TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY FRANK VISSER

‘Precisely nothing

new or unusual’

Ken Wilber on Darwin's Lasting Contribution

Frank Visser

If you put your faith more in Schelling and Hegel, rather than Darwin and Mendel, you have a scientific credibility problem.

It is always fun and instructive to look up Ken Wilber's stray comments about Charles Darwin, in which he tries to situate his own "theory" of evolution vis-a-vis the scientific understanding of evolution. In Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995), his most academic work to date, we find a couple of these statements. To put these in context: Wilber's view of evolution is inspired by the German Idealists (Schelling, Hegel) and their descendants (Bergson, Whitehead). It is not restricted to the biosphere but is cosmic in nature. Compared to this grand vision, Darwin's contribution is pictured as merely providing "evidence for a conception that was in the main already known in advance." Wilber emphasizes that the notion of evolution was already known long before Darwin. Charles Darwin should be seen as having simply supplied "empirical evidence for a scheme already known and accepted", namely: evolution is driven by Spirit or Eros.

It will not surprise you that this unorthodox and even excentric reading of Darwin's contribution is completely at variance with the current Darwin scholarship (which is so massive that it has been called a veritable "Darwin industry"). Having read quite some primary (Darwin's main works On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man) and secondary (popular works on evolution by Dawkins, Coyne, Zimmer et.al) evolutionary science literature in the past decade, I have recently turned to such wide-ranging tertiary literature as Evolution: The History of An Idea (1983/2009) by Peter Bowler and Darwin and Its Discontents (2008) by Michael Ruse. Both authors are evolutionary historians who have written dozens of books on the topic of Darwin interpretation and evaluation.

These volumes take many ideological and scientific viewpoints into account, both pro and contra Darwin and his theory of natural selection. They also separate the science from the socio-cultural or religious ideology around it. We will need to do this in the case of Ken Wilber as well.

For example, the early French evolutionary literature that pre-dated Darwin was linked to a revolutionary spirit due to the political turmoil of those days, so it was opposed to gradualism. In Germany Idealist philosophers before Darwin imagined a divine Spirit being active behind both history and evolution in culture and nature. In England, the growing middle-class picked up the idea of progress from Darwin's theory, hoping for a better future. Some social theorists post-Darwin saw Darwin's theory as the legitimization of a harsh attitude towards the not-haves, since it taught us the "survival of the fittest" (the expression is Spencer's, not Darwin's). And as we will see in the case of Wilber, some see in evolution primarily a spiritual phenomenon of increasing complexity and consciousness, culminating in us humans.

None of these groups have come to terms with the radicality of Darwin: that species can emerge without divine intervention, in gradual (and sometimes not so gradual) steps, without any guidance, plan or purpose.

In Sex, Ecology, Spirituality Wilber also construes a major problem between the notion of evolution or progress and the science of thermodynamics, which predicts an increase of entropy or disorder, not order, in the cosmos at large. The implication being that if the Second Law of Thermodynamics holds true, no real evolution or continuous increase of order would be possible. As a solution to this cosmic problem he points to the sciences of complexity, which in his understanding have discovered and substantiated a drive even within matter itself towards complexity. This, according to Wilber, heals the split between the physiosphere and the biosphere, which had grown during the rise of science and its discoveries, for both were now oriented towards higher complexity.

Here, too, we should carefully separate the science and the ideological use that is made of it by Ken Wilber. It turns out there is no such contradiction as suggested by Wilber. Instead there is merely a paradox between the Second Law (or entropy) and evolution, in the sense that evolution is possible, even given the Second Law, since it draws precisely on the energy that is made available through stars such as our Sun (I have argued this point in several essays on Integral World so won't repeat this here).

Instead of merely collecting evidence for a view that was already known, Darwin radically broke with that view. It is here that Wilber's scholarship is most wanting and in need of a substantial correction.

THE ORIGINALITY OF DARWIN

With this background in mind, we will annotate the passages in Sex, Ecology, Spirituality where Wilber explicitly refers to Charles Darwin and his main significance:

Against this early (and partial) scientific [deterministic] understanding of the physiosphere, which was now seen as a reversible mechanism irreversibly running down, came the work of Alfred Wallace and Charles Darwin on evolution through natural selection in the biosphere. Although the notion of evolution, or irreversible development through time, had an old and honorable history (from the Ionian philosphers to Heraclitus to Aristotle to Schelling), it was of course Wallace and Darwin who set it in a scientific framework backed by meticulous empirical observations, and it was Darwin especially who lit the world's imagination with his ideas on the evolutionary nature of the various species, including humans. (p. 10)

No problem here. Wilber sketches the contrast of a universe that is winding down as described by physics, and evolution which seems to be a kind of winding up. Also, he notes that evolution itself was no new idea, but it was "set in a scientific framework" by Darwin and Wallace.

