|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected] Dr. Joseph Dillard is a psychotherapist with over forty year's clinical experience treating individual, couple, and family issues. Dr. Dillard also has extensive experience with pain management and meditation training. The creator of Integral Deep Listening (IDL), Dr. Dillard is the author of over ten books on IDL, dreaming, nightmares, and meditation. He lives in Berlin, Germany. See: integraldeeplistening.com and his YouTube channel. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

SEE MORE ESSAYS WRITTEN BY JOSEPH DILLARD Characteristics of Our Emerging WorldviewPart 6-2: Characteristics of the Intrasocial WorldviewJoseph DillardSome Characteristics of Interviewed Intrasocial Elements Contrasted with Waking IdentityAll worldviews are manifestations of interior collective (IC) holonic quadrants because they are theoretical, interpretive belief systems that reflect individual and collective norms and values. They are also cognitive schemas by which we define ourselves and upon which we base large portions of our identities. While the other worldviews we have discussed in previous essays in this series are held by waking selves and the groups with which those waking selves identify, intrasocial worldviews are held by imaginal, subjective “others” and the groups with which they identify. These include dream, mystical, near death, and life issue elements, such as a fire personifying our anger or an axe personifying the source of a splitting headache. This is a worldview that is not based in the individual quadrants as a manifestation of waking priorities, but rather on collective, yet interior, multi-perspectivalism. Waking worldviews, such as those I have addressed in previous essays, assume they include and transcend non-waking or imaginal worldviews. Do they? How do we know? How can we know unless we explore the worldviews of such perspectives? The intrasocial also includes waking and historical events as “pictured” in our own minds. It is, of course, exactly on dream and mystical experiences that subtle, causal, non-dual, spiritual, and transpersonal worldviews, such as that proposed by Wilber in his “The Religion of Tomorrow,” are anchored and built. Therefore, establishing the reality and province of these experiences is highly relevant to any integral or metamodern worldview.

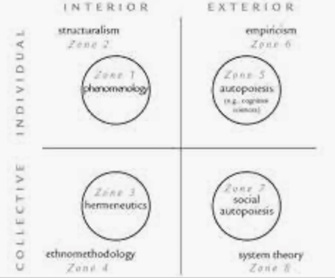

In Part 1 I explained what an intrasocial worldview is, contrasted its priorities with those of our ordinary, waking worldviews, and explained some of the reasons why an intrasocial worldview garners little awareness or attention. Chief among these is that there has not existed a methodology for revealing intrasocial worldviews. While shamanism, ancient Greek Muses, trance-channeling oracles, spiritualism, Tibetan deity yoga, Gestalt, Jungian shadow work, Wilber's 3-2-1 Shadow Work, possession, and multiple personality disorder all prefigure an intrasocial worldview in one way or another, they easily lead to mistaken and unhelpful characterizations about it.[1] This is because “waking,” or “objective” worldviews generally question individual rather than group “others,” whether deemed imaginal or real. Even obvious collectives, like a flock of sheep or a nation, are treated as individuals and interviewed as one entity. Individual encounters lead to either the conclusion that such elements are self-generated or to a dualism in which some, like mystical experiences, are objective and real, while the vast majority of encounters are considered to be internally produced and dreamlike. To reveal the intrasocial dimension a methodology that accesses multiple interior perspectives is required, for example, one that interviews multiple sheep in a flock or multiple individuals representing different groups in a nation. Group imaginal experiences that can be interviewed include mass “hallucinations,” misperceptions, such as economic bubbles and Ponzi schemes, as well as simple group social and cultural perceptions, such as groupthink and worldviews. Such perspectives are not necessarily interior or imaginal in that the worldview revealed may correlate with a waking, “real” worldview. An intrasocial methodology allows different imaginal perspectives to be compared to our waking worldview and to the perceptions of others to assess just how different and objective, or similar and subjective, they actually are. While Western and other worldviews we have considered in previous essays exist as varieties of psychological geocentrism to justify selves and their choices, intrasocial worldviews orbit around non-self collectives. These interviewed perspectives commonly show remarkable detachment from waking concerns, issues, and worldviews. There is a huge and fundamental difference between psychological geocentrism, the foundation of waking worldviews, and the polycentrism demonstrated by such groups. I have approached the worldviews we have previously considered through the lens of integral/ metamodernism, which assumes the multi-perspectivalism of map making, that “the cognitive line leads,” the integration of modernism and post-modernism. Intrasocial realities in the interior collective quadrant require examination through a lens that breaks from these assumptions. Its multi-perspectivalism is experiential rather than cognitive, in that it involves actually becoming perspectives rather than analyzing and comparing different perspectives. An intrasocial worldview is phenomenological in that it consciously attempts to surface such assumptions and lay them aside during the identification process, when you actually attempt to embody this or that perspective. It is polycentric, accessing the perspectives of an unlimited number of interviewed imaginal emerging potentials, rather than a psychologically geocentric approach, relying on the perspectives of personal and collective groupthink. While psychological geocentrism, the experience that we are the center of our reality, integrates information around and into our self sense, whether it be ego, vision-logic, transpersonal, Self, or non-dual, in a process Jung called “individuation,” polycentrism is more like a hologram, in which every point is the center of reality and a wormhole to every other point, containing the whole. For intrasocial worldviews, there exists no one reality around which everything is organized. Self, oneness, wholeness, soul, and spirituality are not underlying assumptions. The necessity of both geocentrism and polycentrism are other underlying assumptions to be set aside during the interviewing process. Just as the preponderance of both sensory data and common sense spoke for a Ptolemaic, earth-centered worldview before the invention of the telescope, so the majority of psychological and common sense data currently supports a psychologically geocentric worldview. What has been missing is a methodology, analogous to that of a telescope or microscope, to disclose the equivalent of macro- and microcosmic realities. Polycentrism becomes a testable antidote for the chronic human over-reliance on psychological geocentrism and the worldviews that justify it. Dream Sociometry, a methodology to disclose the intrasocial worldview, is a step in that direction, and I will be explaining it below. What is a phenomenological approach to multi-perspectivalism?According to Wilber's integral methodological pluralism, each of the four quadrants of every holon has an outer facing, objective, observable face and an inner facing, subjective, private face. This private face can only be known by undertaking an experiential identification with that perspective, which necessarily involves disidentifying with one's own perspective and taking up that which is intrinsic to the subjective reality of that quadrant. This is the core of any phenomenalistic methodology. Setting aside our assumptions is one aspect of that process. For the exterior individual quadrant, a phenomenological approach requires that we take up and act out behaviors that are reflective of the holon under consideration. While this could involve taking on the countenance and actions of a god, demon, or dream character, in something similar to shamanic possession, an embodied perspective is much more likely to express itself energetically, as a felt presence that can sometimes feel positively transcendent and other-worldly.

