TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY FRANK VISSER

The Joy of Being Called

‘Extremely Conventional’

Responding to a Wilberian Put-Down

Frank Visser

By overlooking the energetic source of all these dynamic processes, Wilber resorts to an essentially spiritual explanation.

Ken Wilber's recent video "How to Think Integrally"[1] dealt briefly with the criticism he has received for his rather unconventional view of evolution. In my previous essay "Why We Need a Secular Integral" I commented briefly on this fragment—after a brief recapitulation I will add some more interesting details:

“In an attempt to further bolster his view of a 'creative force in evolution', Wilber refers to my critiques over the years of his view of evolution—which was about time.

“Disregarding all of the arguments I have made, he implies to his interviewer De Vos—who just nods brainlessly—that I am a bit behind the times, and represent an 'extremely conventional' view. Authors such as Kauffman, Prigogine, and others, he claims, have written about the drive to self-organization in nature. And that, with emphasis and exasperation, apparently seals the case for Eros.

“extremely conventional…”

“extremely conventional…”

“‘I am always getting criticized by extremely conventional evolutionary theorists, like Frank Visser, because I postulate Eros, an inherent novelty in the cosmos... which by the way is Whiteheads point, the 'creative advance into novelty'. Eros...

Stuart Kauffman, self-organizatoin is built into the universe. Eros...

Ilya Prigogine, a Nobel prize winner. 'Order out of chaos'. Even insentient matter, when pushed far from equilibrium, jumps into higher levels of order. Eros...’ (54:00)

“These complexity scientists, however, do not have a spiritual view of evolution, and would never support Wilber's pet theories. They prefer to scientifically investigate the conditions for complexity to emerge. Energy flows turn out to be of prime importance. No energy flows, no complexity.

“What Wilber doesn't seem to have noticed, is that complexity science is a plea to physicalize biology, not to spiritualize it, as he seems to be doing. The upshot of all this is that natural selection is not the only source of order in nature; self-organization can take a part of that heavy load as well. Where Kauffman thinks order more or less 'crystallizes' just like that, given the right conditions, thus providing 'order for free', Prigogine believes we can get from chaos to order given the right conditions (of being 'far from equilibrium').”

‘ORDER OUT OF CHAOS’ REVISITED

The term "Order out of Chaos" refers to the popular book Nobel Prize winner Ilya Prigogine wrote together with Isabelle Stengers, a French-Belgian philosopher of science.[2] Prigogine received his Nobel Prize in 1977 "for his contributions to non-equilibrium thermodynamics, particularly the theory of dissipative structures." This requires some explanation. Thermodynamics studies the effect of heat on matter. Matter itself tends to be rather inert and passive. But by applying heat to matter, interesting things can result. This insight opened up a new field of physics, that bordered on the sciences of life. Living organisms by definition are exchanging energy and matter with their environments. Without these exchanges they would soon perish—or be in a state of "equilibrium", the equivalent of death. By constantly taking in food organisms are able to remain in a state of "non-equilibrium", in which complexity can be built up and sustained. Systems that constantly exchange energy with their environment Prigogine called "dissipative structures". Energy dissipates in this process, because wasteful energy in the form of heat is generated. But this process allows them to "self-organize" and thrive.

This energy connection to the environment is crucial for understanding what makes biological complexity possible, especially because Wilber's spiritual ideas about what animates nature and evolution differs dramatically from what these scientists are telling us. So this offers us a nice opportunity to contrast "thinking integrally" with the more mundane "thinking conventionally"—extremely or not—as practiced in science. It might turn out that what makes evolution tick is not so much a spiritual drive as well as a continuous flow of energy from the environment.

Says Wikipedia in the article on "Biological thermodynamics":

Non-equilibrium thermodynamics has been applied for explaining how biological organisms can develop from disorder. Ilya Prigogine developed methods for the thermodynamic treatment of such systems. He called these systems dissipative systems, because they are formed and maintained by the dissipative processes that exchange energy between the system and its environment, and because they disappear if that exchange ceases. It may be said that they live in symbiosis with their environment.

Living organisms are often mistakenly believed to defy the Second Law because they are able to increase their level of organization. To correct this misinterpretation, one must refer simply to the definition of systems and boundaries. A living organism is an open system, able to exchange both matter and energy with its environment.

