|

TRANSLATE THIS ARTICLE

Integral World: Exploring Theories of Everything

An independent forum for a critical discussion of the integral philosophy of Ken Wilber

Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). Frank Visser, graduated as a psychologist of culture and religion, founded IntegralWorld in 1997. He worked as production manager for various publishing houses and as service manager for various internet companies and lives in Amsterdam. Books: Ken Wilber: Thought as Passion (SUNY, 2003), and The Corona Conspiracy: Combatting Disinformation about the Coronavirus (Kindle, 2020). TABLE OF CONTENTS | REVIEWS

To Test or Not to Test, That's the QuestionThe Corona Conspiracy, Part 13Frank VisserWe have a simple message for all countries: test, test, test. Test every suspected case. If they test positive, isolate them and find out who they have been in close contact with up to 2 days before they developed symptoms, and test those people too [if they have symptoms].

A lot of misinformation is doing the rounds these days about the need for and usefulness of testing for the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

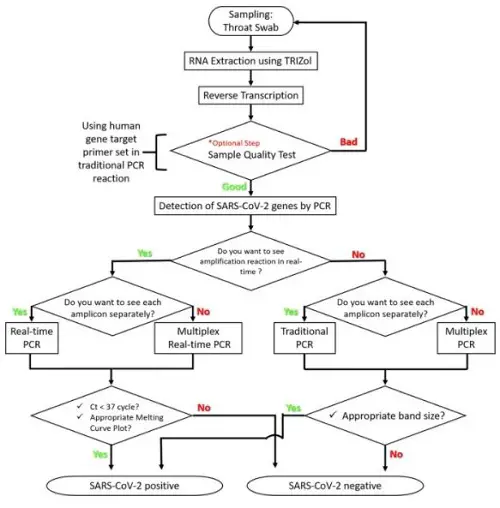

A lot of misinformation is doing the rounds these days about the need for and usefulness of testing for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Some virus denialists claim that the tests currently in use are "scientifically meaningless".[1] Others claim that the tests produce false positives, up to 80%[2], because they actually test for general genetic material the human body has in its cells. Some claim that by testing at such a frequent level as we do today, we have created a veritable "casedemic": a steep increase in the number of cases of COVID-19, without the expected increase in deaths or even hospitalizations, feeding the suspicion that these case numbers are highly inflated.[3] Many claim that the inventor of the PCR test, Nobel Prize winner Kary Mullis, claimed the test should not be used for the detection of viruses. Some caution against the current testing craze because a full clinical diagnosis requires much more than a simple test result.[4] And Donald Trump famously suggested casually to test less, following the logic that "by having more tests, we have more cases, and that makes us look bad."[5] SOME TECHNICAL CLARIFICATIONSSo what to make of all this? Can we get some clarity about what these tests can, and cannot, do for us? Are they "scientifically meaningless", or are they useful—within limitations? And what do false positives and false negatives (and their opposites true positives and true negatives) actually mean? Let's start with the terminology.[6] The tests used for detecting SARS-CoV-2 is called "RT PCR test", which confusingly can stand for "Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction" or "Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction", otherwise known as "qPCR" or "quantitative PCR" (do check out the Wikipedia pages for the technical details). What is important is that this is not just a qualitative Yes/No test, but a quantitative test: it can measure the viral load a person has, which is of course highly relevant, because you want to single out those persons that have the ability to infect others. What the PCR test basically does is multiply a specific short genetic sequence of a virus (which has been fully sequenced) in a sample so it can be detected (or not). See Part 1 for a fuller explanation of what PCR does). Here's a nice diagram that shows what the options are in the domain of PCR testing:

Selection flowchart for SARS-CoV-2 detection protocols (Nature).[7]