What isn't mentioned is how Darwinian evolution differs in its mechanism from all of its predecessors. Where these older "theories" of evolution were primarily "transformationist", Darwin's theory was explicitly "variationist" (the terms are from evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr). This means that, instead of looking for some unknown and unexplained interior drive within organisms, the cause of evolution was now seen as a combined process of variation and selection. Where variation is largely random, selection made this process non-random, and hence complexity can arise, and even be fine-tuned to the demands of the environment. This is Evolution 101.

Wilber continues:

Apart from the specifics of natural selection itself (which most theorists now agree can account for microchanges in evolution but not macrochanges), there were two things that jumped out in the Darwinian worldview, one of which was not novel at all, and one of which was very novel. The first was the continuity of life; the second, speciation by natural selection. (p. 10)

Here Wilber correctly notes that natural selection was Darwin's unique contribution, but rather casually he restricts its scope to "microchanges", and adds that "most theorists now agree" with this assessment. This is a rather irresponsible claim. It is, in fact, a claim often made by creationists. What is worse, Wilber doesn't mention any of these theorists. Nor does he define what he sees as a "macrochange".

Is natural selection incapable of so-called "macrochanges"? Let's assume the human eye or the bird's wing is such a macrochange, a complex organ consisting of many parts that need to be adjusted carefully to be fully functional. In A Brief History of Everything (1996) Wilber tried to argue precisely this point, against neo-Darwinism and in favor of a view of evolution as "Spirit-in-action", but in later communications he has retracted this. Should we think more of different species or even genera or orders, like whales? The evolution of whales from tetrapods is meticulously documented. Perhaps whole phylae such as the chordata (of which the vertebrae are a subphylum?)

This is quite crucial, but skipped over by Wilber because he needs to prove his point that macrochanges are Spirit-driven (how and when, he will not be able to tell you, but usually he says its just a matter of "self-organization". But since when does self-organization create elephants? That remains the province of natural selection).

And there's another glaring omission in Wilber's reading of Darwin's originality, the common descent of all forms of life from a common ancestor:

"Universal common descent through an evolutionary process was first proposed by the British naturalist Charles Darwin in the concluding sentence of his 1859 book On the Origin of Species." (Wikipedia)

Wilber continues:

The idea of the continuity of life—the web of life, the tree of life, the "no gaps in nature" view—was at least as old as Plato and Aristotle, and, as I briefly mentioned, it formed an essential ingredient in the notion of the Great Chain of Being. Spirit manifests itself in the world in such a complete and full fashion that it leaves no gaps in nature, no missing links in the Great Chain. And, as Lovejoy noted, it was the philosophical belief that there are no gaps in creation that directly led to the scientific attempts to find not only the missing links in nature (which is where that phrase originated) but also evidence of life on other planets. All of these "gaps" needed to be filled in, in order to round out the Great Chain, and there was precisely nothing new or unusual in Darwin's presentation of the continuous tree of life. (p. 10-11)

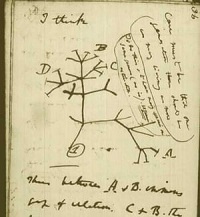

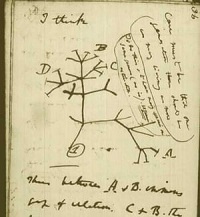

A page from Darwin's Notebook B

A page from Darwin's Notebook B

showing his sketch of the tree of life.

Well, not quite. The metaphor of a chain is lineair or one-dimensional, whereas a tree is three-dimensional. What is more, where older evolutionists pictured the Great Chain of Being, as a fixed sequence of species (Bonnett), the first Trees of Life were equally linear (Haeckel), pictured as an upright tree with a huge trunk, and minor branches. But Darwin's Tree of Life was again much less one-dimensional—more like a bush or shrub. And where the chain slots in the Great Chain were seen as created by God, the organisms that evolved were new creatures, unplanned and unforeseen. And where the old conviction was that nature didn't leave any gap unfilled with life due to Divine Abundance, in the scientific view this continuity was due simply to the fact that generations of organism are connected in one long sequence. Wilber highlights the continuity in the Tree of Life, but overlooks the fact that something else is going on here: an exuberant diversification of life in all directions.

