic Reductionist” and even titled his autobiography[1] with that same moniker, explaining an interview that “I'm a reductionist because I do what scientists do. I take a complex phenomenon and try to pull it apart and reduce it to something at a lower level.” Koch is currently the president and chief scientific officer of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle. The main aim of this organization is explained in their vision statement, “Understanding what makes us human is no small task. We are beginning with three primary areas of focus: Deciphering how information is coded and processed in the brain; Unraveling the codes within cells that govern their identity and function; and Characterizing and cataloguing the wide variety of cells that constitute the brain.” I applaud these efforts since I think they will unravel much of the mystery behind why consciousness arises within (but not apparently without) neural complexity. On this front, Koch has aligned himself with Giulio Tononi and his theory of Phi or Integrated Information Theory. But this alignment doesn't argue for a soul or a spirit divorced from matter but rather suggests certain forms of complexity in matter give arise to differing levels of consciousness. As Koch elaborates (Nautilus, April 2017[2]) “So you want a brain-based test that tells you if this person is capable of some experience. People have developed that based on this integrated information series. That's big progress. The current state of my brain influences what happens in my brain the next second, and the past state of my brain influences what my brain does right now. Any system that has this cause-effect power upon itself is conscious. It derives from a mathematical measure. It could be a number that's zero, which means a system with no cause-effect power upon itself. It's not conscious. Or you have systems that are 'Phi,' different from zero. The Phi measures, in some sense, the maximum capacity of the system to experience something. The higher the number, the more conscious the system.” When Koch worked with Crick they realized at the very beginning of their collaboration that in order to study consciousness they would need to start with something fundamental but less complex. They chose visual awareness. In a joint paper on the subject they elaborated why, “How can one approach consciousness in a scientific manner? Consciousness takes many forms, but for an initial scientific attack it usually pays to concentrate on the form that appears easiest to study. We chose visual consciousness rather than other forms, because humans are very visual animals and our visual percepts are especially vivid and rich in information. In addition, the visual input is often highly structured yet easy to control. The visual system has another advantage. There are many experiments that, for ethical reasons, cannot be done on humans but can be done on animals. Fortunately, the visual system of primates appears fairly similar to our own (Tootell et al., 1996), and many experiments on vision have already been done on animals such as the macaque monkey.” Again, Crick and Koch realized it was a “matter of focus.” And because of this specific concentration, they succeeded in making much headway, just as V.S. Ramachandran did when working on visual perception and why amputees may feel “phantom pain” in limbs that no longer exist. 9

I don't want to see us get hoodwinked into believing something without sufficient evidence.

Ninth, Taylor wrongly alleges that because I utilized his own terminology that it “shows that he has already adopted materialism as his default metaphysical position and classifies phenomena according to whether they are acceptable in terms of its assumptions. This isn't so different from a religious person who classifies phenomena as good or evil according to whether they accord with their beliefs.” Once again, Taylor confuses a preference for practical results with metaphysical assumptions, overlooking my simple argument that if one really wants to provide evidence for the paranormal that will withstand the onslaughts of reason, then we should make doubly certain not to settle for anything less than overwhelming evidence lest we be naively duped into the process by charlatanism (especially in a field filled with quackery). Does my clarion call for patience and skepticism therefore mean that I believe that rationality is the only method for understanding the world? No, it suggests that I don't want to see us get hoodwinked into believing something without sufficient evidence. In our desire for the transcendental we don't need to rush the proceedings, as if this higher truth is so fragile and tentative that it will disappear if we ask too many doubtful questions of it. There are a number of instructive examples I can cite here, but let me focus on one that I have mentioned before. Baba Faqir Chand was a well-regarded Shabd yoga master who had a plethora of out-of-body experiences and was the devotional object of thousands of satsangis throughout India. He recalls how when he was young and in search of God he had a transformative visionary experience where he saw his future guru, Maharishi Shiv Brat Lal, who provided Faqir with his home address. Faqir was wonderstruck by this mystical encounter and began writing letters each month to the guru and the address he saw in his vision. Ten months later he discovered that his vision was correct and that his eventual guru had received those letters. Eventually Shiv Brat Lal responded, telling Faqir to personally visit him. Now on the surface, this seems like an unassailable illustration of psychic power (telepathy or precognition or whatever label one wishes to enjoin) since Faqir apparently had no foreknowledge about the guru or his residence. Yet, decades later when Faqir realized that religious visions were projections of one's own mind (and were not generated by the religious figure who was objectified) then he started to wonder how and why he saw Shiv Brat Lal when he did and, more pointedly, why he envisioned the correct address for him. Because Faqir allowed himself to doubt the “psychic” nature of his experience he looked for more physicalist and rational explanations for his extraordinary vision. And to Faqir's chagrin, he found out that before this he had his mystical experience it was very likely that he had come upon one of Shiv Brat Lal's many publications which were widely distributed in Hindi and Urdu at that time. In some of those pieces, Shiv Brat Lal's address is listed. Now this doesn't explain away Faqir's vision, but only provides much more nuanced information to better understand how such a numinous encounter could possibly occur without resorting to something transrational. Therefore, it is vitally important, I would suggest, not to succumb to metaphysical theorizing too early if we have not yet done the necessary (and hard) work of thinking of alternative hypotheses which are grounded in what has already been established. 10Tenth, Steve Taylor raises a question that I think is very easy to answer. He queries, “But when do we get the go ahead to apply different metaphysical approaches? At what point do we decide that materialism doesn't fit the bill?” Anyone right now is quite free to apply whatever metaphysical approaches they wish and they are also free to decide that materialism is insufficient. But herein lies the rub: what kind of evidence does one proffer to hold such a position? As Laplace argued long ago and which Carl Sagan later modified, “extraordinary claims demand extraordinary proof.” The scientific community would welcome such amazing news. Bring it on. Who or what is holding anyone back, particularly now when there are open channels of information available worldwide via the Internet and the World Wide Web? But don't expect seasoned skeptics to rush where fools fear to tread, if what is proffered is less than convincing. Also, we should never be discouraged simply because critics demand more and more evidence for a given paranormal claim since that will only help garner more information, not less, which can over time serve as a solid foundation for what was once regarded as pseudoscientific claptrap. 11

