|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD

Characteristics of Our Emerging WorldviewWestern and Global South Worldviews ComparedJoseph DillardIntroduction

History followed different courses for different peoples because of differences among peoples' environments, not because of biological differences among peoples themselves.

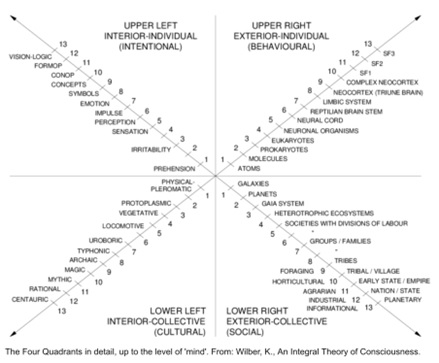

Any assessment of worldviews is made through the subjectivity of our own worldview. To this end, I will share my own: a background in the Western worldview supplemented by years of study of the Indian, Chinese, and Russian worldviews, within the context of the integral worldview. This introduction includes an explanation of those aspects of the integral worldview through which I filter my treatment of these various other worldviews. Those integral aspects are primarily multi-perspectivalism and its holonic, four-quadrant integral model. Holons are wholes that are comprised of parts. All parts exist in contexts; all contexts contain parts. All sets contain subsets; all members of sets and subsets exist in larger sets. Therefore, the concept of holons is one of inseparable interdependence of wholes and their constituent elements. This principle is carried forward, but in greater detail, when we examine the elements that comprise any holon. Holons are comprised of (at least) four quadrants. Just as no whole exists without parts and no parts exist without a contextualizing whole, so no inside exists without an outside and no outside exists without an inside. Similarly, just as in holons themselves, no individual exists outside of a collective and no collective exists without individual elements. These principles create four “facets,” “faces,” or perspectives of every holon, an interior individual (II), an interior collective (IC), an exterior individual (EI), and an exterior collective (EC) perspective. You can see these four in the illustration below. Every individual and social (collective) holon will tend to emphasize one of these four quadrants the most, which means that it is most likely to de-emphasize or be weakest in its opposite. If you are focused on consciousness, the development of your sense of self, and spirituality, your emphasis is on interior and individual domains and interests, or the “upper left” or interior individual (II) quadrant. The implication is that your weakest area will be the opposite, that is, your interest in, understanding of, and empathy with that which is “not-self,” or the “other,” the external collective (EC) quadrant. The domain of the foreign, meaningless, or threatening will be the area you need to focus on most in order to bring your four quadrants into balance. Of course, you may be more or less in balance. Major imbalance, on an individual interior level (II) is called “psychopathology.” In the interior collective level (IC) it is cultural maladjustment; in the exterior individual (EI), deviancy, or failure; and in the exterior collective quadrant (EC), it is immorality and unlawfulness. Therefore, as we move through the priorities of different worldviews, keep in mind the question, “Which quadrant is least incorporated? Which priorities need to be emphasized to bring the worldview into greater balance?” Then, we can ask the same questions about worldviews themselves in order to gain a sense of how they might best complement and supplement one another. Although it is not demonstrated on the illustration below, each quadrant can be subdivided into inner and outer, subjective and objective “zones,” to which Wilber gives the rather unpoetic designation of “integral methodological pluralism.” For example, every worldview, which is primarily a “lower left” or an interior collective (IC) perspective, has an outward facing, “exterior,” objective, non-private face, and an inward facing, “interior” and subjective, private face. We will take a look at the implications of both. Below is Wilber's original version of the four quadrants of any holon. Worldviews themselves find their natural home in the lower left or internal collective (IC) quadrant, as just stated. So the diagram below can be viewed as the four quadrants of any worldview: its consciousness, thoughts, and feelings, which are interior and individual, in that they are private (II); the public behavior associated with any worldview is exterior and individual (EI); the public relationships, by which others assess the applicability of this or that worldview is exterior and collective (EC); and the worldview itself, which is a value, belief system, and interpretation, is interior and collective (IC). Wilber's diagram provides an overview of broad characteristics associated with the various worldviews we will cover. Worldviews are collective scripts that define our Zeitgeist, the spirit of our time. They may not be our core identity, but they might as well be. Unless we objectify our worldviews they will define who we are. We not only identify with our worldviews; we are subjectively immersed and enmeshed with them to such a degree that they might as well be our identity. We will be prisoners of their groupthink. Even if we learn to objectify our worldviews, others will associate us with them, fairly or unfairly, whether we like it or not. To not recognize core elements of our worldview is to not know who we are in an objective way, as others who do not share our worldview see us. We will think we are autonomous agents, with little awareness of our our free choice is continuously conditioned and influenced by our worldview.