Integral Academy

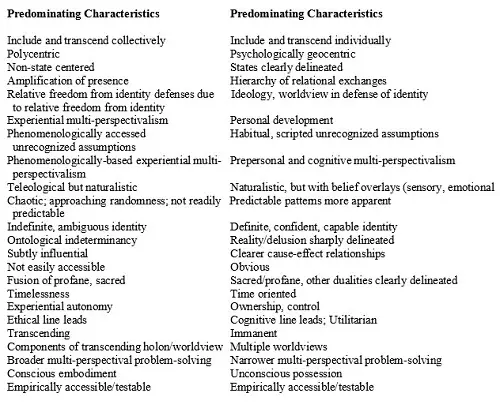

In what follows characteristics of the intrasocial worldview are compared/contrasted with those of normal, waking worldviews such as those we have surveyed in previous essays:

Exploration of the intrasocial is a form of dream yoga, a transpersonal discipline of the subtle realms. It reveals worldviews that are reflected by the priorities of interviewed perspectives that are emerging potentials, in that they are rarely recognized or understood until interviewed, but which nonetheless are found to embody authentic and generally realistic reframings of life priorities in ways that include, yet transcend, our own. The priorities of multiple interviewed perspectives, when taken together, form patterns of priorities which are theorized to represent those of a hypothetical “life compass,” which embodies fundamental or core priorities that are attempting to emerge in one's life. Include and Transcend Collectively/Include and Transcend IndividuallyWaking inclusion and transcendence is apparent in how we learn by building on top of foundational subsystems, for example, the rules of grammar necessary to build sentences and learn to think, crawling before walking, or fundamental arithmetic functions before algebra or calculus. The problem is that we typically stop including and transcending once we develop an investment in the stability and adaptability of the status quo, whatever habit, addiction, relationship, religion, national identity, or worldview we might identify with. In fact, we typically invest increasing amounts of energy in maintaining the stability and control inherent in the status quo and repel, by various means, information and experiences that are incongruent, or which create cognitive dissonance. The ongoing result is a slow, steady fossilization in various habits, addictions, dogmas, expectations, assumptions, rationalizations, and justifications. Further inclusion is shut down, and with it, possibilities for transcendence are reduced. What we are left with is the conviction, based on intent, that our worldview includes and transcends others, when in fact, multiple outgroups, both in the exterior and interior collective quadrants, beg to differ. This is where the sort of inclusion and transcendence provided by an intrasocial worldview comes in. Because the intrasocial worldview is disclosed by experiencing and comparing the perspectives of multiple elements that share some context, such as a mystical experience, life drama, nightmare, or work problem, a means of interviewing multiple perspectives is necessary. Intrasocial perspectives are not based on waking priorities, although they may in many instances align with them. While simply interviewing one will give you an inclusive perspective, since these emerging potentials are to a greater or lesser degree self-aspects, they may simply reflect your own assumptions and problem solving and therefore not transcend them or your own identity. However, one generally finds that these reframings are broader and more inclusive than our own. Interviewing multiple characters provides a greater likelihood of encountering not only perspectives that include and transcend our own, but also provide different recommendations which can be used to test their relevance and the validity of the methodology. Collective inclusion and transcendence is not more important than individual efforts to do so. What is required for a balanced life is bringing both of these into focus and emphasizing each in contexts in which one or the other is most effective. This is generally lacking or absent in humanity, which for reasons of personal development focus on early and often the securing of lower relational exchanges like security, safety, control, power, and status over the course of one's entire lifetime. We typically lack a polyperspectival perspective that arises out of identification with and appreciation and respect for non-group social and intrasocial perspectives. The balancing of these two, which provide something of a thesis/antithesis dialectic relationship to one another, can produce a higher order synthesis or transformation that we as individuals and we as collective humanity very much need but rarely access. Polycentric/Psychologically geocentricInterviewed imaginal elements are distributed and non-centralized in comparison to waking identity, which revolves around a self defined by its time, place, scripting, assumptions, beliefs, and competencies, but most importantly by its needs for survival, adaptation, and development. Psychological geocentrism is the assumption, validated by our senses, emotions, and justifications, that our identity, relationships, and world orbit around our identity and worldview. Problems arise because our identity is partial, in that it not only does not include alternative perspectives, but actively defends itself from perspectives it experiences as “not-self,” or “outgroup.” The result is that we find ourselves in conflict with a great deal of experience that in reality is not only not a threat, but which we need in order to heal, balance, and transform. An elaboration or sub-category of psychological geocentrism is psychological heliocentrism, often accessed and realized through experiences of mystical oneness. In psychological heliocentrism our identity, relationships, and world orbit around our identity as Self, one with All. This is not only grandiose, but is commonly accompanied by a strong experience of universal truth, which leads us to believe what we have found to be real and true is real and true for others, or should be. This leads to “spiritual colonization:” attempts to convert others to our worldview instead of at least first attempting to understand the world from their perspective. This lack of empathy can easily be in the service of exploitation. Polycentrism, in contrast, holds self-identification very loosely and arbitrarily, surrendering it easily and shifting to other loci of identity. The result is a much less defending, more open, less brittle and more adaptive interaction with the world as well as both social and intrasocial others, speeding development and opening us to reframings and creative emerging potentials. Polycentrism is not to be confused with polytheism or making separatism into an ontological reality, as dualisms of all varieties do. Instead, polycentrism is an innate expression of holons. Every distinct perspective is a whole that is a part of a greater whole. That is as true in the interior collective quadrant of interobjective “others” as much as it is in the exterior collective quadrant of objective outgroups. Extended identification with multiple perspectives via interviewing them generally leads to a disidentification with the common needs of the body, emotions, mind, and self and into a growing identification with a polycentric identity grounded in mutual respect. This is much more of a humanistic than spiritual orientation, perhaps largely as an artifact of the collective nature of the methodology, which emphasizes collective development and factors that fundamentally support relationships, including respect, reciprocity, trustworthiness, and empathy. Non-state centered/States clearly delineatedWe can easily become fascinated with altered states, such as dreaming and mysticism, and become preoccupied with accessing them. Indeed, they have a great deal to teach us. Intrasocial perspectives, regardless of the state in which they originate, consider this irrelevant, since they remain themselves regardless of the state which produced them. While different states alter our consciousness they don't appear to alter the consciousness of interviewed intrasocial emerging potentials. The result of this awareness, which is itself a product of identification with multiple intrasocial perspectives, is a leveling of states and a reduction in the meaningfulness of various dualities that we depend upon in waking life, such as between waking and dreaming, reality and illusion, objective and subjective. The result is not a slide into a monochrome relativism or indifference but paradoxically, rather a movement toward clarity of meaning and problem-solving based on a specific set of circumstances. The movement from psychological geocentrism toward polycentrism moves us beyond the dualities intrinsic in a self that experiences multiple states. That ties into the next characterological distinction, between our needs or relational exchanges and the simple amplification of embodied presence. Amplification of presence/Relational exchangesWhile we generally associate possession with altered states, as children we internalize the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others continuously, as a foundational aspect of learning. In a real sense, we are “possessed” by the identities of those we encounter. Those identities script us and create a major portion of our identity - the language in which we think, our assumptions about what is real and true. They also script us as to what we need and don't need and what goals to strive for in life. We are largely defined by how much time and energy we spend fulfilling various physical, emotional, interpersonal, cognitive, or transpersonal needs, defined by Wilber as “relational exchanges.” Because interviewed imaginal elements exist largely apart from these defining contingencies, what remains is largely the experience of their presence and the amplification of that presence in our awareness. Sometimes that presence can be very real and powerful, even a theophany or kratophany, but generally it is much more subtle, manifesting as a general reframing of our worldview and experience of this or that dream, mystical experience, or life issue. This is very different from remaining stuck in viewing states and others through the narrow slit of psychological geocentrism, or attempting to escape into enlightenment. Relative freedom from identity defenses due to relative freedom from identity/Ideology, worldview in defense of identity

