|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Check out my other conversations with ChatGPT From Species to Life ItselfClimbing Down the Taxonomic LadderFrank Visser / Grok

Imagine standing at the top of a grand staircase, gazing down into the abyss of time. Each step represents a layer of life's complexity, from the bustling diversity of species we see today to the primordial spark that ignited existence itself. This is the taxonomic ladder—a metaphorical ascent (or descent, depending on your perspective) through the hierarchy of life, from the fine-grained branches of species and body plans to the broad roots of domains and the very origin of life. In popular discourse, evolution is often shorthand for Charles Darwin's revolutionary ideas, refined through the Modern Synthesis and now expanded into the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. But these represent only the uppermost rungs, the recent milestones in our understanding of how life adapts and diversifies. To truly climb—or rather, descend—this ladder, we must venture deeper into evolutionary history, guided by visionary scientists who have peeled back the layers of life's ancient narrative. Darwin's "Evolution 1.0" laid the foundation with natural selection as the engine of species diversification. The Modern Synthesis, or "Evolution 2.0," integrated this with Mendelian genetics, emphasizing gene mutations and population dynamics as the core mechanisms of change. Today, the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis—"Evolution 3.0"—broadens the canvas further, incorporating developmental plasticity, epigenetic inheritance, and niche construction, challenging the gene-centric view of its predecessor. Yet, these frameworks primarily address the "how" of recent evolution, the tweaks and tunes that shape organisms over generations. To grasp the "why" and "from whence" of life's grand architecture, we must descend further, exploring the origins of body plans, eukaryotic cells, microbial domains, and life itself. This journey isn't a rivalry of ideas but a chronological unfolding, each layer building on—or rather, predating—the next. Join me as we climb down, rung by rung, through the contributions of Charles Darwin, Sean B. Carroll, Lynn Margulis, Carl Woese, and Nick Lane. Charles Darwin: The Origin of SpeciesOur descent begins with the familiar yet profound: the origin of species. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, a book that shattered the static view of life and introduced a dynamic, branching tree of descent with modification. Darwin, a meticulous naturalist shaped by his voyage on the HMS Beagle, observed the subtle variations among Galápagos finches—beaks adapted for cracking seeds or probing flowers—and extrapolated a universal principle: natural selection. In a world of limited resources, individuals with advantageous traits survive and reproduce, passing those traits to offspring, gradually leading to new species. All life, he argued, descends from common ancestors, with diversity arising not from divine design but from the relentless sieve of survival.

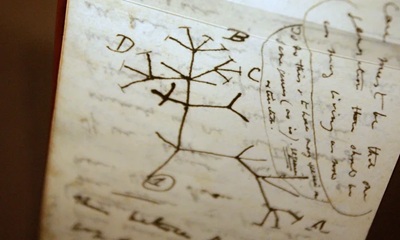

First sketch of the Tree of Life by Charles Darwin.

Picture a vast orchard where trees compete for sunlight; the tallest thrive, their seeds sprouting even taller progeny. Darwin's insight was revolutionary, explaining not just the finches but the myriad forms of life, from orchids to whales. Yet, his theory focused on the species level—the tips of the branches—without delving into how those branches first formed or how bodies themselves evolved their intricate plans. Darwin pondered the "mystery of mysteries" of speciation but left the deeper architectural origins for future explorers. His work set the stage for the Modern Synthesis in the 20th century, where geneticists like Ronald Fisher and Theodosius Dobzhansky wove in Mendel's laws, showing how mutations provide the raw material for selection. But to understand the blueprints of bodies, we must step down further. Sean B. Carroll: The Origin of Body PlansDescending the ladder, we encounter the enigma of body plans—the fundamental architectures that define animal phyla, from the segmented worms to the radial symmetry of starfish. Here, Sean B. Carroll, a pioneer in evolutionary developmental biology (evo-devo), illuminates how genetic toolkits shape these forms. In his seminal book Endless Forms Most Beautiful, Carroll reveals that the diversity of body plans arises not from inventing new genes but from tweaking the expression of ancient, conserved ones. At the heart of this is the Hox gene family, a set of "master control" genes that act like switches, dictating where limbs, eyes, or segments develop during embryogenesis.

Homeobox Genes in Embryogenesis and Pathogenesis

Think of it as a genetic orchestra: the same instruments (genes) play different symphonies depending on the conductor's cues. Carroll's work shows how small changes in regulatory DNA—regions that control when and where genes turn on—can lead to profound morphological shifts. For instance, the evolution of insect wings or vertebrate limbs stems from repurposing these toolkits, a process that unfolded during the Cambrian Explosion around 540 million years ago, when body plans diversified explosively. Evo-devo bridges Darwin's selection with developmental genetics, explaining why fruit flies can grow legs on their heads if Hox genes misfire, or how butterflies' wing patterns evolve through subtle tweaks. This layer predates speciation, focusing on the developmental scaffolding that allows species to vary. Yet, even body plans assume a eukaryotic canvas—complex cells with nuclei and organelles. To uncover that, we delve deeper. Lynn Margulis: The Origin of Kingdoms and EukaryotaFurther down the ladder lies the origin of eukaryotic cells, the building blocks of all multicellular life, including the kingdoms of animals, plants, fungi, and protists. Lynn Margulis, a bold microbiologist, revolutionized this understanding with her theory of symbiogenesis—the idea that eukaryotes arose not through gradual mutations but through symbiotic mergers of prokaryotic cells. In the 1960s, Margulis proposed that mitochondria (the powerhouses of cells) and chloroplasts (photosynthetic engines in plants) were once free-living bacteria engulfed by host cells, forming a mutualistic partnership that became inseparable.