The Four Quadrants of Ken Wilber

What are the most likely characteristics of worldviews that humanity are evolving toward? Claims of clairvoyance aside, history and human experience are full of patterns that generate probabilities. In this series of essays we take a look at the historically ascendant priorities of major current civilizational worldviews - African/Global South, Western, Indian, Chinese, Russian, and that of artificial intelligence (AI). What might a socio-cultural integration of these worldviews look like in the exterior collective quadrant of human experience? In a final essay we will explore how phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism, as a form of polycentrism, can provide a foundation for an integrative, universal internal collective culture. Regarding the question of how our collective identity is most likely to reconstruct itself, we can list some of the more foundational characteristics of each of these worldviews and then ask, Which characteristics stand the tests of time? Which are most balanced/integrated across the four quadrants of the collective holon of humanity? Combining these measures will provide us with a guide for projecting the shape of our likely emerging collective worldview. Charts of each worldview provide an overview of priorities of these six different worldviews. On that basis we can make more likely predictions about emerging worldviews than if we merely rely on our ideological preferences, beliefs, or collective groupthink. Those predictions will still be wrong, but they will be less wrong and more likely to point us toward probable futures. “Lesser priorities”of various worldviews are not to be understood as unimportant in an axiological context. When there is a forced choice a higher priority is preferred. When there is no forced choice, “lesser priorities” often become the priority.

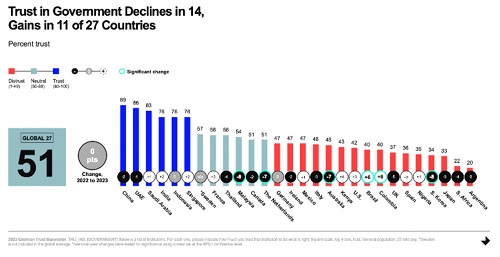

The inescapability of competing worldviews There currently exist global conditions where competing worldviews are forcing us to deal with them, regardless of our wishes, preferences, and beliefs. Due to our shrinking world in which we can communicate globally in real time and different worldviews increasingly impact our own in concrete ways, affecting our standard of living and income, we cannot afford to remain ignorant of alternative worldviews that differ from our own and that represent perspectives that refuse to be ignored or integrated into our worldview. Nor can we afford to make the common vision-logic, integral-aperspectival move of convincing ourselves that because we can map out other worldviews that we have no need to adapt ours to the territory they reveal. These pressures are increasing. For example, rising prices are forcing Europeans to the conclusion that they cannot maintain their lifestyles or society without Russian petrochemicals. They cannot ignore, buy off, or colonize the Russian, Chinese, and Global South worldviews. While the Western worldview can continue to maintain its belief in its superiority, in practice it is having to give ground to other worldviews. Those in the west whom have been called “the Golden Billion,” are being forced to consider that multiple alternative worldviews that challenge their own are equivalent or even superior in legitimacy. This is producing a profound and existential crisis of identity in the West. As the world becomes smaller and we all become more interconnected, what do we do when those who hold different worldviews and base their identities on different beliefs, axioms, or a priori assumptions than our own can no longer be ignored, written off or suppressed? Perhaps their impact can no longer be successfully ignored, as is the case when we are dependent on goods from China. Perhaps faux adoption or co-opting no longer works, as when we take on attributes of other worldviews that do not threaten our own, like learn Japanese origami or wear African prints. If ignoring or chameleon masking do not work to fend off the threat of another worldview to our own, a preferred option to giving up core aspects of our worldview that sustain our identity is colonization, a movement beyond denial and chameleon masking to repression. But what happens if we can no longer culturally, financially, or militarily neutralize worldviews that challenge our own? Historically, people have little to no reason to be interested in worldviews beyond their own, due in part to common, hard-wired cognitive biases of normalcy and frequency. We have good reason to assume that tomorrow will be pretty much like today and therefore doubt ideas and discount developments that question that assumption. We have good reason to believe that the habits that have had adaptive value to get us through yesterday will work to get us through today. Therefore, for the vast majority of humans, there is little adaptive or functional value in learning about other worldviews. Another built-in cognitive bias reinforces the hard-wired cognitive biases of normalcy and frequency, and that is a survival bias. To survive, we need to stay oriented toward time, place, and identity. To do so we integrate those experiences into our identity that have adaptive value while ignoring those worldviews that challenge our cognitive biases, or fight them because they threaten our sense of who we are and how we organize our experience. These sieves filter how we interpret alternative worldviews we discuss here. You will ask, “How likely am I to need this information?” “Does this other worldview support or threaten mine?” “If it challenges mine, can I successfully ignore it?” “If not, can I integrate it into my own in an act of conceptual colonialism?” Every worldview tends to imagine itself as most inclusive and therefore transcending others. That belief is something of a tautology. If I define my worldview as intrinsically inclusive and transcendent, then that will be the filter through which I evaluate the relative merits of every other worldview. I will keep that which fits into and supports my worldview while ignoring or discounting the rest. Those who accept my worldview are initiates, members of the elite, “sheep,” and those who don't are sleepwalkers, deplorables, “goats.” The result is that those who accept my worldview, which defines itself as all-inclusive, are likely to be fellow elitists and exceptionalists. And of course elitism and exceptionalism contradict multi-perspectivalism.[1] It is not an exaggeration to state that the Western worldview, including “the American Dream,” is the predominant worldview of the world today. Europe and the U.S. have successfully exported their societal models as democratic systems of governance around the world while Western culture has been envied, copied, and internalized worldwide, largely due to advantages of technology and to economic supremacy. At the same time, resistance to the Western worldview has often come at a very high price indeed. The American Dream is not only out of reach for many people globally but for increasing numbers of citizens of the west. Many people who identify with that worldview are challenging its assumptions and no longer accepting them. Trust in the Western worldview is plummeting while confidence in alternative worldviews is increasing.