This is good to bear in mind, given the fact that Wilber frequently contrasts this Second Lay of Thermodynamics, according to which disorder will unavoidably increase, with the observed increase in complexity we see in nature. A rather embarrassing sign of ignorance about how nature works! Wikipedia continues:

For example, a human being takes in food, breaks it down into its components, and then uses those to build up cells, tissues, ligaments, etc. This process increases order in the body, and thus decreases entropy. However, humans also 1) conduct heat to clothing and other objects they are in contact with, 2) generate convection due to differences in body temperature and the environment, 3) radiate heat into space, 4) consume energy-containing substances (i.e., food), and 5) eliminate waste (e.g., carbon dioxide, water, and other components of breath, urine, feces, sweat, etc.). When taking all these processes into account, the total entropy of the greater system (i.e., the human and her/his environment) increases. When the human ceases to live, none of these processes (1-5) take place, and any interruption in the processes (esp. 4 or 5) will quickly lead to morbidity and/or mortality.

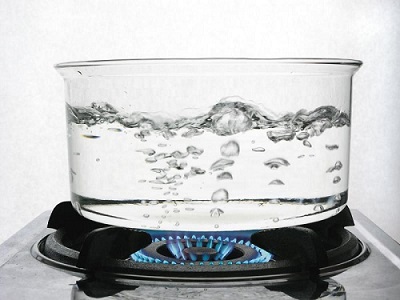

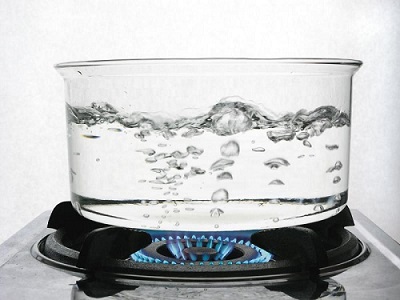

The understand all the factors involved, a more simple example is illustrative. Let's take the boiling of water, after being heated for some time.

Water reaches boiling point by a continuous influx of heat.

When cold water is stored in a pan, it just rests in a stable state of equilibrium. But when heat is applied, things change. At first, nothing visibly happens to the water, which slowly rises in temperature. The water at the bottom of the pan gets warmer and warmer, and this heat is transferred upwards, very slowly. Small bubbles can be seen to rise upwards to the water, only to evaporate in the air above it.

But when "boiling point" is reached, a massive change occurs. The water shows erratic streams with larger bubbles, technically called "convection". The change is miraculous: how do the uncountable water molecules "know" they have to form in a certain arrangement? And why are they doing this in the first place? It turns out that because of this macroscopic transformation, the water mass can get rid of the heat much faster then would be possible through simple conduction alone.

So we have the following elements:

- cold water is in a state of equilibrium

- a fire below it is turned on

- a new state of non-equilibrium is created

- heat gets conducted slowly upwards through the water

- a gradient is set up between cold and warm water

- gradually small bubbles rise up though the water

- at boiling point the water mass changes its form spectacularly

- these transformations allow heat to be dispersed more quickly

- these form patters are very unlikely to happen by itself

- it takes continuous energy to create and sustain these transformations

- boiling is a non-equilibrium "steady state" "out of equilibrium"

- in this state, the net result is the production of heat

- this whole process is purposeful: heat dispersal

- when the fire is turned off, boiling stops immediately

- in a nutshell this is what happens with biological life

Most of these details are missed by Wilber's superficial glance at the work of Ilya Prigogine and what non-equilibrium thermodynamics means for our conception of life. Instead, he co-opts these notions to bolster his spiritual views.

An uninformed observer could wonder, why water would suddenly change its shape and show different behavior. Is water capable, "by its own power", to jump to this higher form of complexity? Is there perhaps a latent power in water, or in matter as such, that accomplishes this miraculous feat? Here we have Wilber's view of nature.

The closing of the gap between the physiosphere and the biosphere came precisely in the rather recent discovery of those subtler and originally hidden aspects of the material realm that, under certain circumstances, propel themselves into states of higher order, higher complexity, and higher organization. In other words, under certain circumstances matter will "wind itself up" into states of higher order, as when the water running down a drain suddenly ceases to be chaotic and forms a perfect funnel or whirlpool. Whenever material processes become very chaotic and "far from equilibrium," they tend under their own power to escape chaos by transforming it into a higher and more structured order—commonly called "order out of chaos." (Sex, Ecology, Spirituality, p. 13-14)

What is conspicuously absent from this picture is the absolute necessity of energy flows. Without these flows, no non-equilibrium state will be created. No "propelling into higher states of higher order, higher complexity and higher organization" will happen. Matter will not "wind itself up into states of higher order". Material process will not "under their own power escape by transforming [chaos] into a higher and more structured order". But with energy flows, all of this and more will happen.