There is no need to go metaphysical when we haven't even touched the surface of what can be known physically.

Eleventh, Steve Taylor reveals a certain impatience when it comes to understanding consciousness and NDE's which I find surprising, particularly given how both fields of study are so new. Writes Taylor, “. . . it is time to admit failure and try different approaches. Surely after decades after attempting and failing to explain psi phenomena as fraud, and to explain near-death experiences in neurological terms, it is time to adopt other perspectives.” There is much to unpack here in Taylor's rhetoric. But let me start with the most obvious. There has been massive fraud in those who claim to have psychic powers and we should be thankful that trained magicians, independent scholars, and sharp minded skeptics have exposed these charlatans trying to pass off their cheap parlor tricks for the real deal. So, on this front, we must be uber vigilant not to be taken in by con artists who get cleverer each year in deceiving us with their tricks. Furthermore, the scientific study of consciousness and near-death experiences is a relatively new endeavor, especially given that our technological tools for studying the brain and all its complexity are still in their infancy and are quite crude compared to what they will be in the decades to come. Lambasting neuroscience for not yet fully resolving the mystery of consciousness is akin to critiquing Kepler for not being able to precisely explain the orbit of Mercury. Astronomy back then, like neuroscience today, was in its beginning stages. It takes time for any science to mature and develop more exacting theories that can make predictions that will withstand scrutiny. The brain and its 86 billion neurons are the most complex structure in the known universe (as of yet found) and therefore is it really that surprising that it will take some time to unravel all its subtle interactions? Lest we forget, it is only called promissory materialism because it has in the past (via astronomy, physics, chemistry, and biology) been able to deliver on so many promises in a stupendous way—from unraveling the genome to mapping the known universe. Do we castigate physics today because there are still things like dark matter and dark energy that physicists don't fully comprehend? No. We realize that it will take further research and investigation. Science is a patient endeavor even if us humans are not. There is no need to go metaphysical when we haven't even touched the surface of what can be known physically. 12Twelth, Steve Taylor mistakenly criticizes my approach as scientism when he writes, “The point here is that the metaphysical interpretation of my mother's predicament is completely distinct to science as an enterprise. Lane continually and misguidedly uses science as a justification for scientism. His faith in materialism is literally a faith—a quasi-religious attachment to a particular metaphysical framework. As John Eccles noted, promissory materialism is an irrational superstition, “simply a religious belief held by dogmatic materialists . . . who often confuse their religion with their science.” Nowhere have I advocated scientism. Championing a physics-first approach (along the lines of Edward O. Wilson's Consilience ) doesn't mean that only physical things exist or that I have blind faith in materialism. Rather, it is a practical methodology whereby one attempts to explain any given phenomena by what is known physically about it. By concentrating on that first and exhausting its varied permutations, we will forego the danger of prematurely mistaking a physical event for a spiritual one. Just as when I go to the dentist when I have pain in my wisdom tooth, he looks at my mouth and not my soul. This doesn't discount spirit as such (as if looking merely at root canals can somehow discount metaphysical possibilities), but highlights once again the simplicity of my whole thesis: it's a matter of focus. This isn't scientism and it isn't anti spirituality. It is called being practical. I realize that for many it comes as a surprise when they learn that I have been a lifelong shabd yoga meditator, been to India on numerous research projects studying yogis and mystics, and have a great fondness for Advaita Vedanta philosophy. I love the interior quest and I, along with Sam Harris and others, believe it is vitally important. But let's not confuse domains in our rush to proselytize for the superluminal. As I wrote to JK earlier today responding to my article Understanding Matter, “I sense that too often we rush away from physicalist explanations when we think something is 'rogue' or 'paranormal' but if given more time (and more patient inquiry) we discover (perhaps to our chagrin) that there was indeed a rational, even mundane, reason behind such a weird phenomenon. This prioritizing should not be construed as pre-emption but as a positive aspect of 'skepsis' or a more thorough investigation. In the past when we didn't understand the physics or chemistry of an event, we tended to 'inflate' towards metaphysical or spiritual causations. Now, of course, we are free to do so even now, but I suspect if we do such we run the very real risk of prematurely buying into something as trans-rational when in fact it is anything but. Yet, this scientific centering doesn't have to preclude other approaches as well. Just that we will gather more (not less) evidence for something genuinely supernatural by exhausting the physicalist explanations first.” And, in contrast with what Steve Taylor may suspect, I wrote the following to Greg Stogsdill, “I like your idea that the two inquiries [spiritual and physical] don't have to be mutually exclusive. As a lifelong meditator and an avid reader of Ramana Maharshi and other Indian Advaita Vedanta philosophers, I do understand and appreciate the Consciousness first idea. I just worry that we can confuse domains and end up in a New Age la la land. However, there are those scientists who are attempting to make the Consciousness first idea verifiable and open to falsification, particularly with a mathematical bent.” Finally, I find it a bit bewildering that Steve Taylor would favor a spirit-matter dualism when he writes, “In physicalist terms, we would presume simply that damage to my mother's brain has affected her mental functioning, in the same way that damage to a computer affects it functioning. But from panspiritist terms, we could say that, because of her neurological damage, the brain's role as a transmitter of consciousness has been affected, in the same way that damage to radio stops it transmitting. You might even say that because of the damage to her brain, it is no longer able to act as a 'canaliser' of consciousness, so that she is no longer conscious, but simply a collection of old mental habits and behavioural traits.” There are so many unanswered questions when positing the consciousness as transmitter and brain as receiver hypothesis, not the least of which is why material complexity is necessary for channeling self-reflective awareness. In addition, this the transmitter/receiver idea doesn't solve the knotty question of where consciousness comes from since we now have the added conundrum of trying to figure out exactly where the conscious frequencies are being broadcast. In the ether? From an astral plane? From Bill and Ted's makeshift garage? Moreover, why is the subjective experience of awareness so dramatically altered by the hardware of the brain and by the biochemistry that enlivens it. Why is messing with the objective hardware so damaging to the personal sense of awareness, particularly if they are two distinct entities? I don't see why viewing the brain as a “canaliser” of consciousness is helpful in any progressive way to a scientific study of the subject at hand. Indeed, by postulating such an obvious dualism we seem to have back tracked centuries and have resurrected Rene Descartes' bipolar philosophy. Perhaps we can get rid of this obfuscating bifurcation by seeing the complexity of matter (in whatever form) as a necessary prelude to the manifestation of awareness. This form of monism doesn't see matter and awareness as separate but as two sides of the same physically complex coin. As Koch himself illuminates [Scientific American, June 1, 2018),[3]