As a consequence, those who identify with the Western worldview, which has dominated the world for the past five hundred years, are currently dealing with denial and anger, the first two stages of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross' Five Stages of Grief. This denial and anger is due to the collapse of economic, cultural, social, institutional, military, religious, and ideological assumptions which have served as the bedrock of Western identity. However, as of winter, 2023, the West is not yet ready to bargain with worldviews that challenge its own, and therefore is currently some time away from entering the last two stages of depression and acceptance. While it is entirely possible that the western media may once again successfully change the subject from the West's loss of military, economic, and informational wars with Russia and China, that is not the way current global events are playing out.[2] The West is increasingly unable to redirect awareness from unavoidable facts on the ground, including its ongoing de-industrialization, rising costs of energy and food, the collapse in services, currencies, and public trust. The collapse of a worldview with which we are closely identified risks the collapse of identity itself. The associated challenge is how to avoid an existential, PTSD-like death spiral into nihilism that takes down alternative worldviews with it. How will western publics respond to this ongoing collapse, once its reality sinks in? Will western publics react with anger out of a sense of betrayal by their governmental, social, and cultural institutions? Will they simply “move on,” shifting focus to the latest drama, as if the collapse never happened? Will they focus on creating decentralized alternative structures? What will be the elements of the pre-eminent global worldviews that will rise out of the ongoing collapse?