In the theory of symbiogenesis, a merger of an archaean and an aerobic bacterium created the eukaryotes, with aerobic mitochondria; a second merger added chloroplasts, creating the green plants.

Envision a cellular potluck: an archaeal host swallows an aerobic bacterium, which survives inside, providing energy in exchange for protection. Over eons, genes transfer, and the duo evolves into a single entity—the eukaryote. This happened around 2 billion years ago, enabling the energy surplus needed for larger, more complex cells. Margulis extended this to the four eukaryotic kingdoms, arguing that serial endosymbioses sculpted life's diversity beyond bacteria. Initially dismissed as heresy against Darwinian gradualism, her ideas gained traction with genetic evidence showing mitochondrial DNA's bacterial roots. Symbiogenesis complements natural selection; it's not a rival but a mechanism for major transitions, like the leap from single cells to multicellularity. But eukaryotes are just one branch—what of the prokaryotic world that birthed them? Carl Woese: The Origin of Bacterial DomainsDescending yet further, we reach the microbial foundations: the domains of life. Carl Woese, using molecular phylogenetics in the 1970s, upended the five-kingdom model by revealing three fundamental domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Analyzing ribosomal RNA sequences—molecular fossils conserved across life—Woese showed that archaea, once lumped with bacteria, form a distinct lineage, often thriving in extreme environments like hot springs.

A phylogenetic tree based on rRNA data, emphasizing the separation of bacteria, archaea, and eukarya as proposed by Carl Woese et al. in 1990,[1] with the hypothetical last universal common ancestor

This was like redrawing the map of Earth to include a hidden continent. Bacteria and archaea dominate the planet's biomass, with eukaryotes as a latecomer twig. Woese's tree of life places the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) at the root, from which bacteria and archaea diverged early, and eukaryotes emerged from an archaeal-bacterial fusion—echoing Margulis. This domain-level view, dating back over 3.5 billion years, highlights prokaryotes' role in Earth's biogeochemistry, from nitrogen fixation to oxygen production. It reminds us that life's story is mostly microscopic, with macro-evolution as a recent flourish. But how did these domains arise from non-life? Nick Lane: The Origin of Life ItselfAt the ladder's base lies the ultimate question: the origin of life. Biochemist Nick Lane posits that life emerged in alkaline hydrothermal vents on the ancient ocean floor, where geochemical energy gradients drove the first metabolic reactions. In books like The Vital Question, Lane argues that proton gradients—electrical charges across membranes—were key, mirroring modern cells' energy production. These vents, with porous mineral cells, provided natural reactors for organic synthesis, bridging geochemistry and biology.

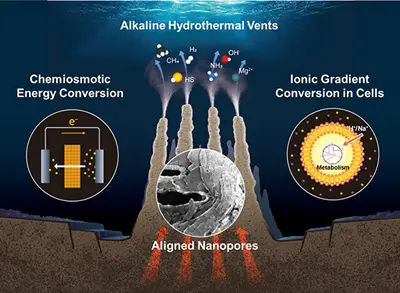

A deep-sea hydrothermal vent with aligned nanopores enabling selective ion transport and ion gradient energy conversion.

Visualize a submarine volcano spewing alkaline fluids into acidic seas, creating a fizz of energy like a natural battery. Here, around 4 billion years ago, RNA-like molecules and primitive metabolism could form before genes or cells proper. Lane's theory integrates metabolism-first views, explaining why all life shares ATP as energy currency and why complex life is rare—requiring that eukaryotic endosymbiosis for energy scaling. This bottom-up perspective grounds evolution in physics and chemistry, closing the loop from life's spark to its diversification. Conclusion: Beyond Superficial SynthesesClimbing down this taxonomic ladder reveals evolution not as a single theory but a tapestry of milestones, each addressing deeper strata of life's history. From Darwin's species to Lane's primordial vents, we see a continuum where selection, development, symbiosis, phylogeny, and bioenergetics interweave. This framework, suggested in Frank Visser's 2020 Integral Review paper "Ken Wilber's Problematic Relation to Science," critiques integral theorist Ken Wilber's superficial engagement with these fields.[1] Wilber, while aspiring to synthesize science and spirituality, often misrepresents evolutionary biology, favoring metaphysical narratives over empirical depth—ignoring evo-devo's genetic insights or symbiogenesis's cooperative leaps. True integration demands grappling with these layers, not glossing over them. As we ascend back to the present, enriched by this descent, we're reminded: life's ladder is vast, and climbing it requires curiosity, rigor, and a willingness to embrace the depths. NOTES[1] Frank Visser, "Ken Wilber's Problematic Relationship to Science", Integral Review, August 2020 Vol. 16, No. 2, p. 167-185.

Comment Form is loading comments...

|