As to the term "missing link", it is an unscientific term in our modern understanding of evolution:

The missing link is an unscientific term for transitional fossils. It is often used in popular science and in the media for any new transitional form. The term originated to describe the hypothetical intermediate form in the evolutionary series of anthropoid ancestors to anatomically modern humans (hominization). The term was influenced by the pre-Darwinian evolutionary theory of the Great Chain of Being and the notion (orthogenesis) that simple organisms are more primitive than complex organisms.

The term "missing link" has fallen out of favor with biologists because it implies the evolutionary process is a linear phenomenon and that forms originate consecutively in a chain. Instead, last common ancestor is preferred since this does not have the connotation of linear evolution, as evolution is a branching process. (Wikipedia)

But let's move on.

Leibnitz had taken profound steps to "temporalize" the Great Chain, and with Hegel and Schelling we see the full-blown conception of a process or develomental philosophy applied to literally all aspects and all spheres of existence.

But it was Darwin's meticulous descriptions of natural species and his unusual clarity of presentation, combined with his hypothesis of natural selection, that propelled the concept of development or evolution to the scientific forefront. (p. 11)

Please note that development and evolution are by no means synonyms. For Wilber they are.

Again, Wilber extolls the idealist view of evolution here as something that is "applied to literally all aspects and all spheres of existence". He sees no incompatibility yet between both views (more on that later), and credits Darwin with making the notion of evolution more well known within science (compared to philosophy).

[12]b. Increasing differentiation/integration. This principle was given its first modern statement by Herbert Spencer (in First Principles, 1862): evolution is "a change from an indefinite, incoherent homegeneity, to a definite, coherent heterogeneity, through continuous differentations and integrations" (this definition of the term evolution allowed biologists to begin using it instead of Darwin's phrase "descent with modification"). (p. 68)

This quote comes from the Twenty Tenets, which Wilber describes as the “'laws' or 'patterns' or 'tendencies' or 'habits'” that “all known holons seem to have in common.” (p. 34). But these are rather abstract descriptions, not evolutionary causes.

As one example, Tenet 2 reads "holons emerge", but that tells us "precisely nothing" (to use Wilber's favorite expression) about how this process happens or is caused. One might say: that's exactly the meaning of "emergence", but that's too glib. The emergence of a water molecule H2O through the combination of one Oxygen and two Hydrogen atoms is well understood, and the characteristics of water as a fluid can be understood based on its chemical composition. Evolutionary novelty can also be conceptualized as emergence, but this tends to mystify it. Evolutionary biologists are deeply studying how new organs or species can evolve or emerge, often by re-using existing structures. The human ear, for example, has evolved from the jaw bones of reptiles. Now Wilber needs these processes to remain mysterious, so he can introduce his Spirit-in-action, and you will never learn from him how science makes progress in these areas.

It is true that Darwin didn't use the term "evolution" much. In fact, only once in his Origin of Species and then literally only as the last word!

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

In later editions he added "breathed by the Creator", a fact which he regretted a few years later, when he wrote: "I have long regretted that I truckled to public opinion & used Pentateuchal term of creation, by which I really meant 'appeared' by some wholly unknown process. It is mere rubbish thinking, at present, of origin of life; one might as well think of origin of matter."

What is more telling is that Wilber refers to Herbert Spencer, a contemporary of Darwin who had his own ideas about the mechanism of evolution, and published them around the same time as Origin. They are very similar to Wilber's ideas:

Spencer's attempt to explain the evolution of complexity was radically different from that to be found in Darwin's Origin of Species which was published two years later. Spencer is often, quite erroneously, believed to have merely appropriated and generalised Darwin's work on natural selection. But although after reading Darwin's work he coined the phrase 'survival of the fittest' as his own term for Darwin's concept,[5] and is often misrepresented as a thinker who merely applied the Darwinian theory to society, he only grudgingly incorporated natural selection into his preexisting overall system. The primary mechanism of species transformation that he recognised was Lamarckian use-inheritance which posited that organs are developed or are diminished by use or disuse and that the resulting changes may be transmitted to future generations. (Wikipedia)

DARWINISM AS OBSCURANTISM

Towards the end of Sex, Ecology, Spirituality Wilber takes up the subject of Darwin's contribution again. He recaptures:

Thus, a century before Darwin, theories of cosmic and human evolution were springing up everywhere, theories that, as we saw, were looking for "missing links," but missing links that were now believed to have unfolded in time and history. Leibnitz maintained that "the species of animals have many times been transformed... The entire universe, he suggested, may have been one that developed, because we see everywhere the creative advance of nature—what he called "transcreation" (transformation)." (p. 480)

This is essentially the pre-Darwinian understanding of evolution, which Wilber never seems to have outgrown.

