|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY FRANK VISSER

Wilber vs. Coyne

On The Conflict Between Science and Religion

and the (Im)possibility of a Resolution

Frank Visser

Living with uncertainty is hard for many people, and [this] is one of the reasons why people prefer religious truths that are presented as absolute.

—Jerry Coyne, Faith vs. Fact, p. 37.

Jerry Coyne, evolutionary geneticist

Jerry Coyne, evolutionary geneticist

Jerry Coyne, professor in the department of ecology and evolution at Chicago University and specialized in evolutionary genetics, counts as a hard-nosed defender of neo-Darwinism, against assaults from the field of religions and spirituality. As an atheist he's in the company of the New Atheists, sometimes called the Four Horsemen, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett (the fourth one, Christopher Hitchens, recently died). Around the Darwin celebration year he published Why Evolution is True (2009). Recently a new book came out from his hand: Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible (2015). Coyne argues that "accommodationism", the belief that science and religion can be reconciled, fails for many reasons. In his opinion, religion has increasingly lost ground to science, and will do so even more in the future, because science is simply the best method to discover facts about reality.

It is instructive to compare this work to Ken Wilber's The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and Religion published in 1998, which has not had a great effect on the science vs. religion debate, and which defends the opposite thesis. Wilber, of course, takes up the defense of spirituality (though not of the fundamentalist kind), and proposes if not an accommodation then at least an "integration" within a larger scheme of these two main human quests for truth and meaning. Wilber would agree with Coyne that, confronted with a choice between mythic-fundamentalistic religion and rational-materialistic science, science would win out as the best means to explore and explain the natural world (Coyne's thesis). But he counters that there are deeper versions of both science (non-materialistic) and religion (non-fundamentalistic), which changes the picture dramatically. In this larger view, mythic religion and materialistic science are both stage-specific expressions within a larger developmental scheme, with other stages both preceding (e.g. magic) and following (e.g. mysticism) them.

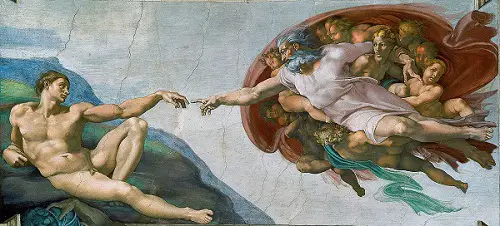

Critics of religion (e.g. Dawkins) often are met with the objection that they focus on dogmatic forms of religion more sophisticated theologians have long left behind. So it is fine to argue that God as the Man with the Beard in the Sky doesn't exist, but what about more subtle understandings of spiritual reality? Coyne specifically addresses this objection, which is relevant for the validity of Wilber's theory. This is all the more the case because Wilber has started to brand his view of spirituality as "evolutionary", which makes it a prime candidate for analysis in the context of the science vs. religion debate. Has Wilber presented a view of evolution which, as he usually claims, "transcends-and-includes" the conventional materialistic view of evolution? We have often argued that, instead of including evolutionary theory, Wilber has distorted it beyond recognition in his hurry to present a transcendental view of evolution. How would Wilber's proposal be classified within this wider discussion?

Wilber would fall into the category of "theistic evolutionism", even if his theology would be decidedly more mystical than most versions we find today.

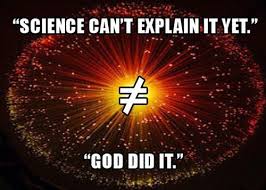

Wilber would fall into the category of "theistic evolutionism", even if his theology would be decidedly more mystical than most versions we find today. In Wilber's opinion, evolution (and human history, for that matter) is driven by Spirit—usually called "Eros". This presumably explains the, otherwise unexplainable, fact that in the long course of biological evolution, organisms have become more and more complex and conscious. So the concept of Spirit is explicitly brought into the picture to explain complexities of nature that would otherwise defy any comprehension. Scientists, of course, beg to differ, and argue that science progresses step by step in its quest to unravel the mysteries of nature. That science doesn't know all the answers yet is not a problem, nor does this imply that other disciplines (such as integral philosophy) would be qualified to provide these answers. Dawkins, for one, would call these mystical speculations "empty obscurantism", a term he uses on the back cover of Coyne's book to qualify the pretensions of sophisticated theologians.