Assumptions of Integral/Metamodern worldviews

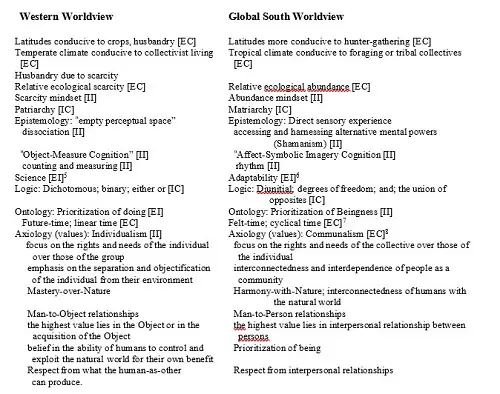

Metamodernism, which strives to form a higher order synthesis of modernism and post-modern worldviews, is an outgrowth and extension of an integral worldview.[3] Functionally, metamodernism is a form of integral, as it shares its fundamental premises. These include multi-perspectivalism, holons, and four quadrant analysis. Multi-perspectivalism attempts to honor and include multiple worldviews without descending into heterarchical relativism. Instead, it argues that priorities do matter, and that these are determined by both contexts and subjective immersion, or unawareness of how our worldview is conditioned by our own unrecognized assumptions and biases. Holons are parts which are also wholes and as such, are parts of greater wholes, or contexts. Holons have at least four different intrinsic perspectives or worldviews. Four quadrant analyses assess different worldviews and their priorities in terms of interior/exterior, individual/collective polarities and their integration. Does a particular worldview (or priority within that worldview) favor a particular quadrant? Which quadrant is most ignored or neglected? In the charts below of the priorities of different worldviews, I make my best guess at quadratic orientation by placing after the priority, in parenthesis, the quadrant (Interior Individual [II], Interior Collective [IC], Exterior Individual [EI], or Exterior Collective [EC]) that it seems most likely to be identified with. The further implication is that the opposite quadrant is most likely to be ignored or not integrated within it. For example, the Integral worldview is most strongly identified with the Internal Individual quadrant [II] due to its emphasis on self development, consciousness, and teleological (“spiritual”) explanations for evolution. It is weakest in the opposite quadrant, External Collective [EC], due to its lack of emphasis on justice, morality, and outgroup critiques. This shows up in its focus on higher relational exchanges and silence regarding issues of social justice, such as Western global terrorism, the pervasive corruption in the Western economic system, with which it maintains its dominant global privileges, and Israeli apartheid. As another example, worldviews are Interior Collective [IC] values, intentions, interpretations with which we identify [II]. They define who we are to ourselves. As such, the oppositional quadrants are Exterior Individual [EI] and Exterior Collective [EC]). We tend to identify with our values, beliefs, and intentions, and rationalize our behavior [EI] in terms of our worldview in order to reduce cognitive dissonance that threatens our identity. So if we lie, cheat, steal, or kill we identify with the justifications we create in our interior collective quadrant [IC]. Our worldview therefore exists as an adaptive mechanism to defend us from identity meltdown. Our core identity itself [II], is opposed to the “other,” “outgroups” [EC]). Non-assimilated oppositional relationships in that quadrant [EC]) are always present to create and sustain our overall holonic identity. When we imagine that our worldview “transcends and includes” other worldviews, that conclusion is based on a convenient avoidance of both our non-congruent behavior [EI] and the oppositional “other” [EC]), whatever, whomever it may be. Despite its incorporation of the Indian worldview, which we will explore in a subsequent essay, the integral worldview is an idealistic subset of the Western, not the Indian, worldview. There are several indicators of this. Conceptually, it is a child of Platonism, neo-Platonism, Hegel, and Whitehead. There is little in the Indian worldview that is incompatible with that foundation. In addition, there is nothing about the integral worldview which is intrinsically incompatible with the Western worldview. The integral perspective is also Western in the sense that integralists see no contradiction in voting for “progressive” and “liberal” politicians who wage unauthorized wars, support apartheid, ignore corporate and governmental corruption, authorize the arming, funding, and training of terrorists, and commit terrorist acts themselves. This can be taken as an indication of integralist/metamodern identification with the Western worldview.[4] While it is mistake to consider any of these worldviews “superior” or “inferior” to other worldviews, it is both reasonable and wise to assess the relative benefit of this or that priority in any worldview, depending on some set of concrete circumstances. By acknowledging the powerful influence of each of these worldviews we can then begin to consider what a broader “zone of confluence” might look like and how it is likely to shape future global culture and society. We can begin by looking at the Global South worldview, in comparison to the Eurocentric, Western worldview.