And here we have our old friend Eros, ever striving for great unions, greater integrations, the binding love that unfolds more, enfolds more (Eros/Agape), the omega force hidden even in matter, driving it into higher levels of self-organization and self-transcendence, the omega force that will not let even matter sit around in unorganized heaps. We will return, in a moment, to this part of the story, and to Darwin's drudging and dutiful accumulation of evidence for a conception that was in the main already known in advance. (p. 481-482)

As you can see, Wilber is harping on the theme of a generic but unspecified drive behind evolution, a notion science rejects categorically.

But the immediate effect of this "developmental philosophy" [of Schelling] (or the philosophy of Eros) was that the notion of evolution was everywhere "in the air"—and this was still six decades before Darwin. "A theory of emergent evolution [was] demanded by Schelling's view of the world as a self-developing organic unity. Indeed, he explicitly refers to the possibility of evolution. He observes, for instance, that even if man's experience does not reveal any case of the transformation of one species into another, lack of empirical evidence does not prove such a transformation is impossible. For it may well be that such changes can take place only in a much longer period of time than that covered by man's experience." (p. 491)

When Darwin came along and dutifullly supplied some of the empirical evidence for biological evolution, it shocked nobody except the remnants of the mythic believers in the literal Genesis myth; but they were already shocked by what Schelling and other developmentalists were doing anyway. (p. 492)

Here Wilber makes a big mistake: to see Darwin as just providing evidence for a "conception that in the main was already known in advance." He fails to see Darwin's originality. As evolutionary historian Peter Bowler wrote in Science:

The publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species in 1859 is widely supposed to have initiated a "revolution" both in science and in Western culture. Yet there have been frequent claims that Darwinism was somewhow "in the air" at the time, merely waiting for someone to put a few readily available points together in the right way. The fact that Alfred Russell Wallace independently formulated a theory of natural selection in 1858 is taken as evidence for this position. But Darwin had created the outlines of the theory 20 years earlier, and there were significant differences between the way in which he and Wallace formulated their ideas. In this essay I argue that Darwin was truly original in his thinking, and I support this by addressing the related issue of defining just why the theory was so disturbing to his contemporaries.[1]

In this article, Bowler doesn't mention German idealists as forerunners of Darwin (let alone Darwin as their dutiful servant), but sketches a detailed picture of the available notions about evolution around the time Darwin wrote. Darwin's conception of evolution did away with any pre-ordained goal of evolution or even the fixed nature of species. Created species were replaced by common ancestors in the Darwinian model. By studying artificial selection Darwin got convinced about the role and effectiveness of natural selection over long spans of time. He thought that the pressure of competition was necessary to make this effective. (Spencer, who coined the term "survival of the fittest", believed more in self-improvement).

Says Jonathan Howard in his Darwin: A Very Short Introduction:

The profound distinction that Darwin rightly perceived between his own evolutionism and that of his many predecessors lay in his solution to the crucial but subsidiary question of the mechanism of evolutionary change. (p. 24)

And yes, Darwin's theory was "disturbing"—notwithstanding Wilber's "it shocked nobody". Instead of merely collecting evidence for a view that was already known, Darwin radically broke with that view. It is here that Wilber's scholarship is most wanting and in need of a substantial correction.

The lasting contribution of Darwin's theory, then, was not that it discovered a mechanism for macroevolution, for it did not; rather, it obscured for over a century the fact that a genuine theory of evolution demands something resembling Eros. Darwin's lasting contribution was primarily a massive obscuratanism [sic]. Scientists all cheery and self-content began to scrub the universe clean of anything resembling love and its all-encomplassing embrace, and all congratulated themselves on yet another victory for truth (Wallace, as is well known, did not think natural selection could replace Eros; evolution was itself, he thought "the mode and manner of Spirit's creation," and Darwin himself notoriously wavered). (p. 492-493)

Wilber portrays Darwin in the end as an obscurantist (mark the strange typo: obscuratanism—Darwin as Satan?). His tone becomes condescending towards science and he loses all sense of proportion. As said before, scientists are well able to explain macrochanges—especially when evo devo, epigenetics and the like are included. And in contrast to Wilber, they are explicit in their theories about how evolutionary transformation are effected in a step-wise manner. Wilber can't stand their successes, and sees them as self-congratulary without any deserved reason. But even worse, he brings up Wallace as the one who at least saw the light: "as is well known [he] did not think natural selection could replace Eros." Well, in 1889, Wallace wrote the book Darwinism, which explained and defended natural selection—except for human beings.