Coyne's thesis, on the other hand, might superficially be read as the trivial claim that religion is not as good as science when it comes to explaining reality. What if religion has other goals than explaining the world? True, the Bible is not really a science book, but creationist theologians do make statements about the age of the earth and the cosmos, or the possibility of miracle cures. And, one might add, Wilber does claim that it is Spirit/Eros that is operative in the biological processes such as human immunity or speciation in general (Coyne's field of expertise). As Wilber wrote in a blog posting "Some Criticisms of My Understanding of Evolution" some years ago:

[T]here is a force of self-organization built into the universe, and this force (or Eros by any name) is responsible for at least part of the emergence of complex forms that we see in evolution. (www.kenwilber.com, December 04, 2007)

The biggest weakness here, as I have argued elsewhere, is that Wilber has never specified for which part of biological complexity this Eros is responsible. Here he is, of course, in the same predicament as the many authors of the Intelligent Design variety (such as Michael Behe), who imply the Hand of God without every getting specific. It is a pity that Wilber has never engaged competent evolutionary theorists directly—even if only in writing—when arguing for his particular take on evolution.

Coyne, for one, co-authored a famous handbook on speciation (Speciation, 2005). Would he agree with Wilber's suggestion that it is impossible to explain this evolutionary phenomenon without the intervention of Spirit? Of course, he wouldn't. Vague references to "creativity in nature" don't count as explanations in science.

To those theologians (like Alvin Plantinga) who argue for a Divine influence in evolution, Coyne states:

[T]heistic evolution makes a common error of accommodationism: confusing logical possibilities with probabilities. Yes, it is logically possible either that God started the evolutionary process, created the first organism, and then stood back to watch the action, or that he intervened from time to time, creating new organisms or mutations. But from what we know about evolution, that's unlikely. The process shows every sign of being naturalistic, material, unguided and lacking divine assistance. (p. 150)

This, however, is exactly what is contested by spiritualists like Wilber. Again and again he has argued that the complexities of nature cannot possibly have been evolved through "chance" alone: be it the molecules of enzymes, the origin of bird wings or the intricacies of the human immune system. In the end, the conflict of science and religion is a battle of probabilities. What doesn't help is that Wilber doesn't make a clear distinction between random mutations and non-random selection—an elementary distinction in evolutionary theory. In this way at least a case can be made that natural selection can create complexities adapted to their own circumstances. Arguing that science sees everything as just a game of chance is a strawman argument if every there was one.

What is more, there's a slightly impractical side to this spiritual point of view. Do these religionists really believe that the Spirit of the Cosmos has intervened in the DNA of organisms to steer speciation one way or another? Really? A single visit to a local planetarium should cure one of these provincialist beliefs. We are simply lost in an orgy of billions of galaxies, within billions of clusters and super clusters of galaxies. From a cosmic point of view, our quite ordinary Sun isn't even visible, let alone planet Earth, not to mention the fact that tinkering with millions of genes in millions of species at millions of moments in time is quite a logistic task to perform, even for an omnipotent God.

DIVINE INTERVENTIONS: IF, WHEN, HOW?

For Coyne all these religious speculations are nothing but religious "add-ons", adding no insight whatsoever.

Wilber's view of spiritual evolution involves an active view of Spirit. Traditional views might picture Spirit as the Ground of Being, which doesn't interfere with the world and which can be contacted by introspective meditation. Not so for Wilber. His view of Spirit is an active one: he calls his view "evolutionary spirituality", implying that Spirit is intimately involved in the currents of evolution and history. This inspiring view makes it vulnerable for verification or falsification by science. If Spirit really makes a difference in the world, it should be possible to pinpoint exactly where Spirit has intervened in the processes of nature. We haven't heard from Wilber any believable suggestions.

In integral parlance, Jerry Coyne would be called a flatlander, stage absolutist and a scientistic reductionist. Does he see any value in religion at all? He opposes the famous doctrine of Stephen Jay Gould called "non-overlapping magisteria", meaning that science and religion, fact and value, belonged to two separate realms which didn't interfere with eachother. This "accommodationism" didn't mean that science and religion were compatible, only that they never entered the same territory to quarrel in the first place. Coyne states that religion (especially in the US) does enter the territory of science with its claims about the origin of cosmos, the first human beings and the age of the earth. Liberal theology has conceded these topics to science long time ago. The battle seems to be between conservative theology and science only.

But Coyne also opposes the accommodationism found among liberal religions believers. He suspects opportunistic motives among scientists, who embrace this accommodationism, because it would ensure funding from organizations such as the John Templeton Foundation, which has a yearly budget five times that of the budget available for research in evolutionary biology alone, and which has a very active PR department placing full page ads in The New York Times signed by noted scholars. It issues a Templeton Prize which exceeds the Nobel Prize in value. (I recall Wilber was once offered this Templeton Prize around 1997 but he declined, for reasons unclear to me, given his recent publication of The Marriage of Sense and Soul). Its biggest grant so far—$10.5 million over five years—went to a study titled "Foundational Questions in Evolutionary Biology". Coyne suspects a religious agenda here too, given that this study explicitly included non-scientific notions such as teleology and purpose in evolution (p. 18).