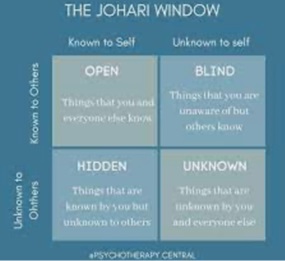

What Ken Wilber has referred to as “The Atman Project” is the defense of identity by building and justifying our worldview and ideology. Polycentrism that deconstructs identity and state-generated dualisms by the evocation of transformative presence in the form of alternative perspectives with which we successively identify generates a relative freedom from our identity defenses because we no longer have to go through life defending ourselves from perceived but false threats to a delusional identity. This allows us to move from an obsessive focus on self-development into greater multi-perspectivalism, both personal and transpersonal/phenomenological. Rather than moving into identity fragmentation or decompensation, waking identity remains objective and intact, only without chronic fears of loss of control. Experiential multi-perspectivalism/Personal developmentOur waking identity centers around personal development, leading to some definition of happiness, fulfillment, integration, or enlightenment as the purpose of life. None of these appear to be primary foci of interviewed emerging potentials, which focus more on simple disclosure of their presence and how it is expressed via their individual worldviews. Personal development is the natural preoccupation of childhood, youth, and those adults focused on their needs and various relational exchanges, including the quest for enlightenment or freedom from samsara. In contrast, collectives are not primarily invested in needs on a personal level but on ways that enhance the development of groups. Intrasocial group members are typically uninterested in personal development as well, but this awareness is normally not only hidden, due to our lack of identification with their perspectives, but is largely irrelevant to our focus on self-development and enlightenment. Like collectives, experiential multi-perspectivalism is focused on group or contextual enhancement rather than personal development. Phenomenologically accessed unrecognized assumptions/Habitual, scripted unrecognized assumptionsOur identities and worldviews are largely comprised of scripted, unexamined assumptions that we not only take for granted but defend against competing, conflicting perspectives. Intrasocial methodologies unearth these unexamined assumptions while disidentification teaches the value of the suspension of scripted, previously unrecognized or prioritized emerging potentials which are brought to light and amplified. The result is a broader reframing of our identity and worldview and a growing disidentification with our scripted identity and the assumptions that support it and which demand defense. An intrasocial worldview is thoroughly phenomenological, meaning it suspends ontological assumptions about the ownership of such perspectives while interviewing multiple perspectives to access a framing that includes but transcends that of the self and Self. The tabling of assumptions is a pre-requisite to disidentification with our sense of self and worldview in order to become or identify with outgroup worldviews. The Johari Window is a useful concept that divides experience into “Known to self and Known to others” (Open), “Known to self but not to others” (Hidden), “Known to others but not to self” (Blind), “Known to neither self nor others” (Unknown). Intrasocial worldviews are only revealed by methodologies like Dream Sociometry that objectively compare and contrast patterns of preference, whether cognitive, emotional, or behavioral. Unless one follows the injunctions and has them validated by peers in the method, we are likely to stay blind and much about ourselves, others, and life is likely to remain hidden and unknown.

Rather than using the map of cognitive, integral/postmodern multi-perspectivalism, intrasocial perspectives use a phenomenologically-based transpersonal, intrasocial, multi-perspectival “walking of the territory” via becoming and interviewing imaginal elements to express and examine worldviews. By doing so we can access perspectives that not only are not known to us but known to others, particularly intrasocial others, thereby reducing blind spots. However, it also discloses those things that are known to us and that we keep hidden from others by demonstrating that these are already fully recognized by intrasocial others. The consequence is that the hidden, private dimension of our lives becomes less important and more transparent. In addition, phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism surfaces relevant information that is unknown both to us and to social others, often experienced as creativity. Finally, it can reveal information that is not only unknown to us and social others but to multiple intrasocial others, thereby reducing the realm of the unknown. Phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism/Prepersonal and cognitive multi-perspectivalism