A much better explanation than the rather mystifying and esoteric "subtler and originally hidden aspects of the material realm" that mysteriously start to come alive.

Wilber often expresses wonderment about the statistical unlikelihood of these higher structural formations. How could they possible have happened by chance alone? (Indeed, they are not the product of chance alone.) Are they not a sure sign that "something other than chance is pushing the universe?"

In other words, something other than chance is pushing the universe. For traditional scientists, chance was their god. Chance would explain it all. Chance—plus unending time—would produce the universe. But they don't have unending time, and so their god fails them miserably. That god is dead. Chance is not what explains the universe; in fact, chance is what that universe is laboring mightily to overcome. Chance is exactly what the self-transcending drive of the Kosmos overcomes.

-- Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution, 1996, p. 26

By overlooking the energetic source of all these dynamic processes, Wilber resorts to an essentially spiritual explanation—without being able to specify how such a spiritual force or energy, which he usually refers to as "Eros", can possible make these things happen. What is more, he is incapable of seeing the purpose behind these transformations. Instead of seeing the growth of biological complexity as something which contradicts or goes against the Second Law of Thermodynamics. it is possible—though this is a rather unconventional view—to see it as working in line with this larger goal. Complex systems such as living organisms turn out to be capable of converting high-quality energy into low-quality heat, and by "degrading this gradient" accomplish all their magnificant feats of biological ingenuity.

Many authors taking a big picture view of nature have come to similar conclusions. David Christian argued eloquently for a view of biological and cultural complexity, in which an "energy tax" had to be paid to the supreme Law of Entropy.[3] Daniel Dennett described the process as "It is not impossible to oppose the trend of the Second Law, but is is costly."[4] Dorion Sagan and Eric Schneider state this basic law of nature, at the end of a book-lenth treatment of this topic, as:

Life and other complex systems not only do not contradict the second law but exist because of it. Moreover, life and other complex systems reduce preexisting gradients more effectively than would be the case without them.[5]

THE CONVENTIONS OF GOOD SCIENCE

If "thinking integrally" means claiming scientific support for one's own spiritual views, from Nobel Prize winners who did not share your views, then I prefer not to belong to that category at all. If it means avoiding any opportunity to discuss one's views with informed critics, then this is not much of an ideal to aspire to. If it means that these critics can be put down as "extremely conventional", thus contrasting them to one's own post-conventional (or post-postconventional, or post-post-postconventional, or, whatever) views, then the integral project is in grave danger of becoming an insulated ideology, which tries to survive by endlessly repeating its own unsubstantiated claims to fame. By presenting itself is "a view from 30.000 feet" it apparently doesn't feel the obligation to have the details right. Details that are not minor. If authority arguments are seen as more important than careful reasoning; if authoritarian response to questioning is the norm…

But if being "extremely conventional" means to take science seriously, to have an informed knowledge of a certain field, and to carefully state what certain scientists did or did not claim or discover, if it means that every knowledge claim can and should be challenged—then by all means, let us be "extremely conventional"! In that case, I prefer to be in the company of another Nobel Prize winner, physicist Richard Feyman, whose posthumously published collection of essays was called "the pleasure of finding things out", conveying the spirit of his approach to scientific knowledge.

These are simply the conventions of good science. But apparently not of "integral thinking".

Even if it concerns such simple things as boiling water, the insight they can convey to us about the larger workings of nature are immense. Next time you make a cup of tea for yourself, think of this.

NOTES

[1] Ken Wilber and Corey de Vos, "How to Think Integrally", www.integrallife.com, September 19, 2018.

[2] Ilya Prigogine & Isabelle Stengers, Order Out Of Chaos: A New Dialogue with Nature, Flamingo, 1984.

[3] David Christian, Origin Story: A Big History of Everything, Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

[4] Daniel Dennett, Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life, Simon & Schuster, 1995.

[5] Eric Schneider & Dorion Sagan, Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics and Life, The Univ. of Chicago Press, 2005.

|

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).