For Coyne, it's the facts that count. But what are facts? Water is H2O only in a rational-scientific worldspace. In a mythical-religious worldspace it could be holy water. Within its own worldspace, both are true facts. Given the developmental nature of his model, Wilber could even concede that the theories of science are "more true" than those of mythic religion. But his model also implies there are post-rational worldspaces to explore, lets call them "spiritual" for the moment. What would water look like from a spiritual worldspace? Would it be presented as the result of a "creative advance into novelty"? What insight would that give us? Does a spiritual view of evolution really transcend-and-include the scientific theory of natural selection? And what would it bring to the table: "a force of self-organization built into the universe"? What evidence would substantiate such a notion, and what would cause it to be falsified? But these are, again, rational-scientific methods of finding truth. The spiritual method would be: "this is my vision, take it or leave it"? Wilber explicitly claims to be talking from the stage/standpoint of "vision-logic".

We have two "cross-level debates" here: that of mythic-religion vs. rational-science and that of rational-science vs. vision-logic. Wilber's treatment of evolutionary theories and facts in his two dozen works hasn't been of such a quality that one would put faith in this vision-logic. Rather than transcend-and-include he has often displayed a transcend-and-distort mentality when it comes to representing the views from evolutionary science. How otherwise could he have blundered so often in his claims that neo-Darwinism has not been able to explain the evolution of eyes and wings, or the human immune system, or the processes of speciation?

John Haught, "evolutionary creationist"

John Haught, "evolutionary creationist"

Some second-generation integralists like Steve McIntosh and Carter Phipps, both reviewed on Integral World, have joined company with evolutionary theologians (such as John Haught) and other so-called "evolutionaries" to promote the idea of a spirit-driven evolution. For them, chapter 4 of Coyne's book ("Faith Strikes Back") is instructive reading. How do their arguments regarding the supposed failure of neo-Darwinism to explain the phenomena of evolution resemble those of theistic evolutionists or even creationists? And where do they differ? And how does a "flatland-reductionist" like Coyne respond to these arguments?

What has Coyne to say about theistic evolution, the view that evolution is "guided by God", as he phrases it, the view that "infuses religion into science" (see p. 132-140)? These theologians often pay lipservice to Darwinism by acknowledging the evolution of animal species with the exception of the human species, which is supposed to be a special creation, perhaps not as to the human body but for sure as to his soul (the official view of Catholicism). Apparently, religion goes along with Darwin's The Origin of Species but halts at his The Descent of Man... To an evolutionary biologist, human beings are of course technically speaking "African apes" (Dawkins). Coyne's reply to these attempt at human "exceptionalism" when it comes to us humans is typical for his sober outlook on life: "[A]ll the evidence points to unguided evolution, and even if that's distressing, it's the best inference we have. After all, we have to accept lots of things we don't like, including our own mortality." (p. 135)

Theologian and former physicist Ian Barbour's summary would certainly be acceptable to Wilber and other integralists:

The world of molecules evidently has an inherent tendency to move towards emergent complexity, life and consciousness (When Science Meets Religion, p. 164, quoted in Coyne, p. 136)

Theologians of this variety differ on the question if, when and how often God has interfered with the natural processes. On one end of the spectrum are Deists, who see no role for God once he has created the world. We've heard Ervin Lazlo say as much in his "Evolution Presupposes Design: Why the Controversy?" article in The Huffington Post: "Given the right preconditions, nature comes up with the products on her own." God has set the stage for natural selection to take over.

Coyne: ‘our universe is almost completely in-

Coyne: ‘our universe is almost completely in-

hospitable to any kind of life we know.’ (p. 164)

The whole cosmic fine-tuning discussion belongs here, of course: the idea that the cosmos somehow seems fine-tuned for life to evolve. Was gravity a tiny bit stronger or weaker, or was the value of the electron a tiny bit different, we wouldn't have been here. The list of "happy coincidences" is extremely long: some say the number of fine-tuned parameters found essential for life on a planet has risen to 200! Some physicists see this as proof for God's existence. Coyne is not that impressed by these arguments: ‘our universe is almost completely inhospitable to any kind of life we know.’ (p. 164). So we are just very lucky to live on this pleasant planet Earth, an an otherwise inhospitable universe. A refreshing view, considering that if Someone had fine-tuned these 200 parameters on His Cosmic Dashboard about 14 billion years ago, why did it take another 10 billion years before we had something like a habitable Earth? Not to mention the billions of years it took to create something resembling multicellular life. Something wasn't quite right with that Dashboard one would say...

Others see a role for God also during the process of cosmic evolution. Some see the origin of life as such an event, or the emergence of mind in humans—these are seen as events that are "ontologically discontinuous". Others go much further and sense the hand of God in such "irreducibly complex" phenomena as the blood clotting system of vertebrates or the whiplike tails (flagella) that propel some bacteria. Again, there are those that see a divine influence spread out over the whole process: God is equated with the "creativity" seen as inherent in nature.