An intrasocial worldview distinguishes among various varieties of multi-perspectivalism. Prepersonal multi-perspectivalism involves the childhood accretion of identity by identification with the perspectives, roles, feelings, language, and behaviors of others. While this process slows as we solidify our sense of self and switches to the maintenance of our established core identity, it never stops. We either assimilate other perspectives into our identity or ignore or reject them all our lives. This intrinsic form of multi-perspectivalism is prepersonal, meaning that it happens automatically and out of our awareness, as part of the cognitive structure of learning that we were born with. By contrast, personal multi-perspectivalism involves the conscious expansion of identity by taking on the perspectives of other individuals and/or cultures, as adults. This occurs superficially as actors taking on dramatic roles or when we vacation in foreign, exotic countries, but these identifications are generally temporary and superficial, generally having little lasting effect on our identity or worldview. They may feel liberating, but that identification is more like a temporary state access than some stable transformational experience. If we go into another country and maintain our own cultural identity, as many Turks immigrating to Germany have done or as Chinese workers in Africa typically do, personal level multi-perspectivalism is unlikely to occur. Lasting, transformative multi-perspectivalism occurs when we live with families in another culture or take up residence and work in another culture, as long as we do so in a way that involves us in the home lives of locals. What is required is deep immersion and identification that leads to a fundamental broadening of our sense of self and our worldview. In one of a series of essays on these varieties of multi-perspectivalism, I cite the example of Scott Ritter, a committed Marine brought up to hate Russians and who studied Russian history so as to “know his enemy” in order to kill Russians better. Work took him to live in Russia as a monitor/enforcer of US/Russian arms reduction treaties. In the process he came to understand, respect, and appreciate the worldview of Russians, which fundamentally enlarged both his sense of self and his worldview. This is an example of lasting, transformational personal level multi-perspectivalism. The third variety, vision-logic or integral aperspectival multi-perspectivalism, is cognitive rather than experiential. One learns to recognize different worldviews and stages of their development and to organize them into maps and relationships. Integral AQAL and Spiral Dynamics are examples. While this variety of multi-perspectivalism has great heuristic value, generates objectivity, and provides powerful tools for making sense of the world, they specialize in generating cognitive objectivity, that is, the ability to stand back from and dispassionately assess relationships among different levels, styles, stages, states, and quadrants of development, both individual and collective. Objectivity is disidentification, and that is an important first step in any phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism, which combines active disidentification and identification. That brings us to the variety of multi-perspectivalism that reveals the intrasocial domain. Phenomenologically-based experiential multi-perspectivalism (PEM) involves both the cultivation of objectivity via detachment from not only assumptions, expectations, worldviews, and beliefs, but from our identity itself. Most people are not as good as children at doing this, mostly because we make a priority for most of our lives of developing an identity, using it for control and adaptation, and defending it. Therefore adults have a built-in resistance to surrendering identity. Children, on the other hand, having not yet formed a strong sense of self to defend, have much less to disidentify with as a precursor to taking up an entirely different perspective, worldview, and identity. The conscious and intentional identification with other perspectives, regardless of their interior or exterior source or the state of consciousness from which they arise is the second component of PEMs. The duration of such identifications as well as what one does during the identification matters and helps define this or that intrasocial methodology. The one I developed and am familiar with, Dream Sociometry, practices identification using an interviewing, question and answer format in which identifications with multiple perspectives occur over a period of time lasting a half an hour to two hours. Teleological but naturalistic/Naturalistic, but with sensory, emotional, and belief overlaysBy “naturalistic” I mean not fundamentally religious, metaphysical, spiritual, or mythological. Also, explainable by science, falsifiable. By “teleological,” I mean driven by purpose or intention rather than by mindless, automatic processes. These two definitions, on the surface, contradict each other, as science tends to be associated with mechanistic processes and the exclusion of teleology. However, I agree with Integral AQAL that intention is intrinsic to the interior individual (II) quadrant, even in a fundamental causal sense within atoms, although calling it something else like Whitehead's “prehension” may be a better fit. Dreams provide a window into this integration of naturalistic, yet teleological phenomena. However, dreams are easily written off as purely subjective creations. However, just like many interviewed emerging potentials accessed through an intrasocial methodology, both naturalism and purposefulness can exist in ways that are not easily or usefully reduced to self or Self creations. By comparison, waking experience is, on the whole, thoroughly naturalistic in that it is largely explained without appeals to metaphysics. Even psychic phenomena, deja vu, and synchronicities can be reasonably explained in naturalistic terms, even though they exhibit teleological dimensions. We generally associate teleology with consciousness, the metaphysical, or supernatural, such as intelligent design as an explanation for evolution or this or that variety of cosmic consciousness. Worldviews are built on assumptions and expectations, such as deism, theism or growth into subtle, causal, and non-dual realms of consciousness. The type of teleology manifested by intrasocial groups is different. For example, Dream Sociograms depict naturalistic patterns of holons that do not imply any particular belief system, yet still manifest priorities and relationships that can be surprisingly autonomous. Chaotic; approaching randomness; not readily predictable/Predictable patterns more apparentWhile our physical world and waking lives, including our relationships, and daily habits, are based on highly predictable patterns of repetition in our physical, emotional, and relationship worlds, our dreams represent a combination of familiarity and foreignness which can approach absurdity or threat. This always present, latent sense of chaos is fundamental to both creativity and the dissolution of self, which we experience as death. Movement toward discontrol and the dissolution of identity is threatening most of the time, for most people. Therefore, it is understandable that humans have an instinctive approach-avoidance conflict with the world of dreams and the taking of multiple perspectives.