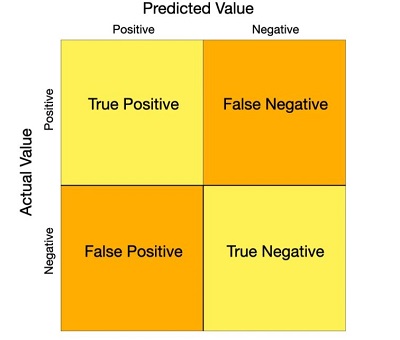

Now as to the positive and negative results of a test. In its most simplified form, we would expect a sick person (i.e. with symptoms) to get a positive test result, and a healthy person (i.e. with no symptoms) to get a negative test result, when he is tested for COVID-19. If a healthy person gets a positive result, this is called a "false positive". And conversely, if a sick person gets a negative result, this is called a "false negative". We want to avoid both errors of course. Especially with viral diseases it can get complicated pretty soon, with its a-symptomatic (you have the virus but no symptoms at all), pre-symptomatic (you have the virus and will develop symptoms soon) and post-symptomatic (you have recovered, but still carry some viral load) cases. In those cases the test would correctly spot the virus, but the positive result would falsely be mistaken for a false positive, given that there are no symptoms.

A confusion or error matrix of possible test outcomes (thehill.com)

And to make things even more complicated and maddening—but relevant for our series—virus denialists such as Engelbrecht, Lanka, Kaufman and Icke are in a peculiar predicament. If the existence of viruses is flatly denied, no true positive test result would be possible at all, since in their contorted minds there is nothing to test for! All or most results would be interpreted as "false" positives. But even that would be meaningless for what would a "true" positive mean for them? Alternatively, if the tests test for general genetic material, we would expect a very high number of true positives—and that would be a correct result. So "false positive" means different things to those who believe viruses exist and those who deny their very existence. In the first case the number of false positives is usually very low (less then 10%), in the latter it is claimed to be very high (about 80%). Are you still there? "So why didn't they purify the virus?"To prove I am not making all this up, I will quote directly from Andrew Kaufman, who is Icke's main source when it comes to virology (or should we say no-virology?), where he describes how the virus was discovered, how the relevant test was produced and how (un)reliable that test actually is (in his understanding, which leaves much to be desired): They did take some other body fluids, they did take blood they took oral swabs and nasal swabs, but it is in the lung fluid where they really found what they or think they found what they were looking for so when they took this lung fluid out they did not first try to find a virus in there and separate it out and purify it but the first thing they did was find and separate some kind of genetic material. Quite an interesting strategy. And what they found was some RNA.  Andrew Kaufman: ‘I think I know what is really going on.’ So one example of a type of error that I think we'd be very concerned about with this test (because we don't want to be mislabeled as being positive for this alleged virus and then risk being quarantined or perhaps even detained), so we want to know the accuracy. It is a hell of a job to disentangle the information from the disinformation in this quote, so let's first start with the scientific story.[6] If a test isn't "sensitive" enough you get false negatives: you have the virus but it is not detected. When a test is not "specific" enough you get a false positive: it finds a virus similar to SARS-CoV-2, but not the real one. So tests can vary in sensitivity and in specificity, depending on the purpose they are used for. Tests for SARS-CoV-2 are highly specific, because they are looking for a genetic sequence that is typical for this particular virus. Sensitivity can also vary, but what is more relevant: during the test the genetic sequence that is looked for is "amplified" or doubled in successive cycles, so the quantity of the material is high enough to be detected (with the help of fluorescence). But even running an infinite number of cycles will not produce a positive result if the genetic material wasn't present in the sample in the first place. As you can see, even though the test results are often presented as a simple positive or negative outcome, it is possible to measure the viral load in a sample. If it takes relatively few cycles to amplify the genetic material to perceptable levels, the viral load was high. Alternatively, if it is detected after a very high number of cycles, the viral load was low. This is called the Ct value or threshold value above which the RNA can be detected. A high Ct value corresonds to a low viral load. Now let's see how Kaufman clashes with the conventional scientific understanding:

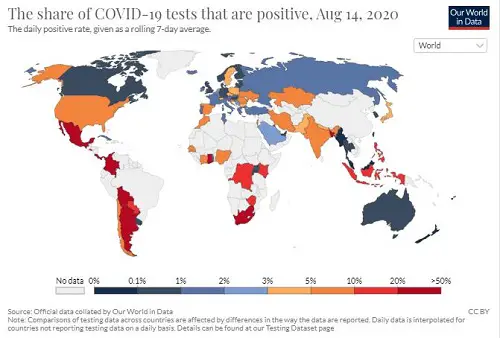

Leaving behind us the amateuristic mess Andrew Kaufman has created for himself when it comes to virology in general and SARS-CoV-2 in particular, other concerns have been raised related to this PCR test that merit some further attention. Other Concerns about the PCR Test Kary Mullis Is it really true that Kary Mullis, the inventor of the PCR technology, claimed this test is not to be used for diagnostic purposes, but is only meant as a means to manufacture large quantities of a given material? But in that case, why is it called a "test" in the first place? Read carefully what the original patent (there are several of them) of this invention says about this: System for automated performance of the polymerase chain reaction (US Patent US5656493A) That conclusively proves that the whole point here of amplifying or manufacturing a given genetic material is to be able to detect it in a test for the presence of a disease. The patent continues: "Such test might be prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell anemia,... Another test is the diagnosis of the AIDS virus, which is thought to alter the nucleic acid sequence of its victims." Later in life, Mullis became an AIDS denialist, arguing that it was not caused by HIV, a climate change denialist and a believer in astrology—but that's another story. If you think all this doesn't apply to viruses, read this in another patent by Mullis: Various infectious diseases can be diagnosed by the presence in clinical samples of specific DNA sequences characteristic of the causative microorganism. These include bacteria, such as Salmonella, Chlamydia, Neis seria., viruses, such as the hepatitis viruses, and parasites, such as the Plasmodium responsible for malaria. (Patent number: 4,965,188) Then there are some who claim that the PCR test in itself doesn't provide a complete clinical diagnosis, and that's correct. But that was never its intention. It does however provide a simple metric which can support a health department policy in a given country. Is the number of cases going up or down? How does it compare to other countries? Should we test only very sick people who are already hospitalized, or also those who have symptoms and suspect they have COVID-19? Or anybody in a country (if that would even be practically feasible)? As you will understand, there are practical problems to this, and it is always better to test more than less, I would say. But then, does this not create a "casedemic" with inflated numbers, thus overestimating the severity of the pandemic? Given the high sensitivity of the COVID-19 PCR tests, this would seem to be a reasonable concern. If even the tiniest amount of viral RNA can be detected, should we put such a person in quarantine and label him or her as "infected" and capable of infecting others? Or should we conduct further clinical tests before we use such a label? It is all a matter of gradation, I think, and I would suspect that the viral load of a person is an important variable here. But I am not sure if the COVID-19 etiology allows for a gradation of severity (so for example you could be a "grade 3 SARS-CoV-2 infected" or a "potentially infective person". But if even a person without symptoms can infect others, it is—as always in life—best to err on the side of caution here. It is sometimes suggested that the PCR test might also catch fragments of a dead virus, once a person has recovered from the disease. That might be true, but that can easily be covered by testing recovered persons as a separate group. And does even Donald Trump have a point that the more you test, the more cases you will find? In a sense, that's a no-brainer, except for countries that have get rid of the virus. This makes a comparison between countries that test widely and one that barely test rather difficult. Any cross-country comparison during this pandemic is full of complications if procedures are not standardized. But the absolute numbers don't count here, it is relative numbers that matter. How many tests should be performed to find one positive case? If that number is low, the frequency of infected persons might be very high in a given country. Or alternatively, only very sick persons are tested. And conversely, if it takes a lot of tests to find such a case, the number of infected persons is very low indeed. The WHO advises to keep the percentage of positive tests at 5%, see the world map at the bottom of this essay.[9] Also, changes over time matter: if in a given country the percentage of positive tests rises, this is a strong indication that more and more people get infected and the pandemic spreads. Other questions arise. How many hospitalized cases die? And how many deaths does a country count per inhabitant? If a country has a low number of hospital deaths, this might be due to good (and expensive!) healthcare—at least for the rich who can afford to go to a hospital at all. If there are many deaths per capita in a country, this might be a bad omen for how it deals with the pandemic. This is subtlety Donald Trump is still struggling to understand, as this hilarious video fragment shows:

"Look, we're last, meaning we're first! And we have cases, because we are testing!"