Where does Wilber stand in this spectrum of possibilities? His defense of Michael Behe (author of Darwin's Black Box, 1996) and his reference to eyes and wings as major obstacles for a naturalist explanation (in A Brief History of Everything) puts him practically in the same camp as the Intelligent Designers or creationists. What typically happens here is that when scientists demonstrate that these phenomena allow for a naturalist explanation after all, either another complex natural phenomenon is chosen as proof for divine intervention (e.g. the human immune system in Wilber's case), or they retreat tactically to the position that God is inherent in the process of evolution, without any further specification. Hence Wilber's frequent confident assertions that "there is plenty of room for a Kosmos of Eros" (Integral Spirituality, p. 236n.), which sounds very religious but doesn't require—how convenient—any further specific evidence. Wilber believes, as he is fond of saying, that "the universe is slightly tilted toward self-organizing processes".

Again, a practical problem arises which is never answered: How would a cosmic "tilt" be effective in producing eyes and wings? Or new species? Or the human brain? Or mind? Or life? Or atoms? Is it active as a natural force, like gravity and electromagnetism? If so, what is its strength? Or relative weakness (as in "slightly tilted")? Why does it fail on other planets than our Earth to produce life and mind, not to mention the other solar systems and galaxies we are now trying to understand through space telescopes? Anyone?

For Coyne all these religious speculations are nothing but religious "add-ons", adding no insight whatsoever. He has coined the term "religionism" for it, the equivalent of the much wider known "scientism" (p. 201)—a overstepping of boundaries and claiming insight and authority where it doesn't really exist.

To the popular notion that evolution necessarily means an increase in complexity, Coyne follows essentially Stephen Jay Gould's argument:

Evolutionary biologists long ago abandoned the notion that there is an inevitable evolutionary march toward greater complexity, a march culminating in humans. If one considers all species together, the average complexity of organisms has certainly increased over the 3.5 billion years of evolution, but that's just because life began as a simple replicating molecule, and the only way to go from there is to become more complex. (p. 138-139)

Integralists would do well to engage these arguments by Gould, Coyne and others before they embark on their "onwards and upwards" view of natural and cultural evolution. Unfortunately, neither Wilber nor other integral "evolutionaries" have displayed any diligence in studying this field of science before claiming to have transcended it.

SCIENCE THE ONLY ANSWER

For sure, Coyne is no fan of religion, as he writes "religion is to science as superstition is to reason" (p. 258). And he concludes by appealing to the reason of his readers:

In the end, why isn't it better to find out how the world really works instead of making up stories about it, or accepting stories concocted centuries ago? And if we don't know the answers, why shouldn't we simply admit that we don't know, as scientists do regularly, and keep looking for answers using evidence and reason? Isn't it time that we take to heart the Apostle Paul's advice to the Corinthians to grow up and put away our childish things? Every obeisance we pay to faith buttresses those faiths that do real damage to our species and our planet. (p. 260)

Clearly, for Coyne then, a world without faith—understood as belief without evidence, which includes any superstition or ideology—would be a better world. He points to Europe to prove that less religiosity doesn't result in more immorality, as many devout US Christians fear. Given the wide rejection of evolutionary theory in the US, he considers most of his fellow Americans to intellectually still live in the Dark Ages. He is pessimistic about the value of religious faith, and in de final chapter highlights what he sees as its main negative impacts: child abuse, suppression of research and vaccination, opposition to assisted dying, and global warming denialism. Obviously, for Coyne there can't be any dialogue between religion and science, there is only the monologue of science that religion should listen to, as far as he is concerned.

[I]s it possible to have a constructive dialogue? My response is that anything useful will come from a monologue—one in which science does all the talking and religion the listening. Further, the monologue will be constructive for only the listener. While scientists can learn more about the nature of belief by talking to the faithful, those benefits can accrue to anyone who wants to learn more about religion. In contrast, religion has nothing to tell the scientists that can improve their trade. Indeed, the progress of science has required shedding all the vestiges of religion, whether those be the beliefs themselves or religious methods of finding "truth". We do not need those hypotheses." (p. 257)

A rich and stimulating book for those who value religion and are captivated by the integral message of evolution and spirituality, and are under the impression that they are up to date on science. It's way too easy to argue that "science is, like religion, a belief too" or "science has also resulted in bad things like the atomic bomb" or "we need religion to provide cohesion to society" or "we should't blame the Islam for IS". Coyne's refutations to these religionist claims are convincing and might require most religionists—including integralists—to reconsider their position regarding the compatibility of science and religion and the value of religion in general.

|

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020).

Comments