To top if off, "the mode and manner of Spirit's creation" is obviously Wilberian phraseology and in no way a quote from Wallace.

The problem Wallace had with Darwin was about sexual selection. And in his later life, he became a spiritualist, believing that the mind of human beings was created by the Divine.

Shortly afterwards, Wallace became a spiritualist. At about the same time, he began to maintain that natural selection cannot account for mathematical, artistic, or musical genius, as well as metaphysical musings, and wit and humour. He eventually said that something in "the unseen universe of Spirit" had interceded at least three times in history. The first was the creation of life from inorganic matter. The second was the introduction of consciousness in the higher animals. And the third was the generation of the higher mental faculties in humankind. He also believed that the raison d'être of the universe was the development of the human spirit. These views greatly disturbed Darwin, who argued that spiritual appeals were not necessary and that sexual selection could easily explain apparently non-adaptive mental phenomena. (Wikipedia)

Again, Wilber gives the "sanitized" version of Darwinism, in which Darwin can be seen as "simply supplying empirical evidence for a scheme already known and accepted, namely, evolution as God-in-the-making".

Darwin's "naturalism"—this denatured nature—seemed, to the dominant flatland worldview, to cover all the necessary bases. Mononature alone was all the "spirit" men and women needed, and all the "spirit" there was.

But it wasn't the Darwinian "revolution" that would play most decisively into the hands of the Descenders. After all, the Darwinists could always be seen, whether they wished to or not, as simply supplying empirical evidence for a scheme already known and accepted, namely, evolution as God-in-the-making, Eros not simply seeking Spirit but expressing Spirit all along via a series of every-higher ascents, which Darwin had merely chronicled in a not-very-surprising fashion. (p. 510)

This is "simply" (to echo Wilber) a ridiculous and unfounded conclusion, at variance with everything we know about Darwin and his times. But it is the speculative, "Spencerian", idealist philosophy Wilber believes in and which filters all his reading of science.

To call Darwin's solution to the problem of speciation "not-very-surprising" is to grotesquely misread his importance for science.

Then Wilber turns to the subject of thermodynamics, and the danger it posed to any spiritual view of the universe, and even to any evolutionary view, spiritual or otherwise conceived.

Darwin was never the problem. It was Carnot , Clausius, and Kelvin. And about the time that Darwin was on HMS Beagle, William Kelvin and Rudolf Clausius were formulating two versions of the second law of thermodynamics, versions later shown to be equivalent, and both of which were taken to mean: the universe is running down. In all real physical processes, disorder increases.…

The laws of thermodynamics seemed to totally undermine any sort of "organic unity" or "self-organizing nature" or "the total and unitary process of self-manifestation" (Schelling, Hegel)—let alone any sort of Eros operative "even in the lowest state of matter" (Kant). And if the Idealists couldn't even get the first floor of evolution right, why should we believe them about any "higher stages"? There is no Eros in the physical world, and if the physical world is part and parcel of Spirit's manifestation, then there is and can be no Eros in Spirit. Which is to say, there is no Spirit, period.

This completely undercut any sort of idealist or spiritual view of evolution or manifestation in general. The first floor of the magnificent Idealist edifice crumbled, and the higher floors almost immediately followed suit (Idealism would survive in any viable form no more than a few decades after Hegel's death). (p. 511)

For sure, the question "if the Idealists couldn't even get the first floor of evolution right, why should we believe them about any 'higher stages'?" is pertinent as to the viability of Wilber's own metaphysics. What Wilber fails to see, is that the Second Law and evolution are not mutually exclusive, as any online reference covering evolution and entropy can tell us. Says Talkorigins.org, discussing major misconceptions frequently held in this field[2]:

"Evolution violates the 2nd law of thermodynamics."

This shows more a misconception about thermodynamics than about evolution. The second law of thermodynamics says, "No process is possible in which the sole result is the transfer of energy from a cooler to a hotter body." [Atkins, 1984, The Second Law, pg. 25] Now you may be scratching your head wondering what this has to do with evolution. The confusion arises when the 2nd law is phrased in another equivalent way, "The entropy of a closed system cannot decrease." Entropy is an indication of unusable energy and often (but not always!) corresponds to intuitive notions of disorder or randomness. Creationists thus misinterpret the 2nd law to say that things invariably progress from order to disorder.