The Relative Value of TestingSo what can we conclude about the PCR test in the context of COVID-19? It is a highly specific and useful test, even if it doesn't provide a complete clinical diagnosis. The percentage of positive tests is quite low, as we would expect, but it depends on the group that is tested (healthy, moderately or severely ill). It is most definitely not "scientifically meaningless", unless perhaps when you are a virus denialist, and you can't make sense of the test outcomes, given that there is no virus in the first place. The casedemic skeptics claim that the higher number of cases we experience today, is completely due to the higher number of tests done. But because the number of deaths is everywhere low, they say, this proves we are looking at an artifact. Yet, this has been criticized by others pointing to the fact that in the first months of the pandemic large numbers of old to very old people died and no lockdown measures were in place, whereas at the moment we see that younger people are now infected as well, and lockdown measures are fully in place almost everywhere. Both factors could explain the low amounts of deaths: lockdown measures are effective and younger people are less likely to die of COVID-19 (though there are many exceptions to this, as we all can read in the newspapers). Also, we have learned the hard way how COVID-19 patients can be treated at an earlier stage, leading to less deaths. But even then younger people and even very young children might still be able to infect the elderly, so we would expect to see a rise in deaths as well if the lockdown measures are relaxed. However, it is good to realize that these casedemic skeptics don't deny the virus, or the pandemic, as it raged in early 2020; they just claim the pandemic is now over and by exclusively concentrating on "cases" we sustain the illusion that the pandemic is still growing. I don't know what's wisdom here, and have always felt that in the end this is a case of finding the right balance between underestimation and overestimation of the severity of the pandemic, between the reckless and the cautious mind (see Part 8). Finding such balance is best reached by using all the good science we can get, and least of all by get getting side-tracked by virus denialists and paranoid scientists. NOTES[1] Torsten Engelbrecht & Konstantin Demeter, "COVID19 PCR Tests are Scientifically Meaningless", off-guardian.org, Jun 27, 2020. Please note: "Overall, we rate OffGuardian a Strong Conspiracy and Moderate Pseudoscience website that also promotes Russian propaganda." (mediabiasfactcheck.com). Full blown virus denialism can be found in the earlier book: Torsten Engelbrecht & Claus Koehnlein,Virus Mania: How the Medical Industry Continually Invents Epidemics, Making Billion-Dollar Profits at Our Expense, Trafford Publishing, 2007. For a fact check see: "COVID19 PCR tests are scientifically meaningless", www.politifact.com, July 7 2020. From which:

See also: Ian M Mackay, PhD (EIC), "Yes, PCR tests can detect 'the COVID virus'", virologydownunder.com, August 4, 2020. [2] Andrew Kaufman, "SPECIAL REPORT: Humanity is NOT a virus!", YouTube, 1 Apr 2020. [3] Ivor Cummins, "Crucial Viewing - to truly understand our current Viral Issue #Casedemic", YouTube, 12 Aug 2020. [4] Richard M. Fleming, "Moratorium on PCR testing", YouTube, 2 Aug 2020. [5] Maegan Vazquez, "Trump now says he wasn't kidding when he told officials to slow down coronavirus testing, contradicting staff", CNN, June 23, 2020 [6] Chia-Yi Hou, "False positive and false negative coronavirus test results explained", thehill.com, May 07, 2020. [7] Myungsun Park, Joungha Won, Byung Yoon Choi & C. Justin Lee, "Optimization of primer sets and detection protocols for SARS-CoV-2 of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) using PCR and real-time PCR", Nature, 16 June 2020. [8] Kary B. Mullis et.al., "System for automated performance of the polymerase chain reaction", US Patent US5656493A. [9] "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Testing", ourworldindata.org. From which: According to criteria published by WHO in May, a positive rate of less than 5% is one indicator that the epidemic is under control in a country.

83 Vaccine Myths from docbastard.net

To all those who claim SARS-CoV-2—or any virus—does not exist: the virosphere consists of 7 realms

11 kingdoms, 22 phyla, 4 subphyla, 49 classes, 93 orders, 12 suborders, 368 families, 213 subfamilies, 3,769 genera, 86 subgenera, 16,215 species. Take that.

https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/

A summary of early parts of this series has appeared in the Dutch magazine Skepter 33(3), September 2020, as "Viruses don't exist" (covering Parts 1-5). German: Skeptiker (December 2020); English: Skeptic.org.uk (January 2021)

Comment Form is loading comments...

|