The above description of the African/Global South worldview draws heavily from the work of several African and black intellectuals, Cheik Anta Diop, Vernon J Dixon, Edwin J Nichols, and Karanja Keita Carroll, as related by Germane Marvel in his various essays on metamodernism from an African perspective.[9] Diop, a Senegalese historian, anthropologist, physicist, politician, and polyglot proposed a “Two Cradles” theory in The African Origins of Civilization. His model is essentially a comparison/contrast of underlying factors that have generated the African and Eurocentric worldviews, from an African perspective. The critique of these African authors is important not only for understanding why the Western worldview achieved and maintained global cultural dominance, but how that translated into social, behavioral, and psychological dominance of other worldviews, societies, and cultures. Such an understanding is a pre-requisite to arriving at a synthesis of the two that recognizes and builds on the strengths of each. Because many fundamental characteristics of the African worldview are not unique to Africa but are generally shared by the Global South, I have extended that theory and worldview beyond the intent of the authors, which was to define and establish an African/black worldview. Growing directly out of Diop's “Two Cradles” theory, the normative assumptions of a people summarize their perceptions of the nature of the 'good life' and the political, economic, and cultural forms and/or processes necessary for the realization of that life. A people's frame of reference, which is more directly related to academic disciplines and scientific inquiry, serves as the 'lens' through which people perceive the experiential world.[10] A cultural group's understanding of the universe (cosmology), being (ontology), values (axiology), reasoning (logic) and knowledge (epistemology), all contribute to the ways in which a people make sense of their lived reality, that is, their worldview. Growing directly out of their worldview, the normative assumptions of a people summarize their perceptions of the nature of the 'good life' and the political, economic, and cultural forms and/or processes necessary for the realization of that life. A people's frame of reference, which is more directly related to academic disciplines and scientific inquiry, serves as the 'lens' through which people perceive the experiential world. Regarding some latitudes being more conducive to hunter-gathering than others, Jared Diamond draws the following conclusion:

History followed different courses for different peoples because of differences among peoples' environments, not because of biological differences among peoples themselves.[11]

Tropical climates are more conducive to foraging or tribal collectives:

…the ferocity of nature in the Eurasian steppes, the barrenness of those regions” and “the overall circumstances of material conditions” all “were to create instincts necessary for survival in such an environment” and therefore led to a difference in worldview. One that would accommodate conditions where the archetypal mother, mother nature “left no illusion of kindliness: it was implacable and permitted no negligence; man must obtain his bread by his brow. Above all, in the course of a long, painful existence, he must learn to rely on himself alone, on his own possibilities. [13]

Due to greater average amounts of rainfall, warmer and non-extreme weather, tropical regions sustain a greater abundance of plant and animal life forms than do temperate zones.

Tropical regions show more biodiversity than temperate regions. The tropics receive direct sunlight, and therefore has higher temperature compared to other regions. This causes more evaporation, resulting in precipitation in the form of rain. Thus, there is a constant weather pattern in the tropics which is favourable for the growth of plants and animals. Tropical environments are, therefore, less seasonal, relatively more constant and predictable. This promotes niche specialisation and hence, greater biodiversity is seen in these regions.Additionally, the tropical regions remain relatively undisturbed for millions of years. Therefore, they have a longer evolutionary time for species diversification compared to temperate regions, which have experienced frequent glaciations in the past.[12]

The cradles of scarcity and abundance led to scarcity and abundance mindsets.

As Ife Amadiume (1987, 1997) has shown, the Southern Cradle correctly reflects a “matrifocal” social system.[14] Like all bipolar distinctions, this one is a generalization and stereotype, and while there is plenty of evidence that patriarchy is associated with Bronze Age culture in temperate societies, so was matriarchy. I know of no persuasive evidence that either tropical or hunter-gatherer societies were/are predominantly matriarchal. Diop notes that

Humanity has from the beginning been divided into two geographically distinct 'cradles' one of which was favorable to the flourishing of matriarchy and the other to that of patriarchy, and that these two systems encountered one another and even disputed with each other as different human societies, that in certain places they were superimposed on each other or even existed side by side.[15]

The Abundant Southern Cradle, with its many resources and a more temperate predictable climate, led to a matrilineal family structure in which the mother's side of the family played a central role in social and economic organization. This was due in part to the importance of agriculture, which required a significant investment of labor and resources, and was passed down through the female line as often as the male. The matrilineal structure also reflected a societal emphasis on communalism and harmony with nature, as well as a recognition of the central role that women played in both reproduction and the maintenance of social and economic systems.[16]