However, they neglect the fact that life is not a closed system. The sun provides more than enough energy to drive things. If a mature tomato plant can have more usable energy than the seed it grew from, why should anyone expect that the next generation of tomatoes can't have more usable energy still? Creationists sometimes try to get around this by claiming that the information carried by living things lets them create order. However, not only is life irrelevant to the 2nd law, but order from disorder is common in nonliving systems, too. Snowflakes, sand dunes, tornadoes, stalactites, graded river beds, and lightning are just a few examples of order coming from disorder in nature; none require an intelligent program to achieve that order. In any nontrivial system with lots of energy flowing through it, you are almost certain to find order arising somewhere in the system. If order from disorder is supposed to violate the 2nd law of thermodynamics, why is it ubiquitous in nature?

The thermodynamics argument against evolution displays a misconception about evolution as well as about thermodynamics, since a clear understanding of how evolution works should reveal major flaws in the argument. Evolution says that organisms reproduce with only small changes between generations (after their own kind, so to speak). For example, animals might have appendages which are longer or shorter, thicker or flatter, lighter or darker than their parents. Occasionally, a change might be on the order of having four or six fingers instead of five. Once the differences appear, the theory of evolution calls for differential reproductive success. For example, maybe the animals with longer appendages survive to have more offspring than short-appendaged ones. All of these processes can be observed today. They obviously don't violate any physical laws.

Charles Darwin has obscured the “Spirit of Evolution”, according to Wilber, but based on complexity science and some Hindu metaphysics he will bring Spirit back. That's basically his message to the world. However, this will never be an evolutionary theory, but is an evolutionary theology.

CONCLUSION

Wilber seems to be confused about the point he wants to make about Charles Darwin. These two things don't go together very well—and both claims are wrong:

- Darwin merely collected evidence for a view that was already in the air.

- Darwin obscured a spiritual view that was already known in advance.

But you can't have it both ways. Either Darwin provided evidence for a conception of evolution, or he obscured such a conception.

What Wilber sees as obscuration, science sees as clarification, even revelation. For this was exactly "Darwin's dangerous idea" (Dennett): Darwin turned the earlier Mind-first view of evolutionary design, this Cosmic Pyramid, on its head and clarified how complexity could evolve without the hand of a divine Creator or Spirit.

God

Mind

Design

O r d e r

C h a o s

N o t h i n g

Darwin was never the problem? Darwin was precisely the problem! Many, even today, are not willing to accept the radicality and originality of his theory, and yearn for "something" that is behind it all. As Dennett explains in his Darwin's Dangerous Idea:

A prominent feature of Pre-Darwinian world-views is an overall top-to-bottom map of things. This is often described as a Ladder; God is at the top, with human beings a rung or two below (depending on whether angels are part of the scheme). At the bottom of the Ladder is Nothingness, or maybe Chaos, or maybe Locke's inert, motionless matter. Alternatively, the scale is a Tower, or, in the intellectual historian Arthur Lovejoy's memorable phrase, a Great Chain of Being composed of many links.…

Give me Order, [Darwin] says, and time, and I will give you Design. Let me start with the regularities of physics—and I will show you a process that eventually will yield products that exhibit not just regularity but purposive design.…

Darwin's inversion suggests that we abandon that presumption and look for sorts of excellence, or worth and purpose, that can emerge, bubbling up out of "mindless, purposeless forces." (p. 65-66)

And it shocked nobody? This "strange inversion of reasoning" as one reviewer of Origin phrased it, brough "vertigo and revulsion" in many of its readers, according to Dennett. He may be a more trustworthy guide when it comes to assessing Darwin's lasting significance, and the emotional impact he had on his contemporaries.

It looks like we don't need a spiritual view of evolution to "beat" the Second Law, nor to assess the real contribution Charles Darwin has made to our understanding of evolution. It is high time that integralists study science by themselves instead of relying solely on Wilber's biased reporting. The example of Darwin makes this abundantly clear. If you put your faith more in Schelling and Hegel, rather than Darwin and Mendel, you have a scientific credibility problem.

Charles Darwin has obscured the “Spirit of Evolution”, according to Wilber, but based on complexity science and some Hindu metaphysics he will bring Spirit back. That's basically his message to the world. However, this will never be an evolutionary theory, but is an evolutionary theology.

NOTES

[1] Peter Bowler, "Darwin's Originality", Science, vol 323, 9 January 2009.

[2] "Thermodynamics, Evolution and Creationism", www.talkorigins.org

|

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).