“GNW argues that consciousness arises from a particular type of information processing—familiar from the early days of artificial intelligence, when specialized programs would access a small, shared repository of information. Whatever data were written onto this “blackboard” became available to a host of subsidiary processes: working memory, language, the planning module, and so on. According to GNW, consciousness emerges when incoming sensory information, inscribed onto such a blackboard, is broadcast globally to multiple cognitive systems—which process these data to speak, store or call up a memory or execute an action. Now I would like to end my 150th article for Integral World on a note of reconciliation. As much I disagree with Steve Taylor and others of his ilk, I want to encourage them in their efforts for challenging the status quo since critical voices are needed from a variety of fields. Even when we are at loggerheads, our very differences can better illuminate what is needed for a more “integrated” understanding of self-awareness. Personally speaking, I greatly appreciate those who have opinions different than my own because they make me think anew about subjects close to my mind and heart. I tip my hat to Frank Visser for providing all of us with an invaluable forum to share our thoughts uncensored and without rancor. I have learned much from my colleagues who have taken the time to share their insights with me. I feel fortunate to have been able to add my two cents in this ongoing intellectual exchange, even if what I proffer is met with skepticism. Such is the learning process. Notes[1] Christof Koch, Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist, MIT Press, 2012. [2] Steve Paulson, "The Spiritual, Reductionist Consciousness of Christof Koch, What the neuroscientist is discovering is both humbling and frightening him", Nautilus, 47, April 6, 2017. [3] Christof Koch, "What Is Consciousness? Scientists are beginning to unravel a mystery that has long vexed philosophers", www.scientificamerican.com, June 1, 2018

Richard Feynman: “The science knowledge only adds to the excitement, the mystery and the awe of a flower. It only adds, I don't understand how it subtracts.”

Comment Form is loading comments...

|