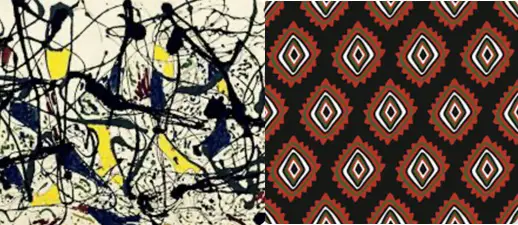

Epistemology refers to a group's beliefs about what can be known and how knowledge is acquired. Carroll describes the epistemological perspective of the Western worldview in terms of “empty perceptual space.” “I step back from phenomena, I reflect; I measure; I think; I know; and therefore I am and I feel.”[17] This is contrasted with African world view epistemology of direct sensory experience, in which “I feel phenomena; therefore I think; I know.”[18] In terms of epistemology, the abundance lens of the African worldview is said to be based on “Affect-Symbolic Imagery Cognition”, which emphasizes the role of emotions and symbols in understanding and interpreting the world. The scarcity lens, on the other hand, is said to be based on “Object-Measure Cognition”, which emphasizes the use of objective measurement and observation to understand the world.[19] The “accessing and harnessing alternative mental powers” is associated with varieties of shamanism. This is a distinction between objectivity and disidentification, on the one hand, and subjectivity, enmeshment, immersion, and identification on the other. According to Nichols, “[t]he European logic system has its basis in dichotomy, by which reality is expressed as either/or. African logic, however, is diunital, characterized by the union of opposites.” By contrast, African logic is Diunitial, involving degrees of freedom and the union of opposites.[20]

Ontology refers to a group's understanding of the nature of being or existence, as well as their beginnings.

The abundance lens is said to prioritize Being, or the present moment and the experience of being alive. In contrast, the scarcity lens is said to prioritize Doing, or the focus on future goals and accomplishments. The abundance lens in turn is said to prioritize Person-to-Person relationships, which emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of people as a community. In contrast, the scarcity lens is said to prioritize the Man-to-Object relationships, which emphasizes the separation and objectification of the individual from their environment.[21]

Axiology refers to a group's values and beliefs about what is valued and not valued, and eventually the nature of good and bad, right and wrong.

….the abundance lens also emphasizes communalism, or the importance of the community and harmony, while the scarcity lens prioritizes individualism, or the focus on the rights and needs of the individual over those of the group. Following on from this abundance lens is said to prioritize Harmony-with-Nature, or the belief in the interconnectedness of humans with the natural world. In contrast, the scarcity lens is said to prioritize Mastery-over-Nature, and the belief in the ability of humans to control and exploit the natural world for their own benefit. Respect on the one hand, the the abundant mode, comes from the interpersonal relationships as humans, and on the other hand, in the scarcity mode, from what the human-as-other can produce.[22]

The dominant value-orientations in the Euro-American world view is what I term the Man-to-Object relationship; while for homeland and overseas Africans, it is what I term the Man-to-Person relationship.[23]

Nichols argues that “[t]he European focus on Man-Object dictates that the highest value lies in the Object or in the acquisition of the Object.” as well as in interpersonal relationship between persons.

“[i]n [an] African axiology, the focus is on Man-Man. Here, the highest value lies in the interpersonal relationship between persons.”

The abundance lens is said to prioritize Being, or the present moment and the experience of being alive. In contrast, the scarcity lens is said to prioritize Doing, or the focus on future goals and accomplishments.[24]

According to Carrolls, in his assessment of Nichol's work, fundamental axiological difference between the two worldviews is clearly grounded within the relationship between the self and the other. Among Euro-Americans the value orientation is guided by

Doing, Future-time, Individualism and Mastery-over-Nature. Among African descendants, the value orientation of their worldview is based upon Being, Felt-time, Communalism and Harmony-with-Nature.[25]

Conclusion

Germane Marvel has brought together a very insightful assessment of the prevailing Western worldview from an African perspective for the purpose of generating a metamodern synthesis. While such comparisons and contrasts are generalities and stereotypical, as Stephen Pinker has pointed out in The Blank Slate, stereotypes have heuristic value and exist because they are generally correct. As such, each of these priorities can be demonstrated to be inexact, with contrasting examples in abundance. Therefore, they are best treated as food for thought and approximations directing us toward a higher order synthesis rather than as truths. This is a functional perspective from which to approach this and subsequent essays on worldviews. We will next consider some of the major characteristics of the Indian worldview, its compatibilities with both Western and Integral/metamodern worldviews, and consider how it is likely to fare within the rapidly evolving clash of multiple worldviews.

NOTES

|