Indefinite, ambiguous identity/Definite, confident, capable identityBecause being in control is fundamental to self-development, ambiguity tends to cause cognitive dissonance and is therefore suppressed. We want the security of clear, black and white information and direction. We tend to ignore our dreams because they are inherently ambiguous and regularly bring up themes that call into question what we have come to assume to be real, true, or rational. The polycentrism innate to an intrasocial worldview is ambiguous because it lacks the certainly provided by one stable, set identity. Recognizing the adaptability of having access to an infinite number of identities is a hard sell when we want or need control and security. Ontological indeterminancy/Reality/delusion sharply delineatedInterviewing imaginal, dream, life issue, and mystically-derived elements and perspectives that exist in the interior collective (IC) quadrant can reveal worldviews that reflect interior, collective priorities which may reorient our personal agenda away from both lower relational exchanges such as pursuing financial security or status or emotions that block development, such as fears of failure, and higher ones, such as seeking self-actualization. Instead, interviewed perspectives generally focus on developing core qualities of confidence, empathy, wisdom, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing, although this is at least partially a consequence of the interviewing methodology. When queried, they often score higher in all of these qualities than we do, with the exception of empathy. Most score lower on empathy due to a degree of indifference to the human predicament. However, this is clearly not due to a lack of empathy, based on the depth of recognition of our intentions and those of others generally expressed. Instead it discloses and teaches a deeper variety of empathy that has very little to do with emotionality. Intrasocial worldviews can radically differ not only from our own but from each other as well as the preferences and worldviews of objective others. This is because, as we have seen, imaginal elements do not have the same needs as humans, such as the need to eat, have shelter, or even survive. They are relatively free of the internalization of scripting that we all experience as intrinsic to normal development. Interior collective perspectives provide subjective sources of objectivity that can be difficult to categorize as self or other, which makes them ontologically indeterminate. The broader reframing of our life issues and our priorities came from within, but it can be alien in authentic and important ways. Some of those perspectives are experienced as radically not-self and demand to be treated as objective others, with a status similar to that we give objective others in the exterior collective (EC) quadrant of our waking experience. Where did such autonomy come from? My best guess is that it is due to a synergistic integration of multiple, previously not accessed or articulated perspectives with our own. Subtly influential/Clearer cause-effect relationshipsWe have seen that waking priorities are generally based on security, safety, control, power, relationships, and status needs. Wilber calls these “relational exchanges” that strengthen our sense of self and its competencies in the world. There are generally clear cause-effect relationships in multiple waking areas. Food, shelter, and weapons address hunger and safety. Money addresses control and power. The development of competencies addresses status as well. Even higher end “transpersonal” relational exchanges involving accessing mystical and other alternate states generally enhance our sense of self, but as “Self,” oneness with all, psychological heliocentrism. Our attention is normally magnetized toward these waking needs, experiences and our waking interpretation of them and the cause-effect relationships that solve problems around the acquisition of these needs. The priorities and influences of these interviewed perspectives are far more subtle. We have seen that emerging potentials have largely divergent priorities from those of waking identity because they have no security, safety or status needs. They have no physical bodies to protect and their sense of self is tenuous at best. They don't need to seek enlightenment, self-development, or altered states of consciousness. They do not need to develop or protect their identities. They emerge or re-emerge into awareness and then fade out or are replaced by other objects of our awareness. Consequently, their priorities are often barely discernible and lack relevance to the vast majority of our daily concerns. Their priorities are generally felt only indirectly, through dreams or creative flashes of insight. Phenomenologically-based varieties of multi-perspectivalism access those core, yet species-wide priorities on a consistent and productive basis. Not easily accessible/ObviousWhile sensory, emotional, and behavioral experience is obvious and stable enough, the intrasocial is neither obvious or easily accessible. Intrasocial embodiment is different in the multiplicity of encounters with different perspectives, duration, control, structured interviewing, and collection of information. Such an approach is not easily accessible because it has no obvious relationship to waking priorities that orbit around the attainment of various relational exchanges and because it requires a methodology that is foreign and not broadly taught in 2023. Fusion of profane, sacred/Sacred/profane, other dualities clearly delineatedWaking experience is largely dependent on an assumption of the reality of all sorts of dualities: self/other, preferences/rejections, truth/falsity, fairness/unfairness, day/night, sacred/profane. Interviewed emerging potentials are largely detached from dualities although they use them in their answers to questions. I used to think that the only way to cultivate non-dual awareness was through meditation. Now I know that identification with multiple perspectives not only also does so, but develops competencies that meditation does not, due to the difference between accessing abstract, or non-conditioned objectivity and accessing mundane and multiple forms of objectivity that are relatively non-invested in the vast majority of dualities. Timelessness/Time orientedHumans engage in cyclical time in the cycles of breathing, day and night, work and relaxation, exercise and recuperation, emotionality and relative peace. We engage with linear time when we focus on goals, deadlines, and expectations. Interviewed emerging potentials, in contrast, take perspectives that are relatively timeless. Experiential autonomy/Ownership, controlWe can always claim ownership of any experience, and to a large extent this is true and therapeutic. The question becomes, at what point does the claim of ownership become grandiose, delusional, and toxic? Most people stop somewhere short of solipsism, but have little awareness of how taking too much responsibility, as in the law of karma, is personally and collectively destructive. Viewing imaginal elements as either “parts,” “self-aspects,” or disowned “others,” is different from an intrasocial worldview, which is thoroughly phenomenological. Those ontological designations are assumptions, and phenomenological approaches surface and “table” assumptions in order to reduce self-generated filters that block and distort encountered perspectives. Intrasocial elements generally view themselves as personifications of some aspect of ourselves. However, if asked, they can also say what aspect of themselves one's waking identity personifies. This is generally a difficult concept because most people are not capable of easily recognizing their dependency and subordination to what is experienced as an imaginal element. Ethical line leads/Cognitive Line Leads, UtilitarianEvery worldview claims to be moral, and everyone uses their worldview to claim moral legitimacy and to both deny and justify both their own personal amorality, immorality and personal responsibility for crimes against humanity their society may commit. Immorality is here defined in terms of the external collective quadrant - what others, with whom we are in relationship, view as disrespectful, non-reciprocal, untrustworthy, or non-empathetic actions that are “third degree.” First degree infractions may hurt our feelings or be taken as personal insult; second degree immorality causes major life dislocations; third degree abuses put people in hospitals, morgues, or prisons. The first two can easily be rationalized away as stupidity, zealotry, or ignorance; the third variety is the major reason why there are laws, courts, and prisons. Amorality may be a simple lack of morality, as exists in the animal kingdom. In addition, it can be self- serving thoughtlessness, as we choose to ignore injustices done in our name, or it can be calculated, as implementing policies that discriminate or disenfranchise others in ways that we would not want reciprocated. Animal amorality is abuse or violence done where there is no moral actor, that is, someone or something that knows better. Thoughtless amorality is abuse or violence done by those who know better but who forget or are negligent, like leaving the gas on and blowing up the house or texting while driving and hitting a pedestrian. Calculated amorality is abuse or violence due to “policy,” preferential laws, willful ignoring and avoiding of the plight of others. While in a waking, psychologically geocentric context and in its subset, the heliocentric realm (in which an infinitely expanded Self experiences itself as one with all of reality and therefore the center of it), the cognitive line leads. This is because the cultivation of objectivity is central to developing the ability to stand back and watch first our body, then our emotions, thoughts, intentions, and identity go by. In contrast, in the experiential and phenomenologically-based intrasocial realm of interviewed perspectives, the moral line leads. While the cognitive line leads in self development, the moral line leads in relationships, both social and intrasocial. When we relate to each other the degree of objectivity the other possesses is secondary to whether foundational moral qualities of respect, reciprocity, trustworthiness, and empathy are present. It is not that objectivity is not important, but that we are more likely to dismiss, discount, or disregard it if it comes from a source we don't respect or trust. For example, respect is not required in order to cultivate objectivity, but it is fundamental to both the social-exterior and intrasocial-interior interpersonal and moral/ethical realm. Respect has very little to do with the cultivation of abstract objectivity via meditation but it has everything to do with relationships, whether interpersonal in the exterior collective quadrant or “interimaginal” in the interior collective quadrant. When we take up an intrasocial worldview, we lay down our sense of self through an act of disidentification, and allow ourselves to be possessed and defined by multiple different loci of identity. This is fundamentally an act of respecting that we are laying aside not only our assumptions but our identity in order to listen in a deep and multi-perspectival way. The cognitive line also leads in self-development because the central issues for our waking identity are maintaining and extending control and getting our needs met. The cognitive line is all about the utilitarian business of problem solving to meet these ends. The moral line leads in collective development because the central issue is establishing rewarding interpersonal relationships, not control or fulfilling needs, although those are significant secondary benefits. While establishing successful, meaningful, or rewarding interpersonal relationships may be a means to those ends, they exist as goods independent of self-development. This is a principle that can be observed throughout the animal kingdom. Intrasocial methodologies disclose and create both an understanding of and willingness to behave morally toward both objective and intrasocial others. Rather than using cognition as the foundation for arriving at worldviews, an intrasocial approach uses morality. We can access the intrasocial pre-rationally, say as children, rationally, or thirdly, transrationally, say in mystical experiences, because morality includes and transcends all three realms. The fundamental questions asked by morality, whether by waking, objective, “human” actors, or by subjective, imaginal actors evoked from altered states, are the same. These questions are at least four: “Is there respect?” “Is there reciprocity?” “Is there trustworthiness?” “Is there empathy?” While these questions can be viewed as intrinsic to the interior collective quadrant of axiology as deontological injunctions, they exist in equal importance in each of the other three quadrants. In the exterior collective (EC) quadrant, morality is based on how we answer these questions in relationship to one another, with particular consideration of outgroups, since they represent ignored, repressed, or discounted aspects of ourselves. In the exterior individual (EI) quadrant, morality is (at least) based on our behavior regarding these four conditions. In the interior individual (II) quadrant morality reflects to what degree our consciousness, thinking, and feeling reflects these qualities. Morality and ethics are how universal characteristics of reality show up in the collective domains of values and interpersonal relationships.[2] Prepersonally, on the level of material relationships, respect shows up as the requirement that substances adapt to the properties and structures inherent in other structures. For example, oxygen and hydrogen have unique atomic and chemical structures. These can interact and create a new synthesis, water, but only because hydrogen must interact in certain ways with oxygen and vice versa. There are intrinsic structures and boundaries that must be respected for reactions to occur. The interaction of hydrogen and oxygen is also an example of what we call reciprocity, but on a fundamental, pre-rational, pre-conscious level of reality. The fact that the relationships between oxygen and hydrogen are highly predictable is what we call “trustworthiness” in human relationships. Each element has to identify, or merge with the other to relate to it, which is a precursor of what we know as empathy. We find reciprocal relationships that exhibit the precursors of respect, trust, and empathy throughout the plant and animal kingdoms, but those precursors do not rise to the level of morality. Still, they indicate that the underlying principles are not simply artifacts of human culture but something fundamental to nature. Similarly, on transpersonal and non-dual levels we never outgrow these four definitions of what it means to be moral. If you are a non-dual mystic or an adherent of the Madhyamika four-fold negation, you are wise to deal with other people based (at least) on these four conditions, because other people will assess you based on these criteria, like it or not, fair or not. So, for instance, if you are an adherent of the Hindu/Buddhist doctrine of epistemological dualism, conditioned and absolute reality, and justify your acts in terms of access to absolute reality because of your mystical experiences and degree of enlightenment, those who are disadvantaged because of your choices in the realm of relationship won't care. They will simply view you as disrespectful, or non-reciprocating, untrustworthy, or un empathetic. Who is correct? In the interior individual quadrant, you are correct while in the exterior collective quadrant, which represents social reality, they are correct. If you don't care if you are ostracized, condemned to prison or death, you can discard the judgments of outgroups. If you do, and if you agree with Wilber that the moral line must tetra-mesh for you to evolve level to level in your overall development, then the determinations of others matter. Similarly, your relationship with transpersonal realities, however you conceive of them, will also be predicated on those four conditions. You will respect that which is sacred and assume it reciprocates and respects you; you will assume it is trustworthy and strive to be worthy of its trust; you will experience it as profoundly empathetic, knowing you better than you know yourself, and your sense of oneness with it will be experienced as a reciprocating empathy. This will validate your identification with absolute truth in the interior quadrants and lead you to discount or disown the conclusions of outgroups in the exterior and interior collective quadrants. Respect, if only of structures and boundaries, is fundamental for all relationships. Disidentification, laying aside our assumptions in a phenomenologically-based way, and allowing a perspective to speak for itself, is a demonstration of respect. We can even make our assumption of respect (as well as that of reciprocity, trustworthiness, and empathy) conditional, rather than a pre-existing axiom or assumption, in order to test its validity through the interviewing and life application processes. Respect is also reciprocal, in that doing so is what we want and what we expect others to demonstrate toward us. We want others to lay aside their biases and expectations and to hear and see us for who we are. The tabling of assumptions, a process fundamental to any phenomenological approach, is also an act of profound empathy, because we are not simply assuming we know how the other feels or what they think. Instead, we are asking them and listening in a deep and integral way, to their reality, regardless of how it relates to our own. Trustworthiness is not universal. No one and nothing is universally trustworthy. What matters in most relationships is trust in one or two areas that are critical to a particular context, such as commerce or love. If those areas of trust exist, less trustworthiness in multiple other areas is tolerated. For example, you may be trustworthy as a great cook but not a reliable cleaner or organizer. That may not matter in relationships where there is a sense of equivalence and trade-off in responsibilities. Trustworthiness is also a descriptor of the suspension of fear and doubt, essential for the development and expression of creativity. And because fear undermines both individual and collective development in multiple ways, if we want to evolve more effective worldviews we need to cultivate not blind, but realistic trust. These are important factors that cause the moral line, not the rational line, to lead in understanding both the intrasocial worldview and also in any potential synthesis of worldviews that contains the intrasocial worldview. Transcendent/ImmanentThe majority of feedback we receive from interviewing these imaginal perspectives is personal, because that's where most of us are stuck and direct our attention. We mostly dream about personal events, themes, emotions, and dramas. Although the reframings of our daily life issues provided by interviewing multiple imaginal elements are generally liberating, it is easy to write these perspectives off as the product of immanent “self-aspects.” We easily think, “I already knew that!” Or, “I just accessed my unconscious shadow.” While these interviewed perspectives are certainly self-aspects, sub-personalities, and “parts,” as recognized by shadow work, gestalt, and mainstream psychology, they can also exhibit shamanic, katrophanous, and objective characteristics that demonstrate a degree of autonomy that is demonstrably not ego, self, unconscious, personal unconscious, collective unconscious, archetypal, or Self. Examples include visitations by departed relatives, totem animals, Greek muses, near death and mystical experiences. While such experiences are dramatic, they are outliers. Every interviewed element demonstrates some degree of autonomy, but because that degree is generally small, it is easy to discount, ignore, or minimize what that autonomy implies. All fall into the category of distinctive “otherness,” yet exist as interior others with which we are in relationship. To force them into subjective categories as “self-aspects” or even collective archetypes, is a Procrustean discount of their autonomy, just as declaring them to be objectively real, as say, shamanic totem figures or possessing spirits, disowns our own responsibility in their existence. Instead, interviewed imaginal elements accessed in the interior collective quadrant exist interdependently, partially objective and partially subjective, partially “other” and partially self. Think of them as existing on a continuum between otherness and self, with every intrasocial perspective falling somewhere on that line, but none being wholly “other” and none being wholly self. The transcendent nature of these perspectives is subtle and may take a while to recognize, but the breadth and inclusiveness of reframings is an indicator that we are accessing perspectives that not only include and transcend our own, but which have their own agendas, which can be quite at variance to our own. The utility of the reframings of important life issues is generally impressive and unexpected enough to keep the curious or creatively motivated individual coming back to experience and learn more. Meditation creates impersonal objectivity, not identification with multiple perspectives. Mystical experiences generally generate psychological heliocentrism and deep humility at best, or grandiose self-inflation at worst, as a consequence of the very real experience of oneness with everything and everyone. Occult, psychic, shamanic, and spiritualistic experiences can create a sense of the reality of supernatural “others” which exist in other dimensions and which act independently of our preferences. These can possess us as daemons, spirits, gods, or collective archetypes and take us to places and experiences that can be heaven or hell. In either case these “others” are not experienced as co-created, or as at least only partially under our control. Also, these encounters are generally singular: we become this or that “other” and draw conclusions about reality from that experience. Tibetan Deity yoga provides examples. Because accessing the intrasocial worldview accesses perspectives enmeshed in our life issues, the objectivity they provide is much more of a concrete, problem solving variety. A component of a larger worldview/Multiple worldviewsIntegral Deep Listening, of which accessing a polycentric, intrasocial worldview is one sub-discipline, has ten components that synergistically support three aspects of awakening: healing, balancing, and transformation. The first three support awakening via emphasizing healing. The next three support awakening via emphasizing balancing. The last four support awakening via emphasizing transformation. Script analysis is the process of learning how you have been scripted by your genetic inheritance, family, culture, and society, sorting through that scripting to keep those elements that support awakening, and then to align those priorities with those of your emerging potentials and life compass. Escaping the Drama Triangle in the three dimensions of relationship, thinking, and dreaming involves waking up out of processes that block intimacy and authenticity by generating persecution, powerlessness, and addiction. Eliminating cognitive distortions, including emotional distortions, cognitive biases, and logical fallacies involves waking up out of emotional reactivity and learning how to reason, both essential forms of objectivity. Goal setting supports awakening by generating life meaning and defending against depression, anxiety, drama, and addiction. Assertiveness supports awakening by generating authentic confidence, a core life quality necessary for life balance and transformation. Triangulation supports awakening by providing superior problem solving by supplementing authoritative input and common sense with the perspectives of interviewed intrasocial emerging potentials. Interviewing of emerging potentials, whether dream or waking life elements, wakes us up out of various dualisms and into polycentrism. Pranayama uses seven octaves of breathing to wake up. Meditation supports awakening by cultivating pure objectivity. Generating a Statement of Intent supports awakening by remembering and integrating all these elements.[3] The overall purpose of Integral Deep Listening is to find and deepen balance, harmony, and inner peace as a foundation for both healing and transformation. In order to do so we need not only to access higher forms of integration, which is what meditation, pranayama, and interviewing do, but identify and neutralize blocks to inner peace, in the form of scripting, cognitive distortions and biases, drama, and lack of assertivenesss. So IDL addresses and teaches all of these tools. Broader multi-perspectival problem-solving/Narrower multi-perspectival problem-solvingWe typically use multi-perspectival approaches to problem-solving. Most of our decisions are based on a combination of what we think, feel, or know, including our intuition or conscience and on what some external authority tells us, whether parent, teacher, Google, AI, or guru. We consult different authorities, like Google or Chat GPS, in addition to our common sense, in decision-making. Intrasocial worldviews take a broader, multi-perspectival approach to problem-solving called “triangulation.” Outgroups are both social, like the Chinese worldview, and intrasocial, like a dream monster. We don't normally identify with either of them because they are outgroups, the “other,” by definition. When we consult both social and intrasocial outgroups and compare their perspectives with our own and expert input, the result is triangulation, which provides superior decision-making than simply accessing one or two of these three sources of knowledge. However, very few take up an injunctive methodology of interviewing social and intrasocial outgroups. The result is that the input of perspectives that know us at least as well as we know ourselves, since they are aspects of ourselves, unlike objective authorities, and that are free of the agendas, scripting, and biases that filter both the input of our ingroups and our own preferences, is generally lacking. Conscious embodiment/Unconscious possessionIn the interior individual quadrant, we take up and personify thoughts, feelings, and consciousness that is associated with our identity. That is almost always a matter of seeing things, even in altered states, from the perspective of our waking identity and its worldview, even if vastly expanded in a mystical experience. Experience is still filtered through our waking identity and worldview in a type of unconscious possession, in that our perception is largely predetermined by socio-cultural scripting and cognitive biases in which we are subjectively immersed and that we are largely unaware of. For the interior collective holon we take up and become other identities besides our own. For the exterior individual quadrant we act out our identity and its intentions in the interior individual quadrant. Intrasocially, for the exterior quadrants, we take up and act out relationships and group identities. This involves enacting the recommendations made by interviewed perspectives, ideally while identifying with their embodied identity. For example, if the answer to procrastination is supplied by a crocodile, which lays silently and passively until a duck happens closely by, then the injunction, when one wants to stop procrastinating, is to take on the beingness and behavior of the crocodile and its relationship to “ducks,” that is, to things that one wants/needs to accomplish. That is, to attack them, get them done, and return to a state of placidity. Of course that is only one example of countless possible and equally applicable metaphorical framings. Empirically accessible/testable/Empirically accessible/testableRecommendations made by interviewed imaginal elements as well as intrasocial methodologies themselves are not simply a theoretical formulation of the interior collective quadrant. They are empirically testable in the exterior quadrants. To do so one 1) learns the injunctions of the methodology,[4] 2) follows them (performs the experiment themselves), and then 3) validates them against the results of others skilled in the methodology. This is the same process used for verification in any physical, cognitive, or transpersonal domain, as described by Wilber in The Marriage of Sense and Soul and other works.[5] This method is further (and critically) tested by the operationalizing of recommendations made by interviewed perspectives. When applied in one's daily life is there healing, balancing, and transformation or disintegration, chaos, and devolution? Or is there no change?

IDL does not claim to be the only methodology that discloses an intrasocial worldview. Instead, it is an example of one possible methodology and approach to it. Other approaches can be developed which will do so as well, as long as they contain the following elements:

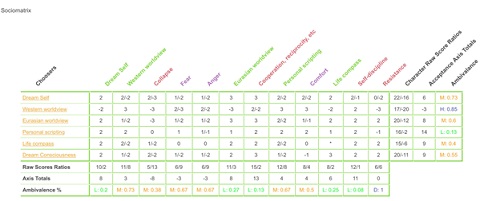

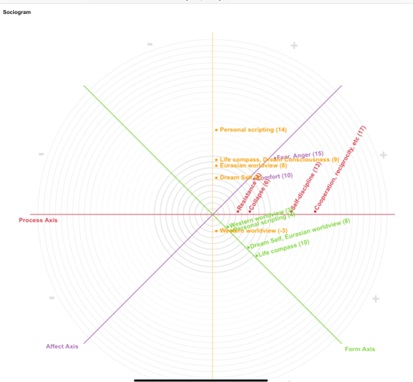

Interviewing is the seventh of the ten elements of IDL listed above. It has two forms, individual and multiple element interviewing. The second of these, called Dream Sociometry, teaches waking up via moving from psychological geocentrism to polycentrism and is phenomenologically multi-perspectival. It has four major components: 1) The creation of a Sociomatrix, 2) the collection and compilation of character elaborations of their preferences in response to questions in the Dream Sociometric Interviewing Protocol, 3) the creation of a Dream Sociogram, which views the dream, mystical, or life situation from the worldview of the collective as a whole, and 4) the operationalization and application of recommendations made by interviewed elements. Intrasocial perspectives are accessed by a process similar to elenchus, or Socratic questioning.[6] The interviewing protocol, an aspect of Integral Deep Listening, asks questions designed to first assist one in becoming the interviewed character or element, then accessing what aspect of ourselves they most closely represent, then providing it with an opportunity to explore its transformative potentials, then scoring itself in terms of core qualities associated with healing, balancing, and transformation. The character is then given the opportunity to say how it would live our life if it were in charge and how it would deal with life issues that are of personal concern to us. At the close of the interviewing protocol, subjects are asked if they want to implement any of the life changes recommended by the interviewed perspective. If they do, the recommendations are operationalized and an accountability structure is created so that the credibility of the methodology can be tested and validated personally. Here is an example of a Dream Sociomatrix and a Dream Sociogram. Examples of the interviewing protocol and application recommendations can be found at IntegralDeepListening.Com under “Questionnaires,” “Dream Sociometry.”

The choosers are in yellow at the left, including “Dream Self,” (the dreamer) and “dream consciousness,”(the overall, all perspective encompassing perspective). The chosen characters (in green), actions (in red), and emotions (in purple) are written across the top, creating a matrix of choosing characters and chosen elements. The numbers above are degrees of preference: 1 = like, 2 = like a lot, 3 = love, -1 = dislike, -2 = dislike a lot, -3 = hate. A blank indicates “no preference.” A “split” score represents ambivalence, liking and disliking at the same time, with degree of liking always written first. The totals at the right indicate summed degrees of chooser preference/rejection; the totals at the bottom indicate summed degrees of chosen element preferences. Of course, any situation can be assessed in this format, including historical events, fiction, mythological, waking life crises, dramas, or choices, and mystical experiences. The advantage is that it accesses and demonstrates multi-perspectivalism within any context. You can look at the above matrix and assess how similar or different the preferences of various choosers are from you (Dream Self) and each other. You also learn how preferred or rejected various choosers, actions, and emotions in the context are by this or that choosing perspective. Interviewing multiple perspectives at the same time, whether they share a dream, a waking life, mystical, or historical context, generates a framing that includes but transcends that of identity in the interior individual quadrant or in any of the four holonic quadrants subordinate, within the (II) quadrant. Just as sub-units in a mathematical set are included by and are subsumed by the perspective of the set to which they belong, so the perspective created by the combination of various elements from any life situation derived from waking, dream, or altered state, transcends that of our own perspective in the interior individual, whether conceptualized as ego, self, or Self. The result is that you have undeniable evidence not only of multi-perspectivalism, but of relative autonomy. Because these various non-self perspectives are normally hidden not only from others but from yourself, they are constitute invisible influences on your mood, decision-making, and creativity. That influence could be positive and under-utilized, because it is unrecognized, or it could be negative and unnecessarily toxic, because it remains unrecognized when it could be surfaced and dealt with. A further advantage of gathering all this data is that it can then be depicted in a sociogram:

Here we see the choosers (in yellow) depicted on the vertical “acceptance” axis, the chosen characters depicted on the green “form” axis, the chosen actions on the red “process” axis, and the chosen emotions on the purple “affect” axis. What you are viewing is the subject, that is, yourself, if you create a Dream Sociomatrix, presented in the context of the patterns of group preference. Are you looking at “Its” in the exterior collective (EC) quadrant, “Is,” in the interior individual (II) quadrant, or “Wes” in the interior collective quadrant? Since yourself, Dream Self, is merely one of several choosers and chosen elements, even difficult to pick out, you are simply one more “It,” or “other.” Since all of these elements can be considered self-aspects, they are all “Is.” Since they all form a collective that is interior and undisclosed until their preferences are collected and explained, they are all “Wes” in the interior collective quadrant. These groups form predictable patterns of preference that can differentiated along dialectical lines, and I have done so elsewhere.[7] BenefitsWhen we take any element, whether from our waking life or some altered state of consciousness, and become it, we enter the intrasocial reality of our interior collective holonic quadrant. There are many reasons why doing so is not only smart, but wise. First, intrasocial perspectives are relatively autonomous, meaning that they often have preferences and worldviews that are at some variance from our own. This often takes people by surprise, as they assume that interior perspectives are going to reflect their preferences and worldview. We can access information that is known to others but not known to ourselves, information that is not known to either others or ourselves, and information that we know but is hidden or secret. Second, these different perspectives are largely independent of both our worldview and those of outgroups in our exterior collective quadrant. That means that they are not scripted like we are, nor are they scripted like proponents of alternative worldviews are. The result is a degree of objectivity not only from our own subjectivity but from multiple prevailing zeitgeists. These therefore serve as subjective sources of objectivity. Third, because these perspectives are imaginary, they are neither alive nor dead, time limited, and free of the constraints of space. They do not need to eat, drink, seek security, power, or status and are therefore much more likely to be relatively free of both drama and addiction. Fourth, they don't need to sell us anything, manipulate us, or generate our support for their agenda, as others in our lives may wish to do. This is not to claim that intrasocial perspectives do not have agendas or do not want us to hear, respect, and act on them. They do. However, if we don't, it will not affect their reality in ways that are existential for them. Fifth, intrasocial perspectives are “emerging potentials.” That means that they personify unborn, unrecognized possibilities that are being born into awareness, with a greater or lesser possibility of becoming priorities in our lives. Sixth, rather than providing new information or revelations, interviewed emerging potentials typically do something much more important. They reframe our perspectives and restructure our life priorities in ways that heal, balance, and transform. Seventh, intrasocial perspectives point us toward our unique life compass, an evolving center of stability that integrates and balances both individual and collective aspects of holons. Eighth, the resulting input changes, adapts, and evolves as we do. The result is not a static worldview, mood, or identity, but one that transforms based on changing circumstances and needs. Conclusion: The relationship of the intrasocial to other worldviewsWhen the priorities of multiple interviewed emerging potentials of multiple people are taken together, they form patterns of priorities that are theorized to represent those of a hypothetical collective life compass. Therefore, both individual and collective worldviews that are relatively independent of personal and collective societal worldviews can be accessed and then compared to other worldviews, such as the Western, Global South, Chinese, Russian, and Artificial Intelligence worldviews surveyed in this series. When this is done, what is found?

NOTES

|